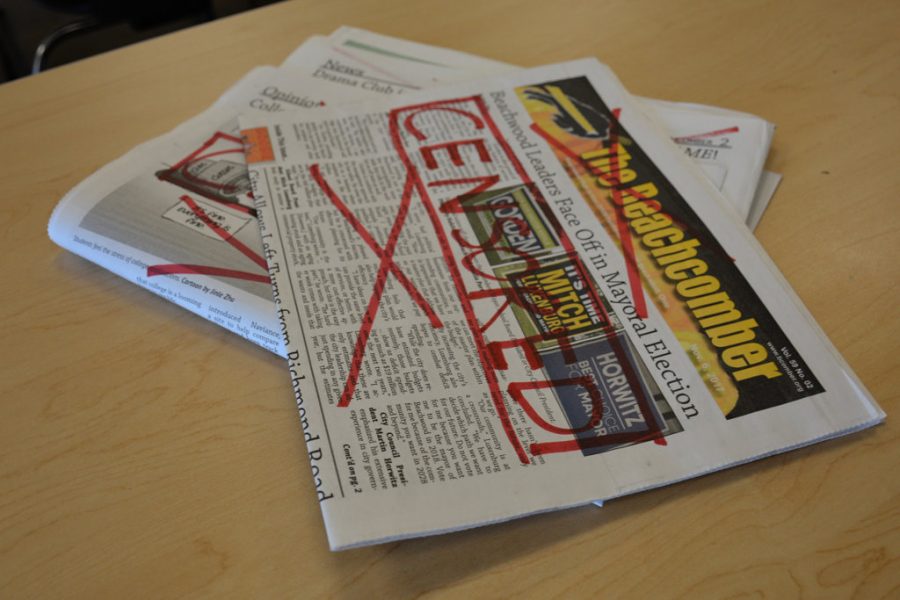

Beachcomber Subject to Censorship of Article in April Issue

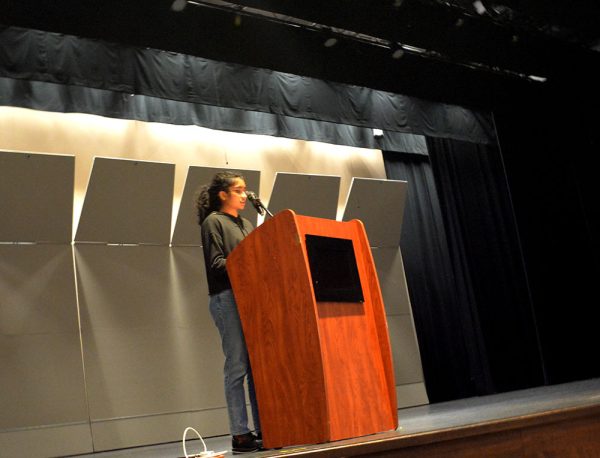

Five members of the Beachcomber staff met with Srithai, Superintendent Dr. Robert Hardis and the school district’s attorney Daniel McIntyre of Brindza McIntyre & Seed after school on April 9 in Davis’s classroom. In the meeting, it was clear that administrators would not allow the article to be published. Photo by Nakita Reidenbach.

School administrators censored an article submitted for publication in the April issue of the Beachcomber.

Principal Tony Srithai explained that administrators censored the story because they were concerned about the privacy of a student, although the student was not identified in the article.

“There was reason to believe that people could still be able to track down the student, and it could make that student uncomfortable or harassed, [therefore we should] protect that student,” he said.

Administrators have reviewed Beachcomber content prior to publication since 2006 and have expressed concerns about articles, but this is the first time that an article has been censored.

The School Board policy on student publications was revised in 2010 to read as follows:

“While students may address matters of interest or concern to their readers/viewers, as nonpublic forums, the style and content of the student publications and productions can be regulated for legitimate pedagogical, school-related reasons.”

Following established precedent, Beachcomber adviser Josh Davis shared the article with Principal Tony Srithai.

Soon after, Srithai informed Davis that administration would not allow the article to be published. After Davis informed the Beachcomber staff, they requested a meeting with administrators to attempt to resolve the issue.

The School Board policy on student publications was revised in 2010 to read as follows: ‘While students may address matters of interest or concern to their readers/viewers, as nonpublic forums, the style and content of the student publications and productions can be regulated for legitimate pedagogical, school-related reasons.’

Additionally, Beachcomber Editor-in-Chief Jinle Zhu contacted the Student Press Law Center (SPLC), an organization that advocates for First Amendment rights for student publications.

SPLC staff attorney Sommer Dean explained that the Supreme Court has put limits on student speech in school-sponsored publications.

“You are protected by the First Amendment,” Dean said. “However, there are instances where public high school administrators may censor student publications. This is a result of a case called Hazelwood v. Kuhlmeier.”

The SPLC’s page on censorship explains the Hazelwood case. In January 1988, the United States Supreme Court handed down its opinion in the case Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier. The Court upheld the decision of public high school administrators at Hazelwood East High School in a suburb of St. Louis, Mo., to censor stories concerning teen pregnancy and the effects of divorce on children. The stories had been published in a school-sponsored student newspaper.

The case distinguished between public forum and non-public forum publications. Factors that determine whether a publication is a public forum include whether it is part of the curriculum, whether it is sponsored by the school, and if there is a precedent of students making content decisions.

“If your newspaper is [not] a public forum and administrators can show that the censorship is related to a legitimate educational purposes, it will be allowed [by the courts],” Dean said.

When a publication is considered a public forum, the Supreme Court holds that administrators have to reach a higher bar in order to justify censorship, as established in the 1969 case of Tinker vs. Des Moines.

In 1965, Mary Beth and John Tinker, students in Des Moines, Iowa, were suspended from school for wearing black armbands in protest of the Vietnam War. The Supreme Court ultimately ruled that the students should not have been disciplined for their protest.

“It can hardly be argued that either students or teachers shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate,” Justice Abe Fortas wrote.

The ruling held that in order to justify censorship, administrators must show that the speech “creates a substantial disruption to the educational environment.”

Beachcomber staff members did not feel that the article would create such a disruption.

Five members of the Beachcomber staff met with Srithai, Superintendent Dr. Robert Hardis and the school district’s attorney Daniel McIntyre of Brindza McIntyre & Seed after school on April 9 in Davis’s classroom.

In the meeting, it was clear that administrators would not allow the article to be published.

The Beachcomber staff did not think this was fair.

“We as a staff went to the Ohio Scholastic Media Conference and attended a law and ethics forum,” Editor-in-Chief Jinle Zhu said. “What we learned there was inconsistent from what the school was telling us. We felt that their reasoning for censoring the article was completely unjustified.”

I also find it highly hypocritical that the administration is willing to stretch so far on a series of “could-bes” and “mights” to protect the comfort of a single student, but would be willing to censor the article and, in essence, create discomfort and take away the voices of the other students who were quoted in the article.

— Editor-in-Chief Jinle Zhu

“[I have been told that] justifications for censorship have to illustrate that the article would create a clear and substantial disruption and/or material interference,” Zhu explained in an email. “However, during our meeting with the administration, it became clear that they could NOT prove for certain that there would be any such thing. their explanations hinged on slippery slope fallacies and a chain of cause and effect that could only be supported with ‘well, this might happen.’”

“I also find it highly hypocritical that the administration is willing to stretch so far on a series of “could-bes” and “mights” to protect the comfort of a single student, but would be willing to censor the article and, in essence, create discomfort and take away the voices of the other students who were quoted in the article,” she added.

In Zhu’s view, the censorship runs counter to the larger mission of the school: to educate students.

“The Beachcomber has covered controversial issues in the past,” she said. “No matter how controversial the issue is, we have covered it because we believe students should know more about the school and their environment.”

“We do not understand how–when an article is censored–how students will know about the issue,” she said.