Prior Review and Student Censorship — Where’s the Line?

“Having my voice silenced, and seeing such an important event go undocumented, made me feel powerless and angry.”

During the past few years, The Beachcomber‘s coverage has come under increasing scrutiny, just as professional journalists have been increasingly attacked by politicians.

However, while the First Amendment may guarantee freedom of speech and freedom of the press, as a student publication that undergoes prior review, we are sometimes forced to give up that autonomy.

The struggle between student voices and school censorship is by no means a new battle; in fact, it is an issue that has been frequently debated throughout American history.

In 1969, students at Des Moines Independent Community School District wore black armbands to protest the war in Vietnam. The school district passed a preemptive ban on wearing the armbands and suspended the students, but the Supreme Court ruled in Tinker v. Des Moines on the side of the students.

“[Students do not] shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate,” the court wrote.

The Tinker standard, which developed from the case, stated that in order to censor student media, school administrators need to show that the publication would be disruptive to the learning environment.

Later, however, the court ruled in Bethel vs. Fraser (1986) that public school officials can prohibit student speech that is deemed “vulgar,” and ruled in Hazelwood vs. Kuhlmeier (1988) that the administration could censor student publications that are not public forums.

The Fraser and Hazelwood standards assert that administrators only need a reasonable educational justification in order to censor student work. What worries student journalists, particularly those writing for limited-closed forum publications, is the power given to school officials through these standards.

The censorship debate has continued recently as well. A federal district court determined in Dean vs. Utica (2004) that even under the Hazelwood standard, school administrators could not censor an article without reasonable justification, and Morse vs. Frederick (2007) determined the administration could censor student speech that promoted illegal activity. This constant back-and-forth has created many loopholes that administrators can use to silence student voices.

In the case of The Beachcomber, Superintendent Dr. Bob Hardis shared that censorship only occurs in two scenarios.

“[We would only censor] If information would violate the privacy rights or confidentiality of a student… [or] if there was reason to believe that the publishing of a piece would cause a disruption in the school environment,” he said.

“But if we believe that [a story] creates an unsafe environment or a disruptive learning environment, then I believe we, being administrators, have, not just the right to, but a responsibility to step in and censor that article, at least until it has been changed in some way,” he added.

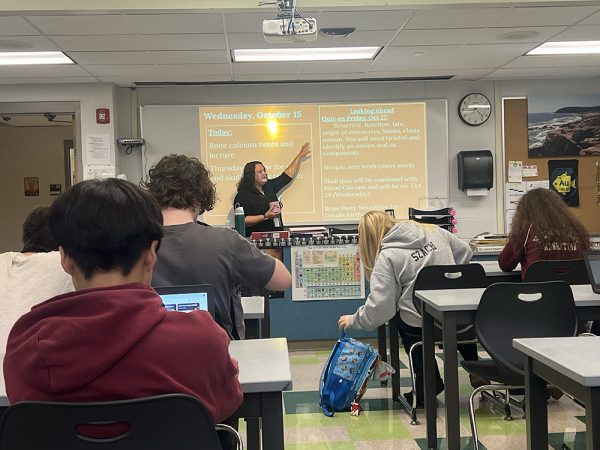

As someone who has been a member of The Beachcomber staff for three years, I’ve seen stories go through tedious editing and sometimes outright censorship. There have been several incidents where the administration expressed concerns about controversial stories, and Beachcomber editors had to meet with administrators and the school district attorney before the stories could be published.

For example, in my freshman year, one of my articles was censored a few days after submission. I had written about a student-organized protest that occurred weeks prior; however, because the protest was in response to another student’s alleged racist comments, I was unable to publish it due to “violation of privacy.” I never mentioned the student’s name or referred to them in the original article.

Having my voice silenced, and seeing such an important event go undocumented, made me feel powerless and angry. While I respect the administration’s desire to protect students, I often wonder who their decision protected: those marginalized or those in power?

Having only reported on the protest and its significance, I didn’t understand why I had to avoid writing about a crucial topic due to the minute possibility that a reader might identify a student from an event. It seemed like an excuse to ignore a crucial issue that needed to be discussed.

When I first had the idea to speak up about censorship, I wondered if this issue occurred in previous years. I spoke with former Editor-in-Chief, now professional journalist Catherine Perloff to discuss her experience on the 2011-2015 Beachcomber staff.

“Our principal, Ed Klein…wasn’t particularly heavy-handed,” she said. “There was obviously still prior review, and he did read the paper—sometimes [the administration would] make picky little changes or ask to read quotes beforehand—but I don’t think he outright censored anything.”

Perloff disclosed that the one article that even came close to censorship was one about a club field trip in which the students involved were caught in illegal activity.

“Right before [the article] went to press, the school board decided to develop this new policy to make the school disciplinary situation more rehabilitative than punitive,” Perloff said.

“I didn’t want my story to be the only thing putting these students’ names or this situation in print, so I changed the story and covered the policy change instead,” she continued.

Perloff also revealed that while certain teachers might have expressed concern about certain articles, once the paper was edited, she was never worried that it wouldn’t go to print. She explained that the 2011-2015 Beachcomber staff also covered controversial issues, but apart from interviewees asking to see quotes, there was no outright censorship.

“I’m very disappointed in the administration as an alum,” Perloff said. “If there are stories that people are sharing…[Censoring those stories is] not really fair to those people or to the larger community.”

Journalism is supposed to be an outlet for students to express their beliefs and expose problems within their community; without it, it becomes easier for the student voice to be washed away and ignored.

Now more than ever, in the midst of a worldwide pandemic, social media and online platforms have become virtually the only ways for students to communicate and raise awareness about certain issues.

To gather the legal perspective, I spoke with Student Press Law Center (SPLC) Staff Attorney Sommer Ingram Dean about the issues of prior review and censorship. She voiced her support for student journalists and their freedoms, as she used to be in the same position.

“I had the same situation when I was a student journalist, both in high school and college…our principal would have to read everything that we wrote before we published it,” Dean revealed.

Dean explained that while prior review isn’t illegal, prior restraint is. Prior restraint is when school officials prohibit the pursuit of a story before it’s even written.

“There is certainly a danger that still comes with prior review, because it gives school officials the opportunity to read what you’re covering before it actually goes to print, and it gives them the power to suggest or demand any changes to be made,” Dean added.

“That’s obviously a conflict of interest when, a lot of the time, the stories you’re writing about have to do with the administration, or have to do with the school as a whole, or maybe controversial things…that they don’t want to get out to the public,” Dean continued.

However, Dean clarified that administrators still need to have some reasonable justification in order to censor a story. She encourages students to reach out to the SPLC in case they think their story was censored unfairly.

Dean added that student journalists should still try to pursue stories they’re passionate about, even if it might cause a struggle with censorship.

“Just because your school is, or has been subject to prior review, doesn’t mean that you should shy away from looking into the hard stories, or looking into stories that you know the administration may not be thrilled with you writing,” Dean said.

Dean revealed in situations of censorship, contacting a legal team like the SPLC to argue the students’ cases can put pressure on administration and cause them to change their minds.

“Any time something like that happens, let us know…That’s also a great time to work with local news outlets or other people to still get the word out about what’s happening on your campus. That just sort of sends a message to these administrators, that you can try to silence us but we will find other ways to get the truth out,” Dean said.

Besides contacting the SPLC, student journalists who’ve had similar experiences with censorship have begun lobbying for the New Voices legislation.

The summer journalism workshop I attended at Indiana University included a module explaining what the New Voices movement was and encouraged students to support it.

As explained on the SPLC’s website, the New Voices movement is a “student-powered nonpartisan grassroots movement of state-based activists who seek to protect student press freedom with state laws.”

New Voices laws protect the First Amendment rights of student journalists, which as of early 2019 has been passed in California, Colorado, Illinois, Massachusetts and 10 other states.

I realize the issue of censorship doesn’t seem to affect Beachwood students outside The Beachcomber, but it’s actually a much bigger issue than it seems. As Perloff stated, censorship is unfair not only for reporters, but for the interviewees who took the time to share their stories, and for the entire community who might not be aware of issues that need to be covered.

Regardless, the student voice deserves to be heard and the student perspective deserves to be shared.

In 2009, Dr. Hardis, who was then BHS principal, commented to the Beachcomber about the censorship of a high school newspaper in Illinois.

“Media is our fourth estate,” Hardis said. “The newspaper is the voice of the students, whether it is pro-school or anti-school.”

Amy Chen began working for the Beachcomber in the spring of 2018. In addition to managing site design, she illustrates and covers a variety of topics in...

Yang began illustrating for the Beachcomber in the fall of 2019. In addition to this, he participates in the school's Academic Challenge and Science Olympiad...

Eric Marks • Oct 24, 2020 at 9:47 AM

Very impressive article, as an alum of the Beachcomber this makes me proud.

In ‘86 we had a member of the administration illegally parking everyday. We requested an interview with the administrator and were told that not only would this never be printed, that if we continued to pursue we would be disciplined. It was shameless and now almost 35 years later, I remember that more than any article I submitted.

Great work!