No Kings, No Queens, No More

The Snowball and Homecoming King and Queen don’t just appropriate the airs of monarchy, they do exactly what monarchs did for many countries—serve as an embodiment of the collective will and a projection of our power as a group.

“I beseech you, in the bowels of Christ, think it possible you may be mistaken.” – Oliver Cromwell, 1650

Every year, BHS crowns two royal couples: one presiding over the fall Homecoming festivities, the other over the January Snoball.

In years past, a Homecoming Queen was elected in a series of elimination elections, the first of which was a 12-way poll kicked off with a ‘Top 12’ assembly. The elected Queen would choose her date to the dance as de facto Homecoming King. While the Homecoming King status was not as official as that of the Queen, candidates for Homecoming Queen were ceremonially escorted to the Top 12 assembly by their male monarchical running mates.

For the positions of Snoball King and Queen, the procedure was more or less the same, but with the genders reversed: a King was elected, and that King chose his Queen. Many have criticized the heteronormativity of this practice, though perhaps the dearth of same-sex royal couples has less to do with systemic homophobia and more to do with the fact that every person elected to such a position has chosen to crown a member of the opposite sex as consort. Of course, the fact that every crowned monarch has chosen a hetero-passing running mate (even if the royal couple are just friends) is certainly indicative of a heteronormative bias among the student body.

Another, more prevalent claim, is that the Top 12 assembly may reinforce toxic ideals of popularity in high school.

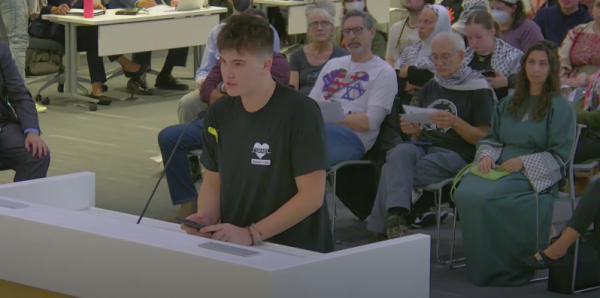

The 2019 Homecoming season was marked with a collective brouhaha over the election of the Queen, with some students calling for the abolition of the practice altogether. The BHS administration reached a compromise: the Top 12 would thereafter be called the “Homecoming Court”, and both King and Queen would be elected positions. Carly Petti and Antonio Roscoe were subsequently crowned.

Student Activities Director Craig Alexander explained the history of the tradition of Snoball King at BHS.

“Going back to when I just took over as Student Activities Coordinator, I was told that Snoball was supposed to be a ‘Sadie Hawkins Dance’,” he said. “That’s never actually been so since I took over.”

For the unbriefed, a ‘Sadie Hawkins Dance’ is an event to which girls are encouraged to bring boys. This is how the tradition of having only a Snoball King began.

“A few years ago there were a couple community members asking why we didn’t have a Homecoming King,” Alexander added.

This year, a survey was sent out to the student body and the changes were made.

I would argue that BHS has reached an important moment in its history; like the France of 1789 and the Russia of 1917, the time has come to shed our monarchy.

Many will argue that comparing BHS to revolutionary France and Russia is hyperbole. It is, but there is still an analogy to be made. In the United States, our view of monarchy is monochrome—monarchs are simply unpopular despots who oppose democracy. The Homecoming and Snowball monarchs are not really monarchs, say their apologists, they are elected positions that call themselves ‘King’ and ‘Queen’ in the spirit of tradition. This regressive view, molded by Jeffersonian-era propaganda, demonstrates a misunderstanding of what a monarch is. Kings and Queens were often populists, not tyrants, and were often elected positions for a significant time in history.

Having picked apart Palmer and Coulton’s A History of the Modern World (our school-issued European history textbook), I’ve found a consistent body of evidence (compiled for your entertainment)¹ indicating that the role of a monarch is cultural, not administrative, and usually viewed as a reflection of a popular, national character. Kings were very often elected, and almost always more popular than the institutions they shared the spotlight with.

“A lot of countries have royal families that serve a symbolic role, in terms of a country’s history, in terms of a country’s culture, in terms of a country’s traditions,” social studies teacher John Perse said. “In a state’s early history, Kings created some degree of focus and stability within the country as they consolidated.”

“Sometimes, coming out of feudal times, the King was just the [toughest guy] on the block,” he added. “The problem with getting rid of a King is that that King represents the country as a whole. That’s why so many countries still maintain that monarchical tradition.”

The Snoball and Homecoming King and Queen don’t just appropriate the airs of monarchy, they do exactly what monarchs did for many countries—serve as an embodiment of the collective will and a projection of our power as a group. Unlike student council, the King and Queen serve no administrative purpose. The fact that these monarchs don’t pass or overturn laws or send people to the chopping block doesn’t stop them from being figures of power, endorsed by the staff of BHS, over other students, in an attempt to empower the school. This was the role of a monarch in post-medieval Europe.

And yet, we, as denizens of the 21st century have the hindsight to say that though many European Kings were popular, elected, and often even just, they were Kings, and Kings are bad. Not because monarchy is inherently despotic but because the regalia of throne, altar and crown are supremacist and immoral. Telling others you are better than them, more deserving of power than them, is cruel and toxic. We are smart enough to realize this. While there is a case to be made for rewarding students for sports or academics, what can a student learn when BHS bestows a crown on the most popular couple? That they should take steps to become more popular?

High school culture is sometimes modeled on an ascending scale of popularity. This view of high school is today so ubiquitous in movies and TV that it can and should be relegated to a tired cliche. In fact, viewing high school as a simple hierarchy of popularity is pretty regressive. What about people who are only popular in certain circles? What about people who are popular among underclassmen but despised by seniors? The problem isn’t that this model is actually applicable to our BHS experience, the problem is that the election of the Homecoming and Snoball King can be easily interpreted as an endorsement of this simplistic, outdated model of human interaction. I would argue that there isn’t really a “popular crowd” at BHS, so why are we appropriating a manner of selecting one? And, of the many ways to do so, why is the method of selection tied to a heteronormative standard, with boys escorting girls to an assembly?

In the past few years, BHS has initiated several projects to improve the mental health of the student body: from a new SAY Counselor, to occasional visits from therapy dogs, to military personnel brought in to exercise with us, to collective mindfulness therapy. Consider instead what BHS would do if it was instead expedient to make students more self-conscious, more anxious and more miserable. Would they not sanction a literal popularity contest, put a literal crown on the most popular students, and parade them around the school?

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

1. Today, we often view Kings as feudal fixtures: the top rung of a rigid caste system embodied by the feudal manor. In reality, Kings, who limited the power of feudal personages over their vassals, were a buffer of absolute feudalism. In 911, German lords elected their first king, Conrad the Younger. The first French feudal King was Hugh Capet, who was elected by his vassals in 987. Capet’s descendants would rule as Kings of France until 1848. Both these kings traced their bloodlines back to Charlemagne, but Charlemagne was a polygamous, dubiously-Catholic clan chieftain (less Henry VIII, more Atilla the Hun). The monarchs of Bohemia and Poland-Lithuania were elected individually and repeatedly. The election of the first European Kings did not absolve them of the fact that they were, almost by definition, Kings.

Monarchy and feudalism did not work together, they battled for control over the populus. The rise of monarchical power in the 16th century, as with the Houses of Tudor, Valois, and Hapsburg coincided with the stagnation of the feudal system, the rise of the commercial middle class, the secularization of daily life during the Renaissance, and the relative weakness of Papal authority. Kings in this era were populists who, like Fernan II and Isabel I, appealed to religious zeal and antisemitism to gain power. In the 18th century, Louis XIV is reported to have proclaimed “L’État, c’est moi” (“I am the state”), marking the beginning of absolute divine right monarchy; the French were not taken aback by this statement, as the absolute power of the King indicated the might of the French people, not their subjugation.

Up until modern times, Kings have been populists who have enjoyed the support of their people, while their people consistently despised parliaments, feudal lords, and the landed gentry. When the English Parliament, in 1688, proclaimed the “Glorious Revolution” and deposed King James II, Catholics in Britain were so dedicated to their king that they launched a series of “Jacobian” revolts (from the Latin variant of James) to reinstall a powerful monarch who would protect their individual rights. In defiance of the partition of Poland, liberal Polish nationalists in the 18th century demanded more power for their elected King Stanislaw Poniatowski.

For the better part of the American Revolution, General Washington’s Continental Army raised toasts to King George III, who they saw as their protector against a despotic parliament. When, in 1830, the liberals of France became discontent with the ultra-conservative Charles X, the liberals, instead of simply removing the monarchy (as the Jacobins had in 1793), found a workable alternative in King Louis Philipe I, Charles’ liberal cousin.

Alice Soprunova (she/her) began writing for the Beachcomber in 2019. She covers stories pertaining to issues of social justice inside and outside BHS....

Claire began working for the Beachcomber in 2018. They cover layout. In addition to working for the Beachcomber, they play softball and does Destination...