What You Need to Know About COVID-19 Testing

CDC / Public Health Image Library

The omicron receptor-binding domain (RBD) and N-terminal domain (NTD) both have 15 and 11 mutations, respectively, which cause a significant reduction in plasma neutralizing activity in infected or vaccinated people, which means there is a significant reduction in antibodies to fight the virus.

Almost a year ago, the first cluster of Coronavirus cases was detected in Wuhan, China. Since then, over 50 million people have contracted the virus worldwide, and over 1.25 million people have died.

While early trials of a vaccine are promising, COVID-19 testing continues to be a critical tool for containing the virus.

“The more accurate the test, the better off we are in monitoring, treating and containing the virus,” Beachwood school nurse Kelly Debeljak said in a phone interview.

COVID-19 tests help to fight the virus in several ways. Individuals diagnosed with COVID-19 are able to self-quarantine and prevent transmission of the virus, as well as seek timely medical attention if necessary.

On a larger scale, tests give a sense of general infection trends that help epidemiologists monitor disease spread and recommend targeted, better-informed policies to reverse the proliferation of the virus.

Which is why it’s so crucial that tests are accurate.

Unfortunately, COVID-19 tests are of somewhat inconsistent accuracy, and can occasionally misdiagnose a COVID-infected person as healthy (false negative) or a noninfected person with COVID-19 (false positive).

A widely-circulated, high-profile example came to light Aug. 6, when the office of Ohio Governor Mike DeWine announced that the governor himself had tested positive for COVID-19 ahead of a meeting with President Donald Trump. However, a second and third test promptly showed that DeWine was in fact COVID-negative, and that the first had been a false positive.

False test results such as DeWine’s can occur due to one of any host of issues. Some, including cross-contamination of samples, improper storage methods, and inadequate sample-taking techniques, are the product of human error, but others seem more inherent to each of the three test types.

Viral tests, also known as PCR or molecular tests, diagnose active COVID infections by repeatedly copying, then identifying the genetic material of the virus in a process known as ‘amplification’.

While widely considered the most accurate test, and are even used to verify other tests, PCR samples collected too soon or too late may not contain enough genetic material to trigger a successful diagnosis, resulting in a false negative. False positives are much rarer.

Antigen tests are also diagnostic, but detect unique proteins on the surface of the COVID virus instead of its genetic material. Antigen tests are cheaper than viral tests, and since they yield results within minutes, they are often the go-to diagnosis method in most hospitals and clinics.

These advantages, however, come at a price: antigen tests are less sensitive than others, and are estimated to have a false negative frequency of anywhere between ten and 50 percent. Therefore, many doctors send symptomatic patients who tested negative with an antigen test to confirm their results with a secondary viral test. As with viral tests, false positives are uncommon but do occur.

Both diagnostic tests use the nasal or throat swab method to collect samples from patients.

Hannah Palovich, a current freshman at Laurel School, was tested at a drive-thru in Cleveland a month ago along with her aunt. Her test was done through a nasal swab.

“It made my nose burn and my eyes water, but overall it didn’t hurt that bad,” she said.

Palovich tested negative for COVID-19, and added that while the test “was very easy to access.”

Patients across the country have had similar experiences. Despite theoretically quick test administration and turnaround times, some wind up in hours-long lines, or receive their test results weeks after testing due to unprecedented demand and thrown-together public health strategies.

English teacher Josh Davis was tested at the University Hospitals Landerbrook drive-thru facility on Thursday, October 8. He was experiencing coughing and congestion.

“I don’t think my symptoms were that much in line with COVID, but I told [my doctor] that I was a teacher… and that we’re in-person, and [he wrote me an order for a test],” Davis said.

“First you wait in a line of cars, then you drive through a series of tents and they ask you to put your ID on the window so they can see who you are and get your information,” he recalled. Davis added that the technician used a nose swab in both nostrils.

“[The swab] kind of itches, and it kind of hurts, and it’s uncomfortable,” he added.

Like Palovich, Davis tested negative and received the results by phone approximately 24 hours after the test. He was not instructed to return if symptoms persisted.

Antibody tests are the least affected by the aforementioned challenges but also least useful. These identify antibodies produced by the immune system in response to COVID-19, and can diagnose past infections within a few weeks after the disease subsides.

While antibody tests supply data on the prevalence of COVID-19 and are used to verify the efficacy of potential vaccines, they are neither widely used nor widely available.

Antibody tests have relatively high occurrence of both false negatives and false positives, and are only used for very specific purposes. For example, individuals whose blood is found to have COVID antibodies are sought for convalescent plasma donations, which can help severely affected patients combat the disease.

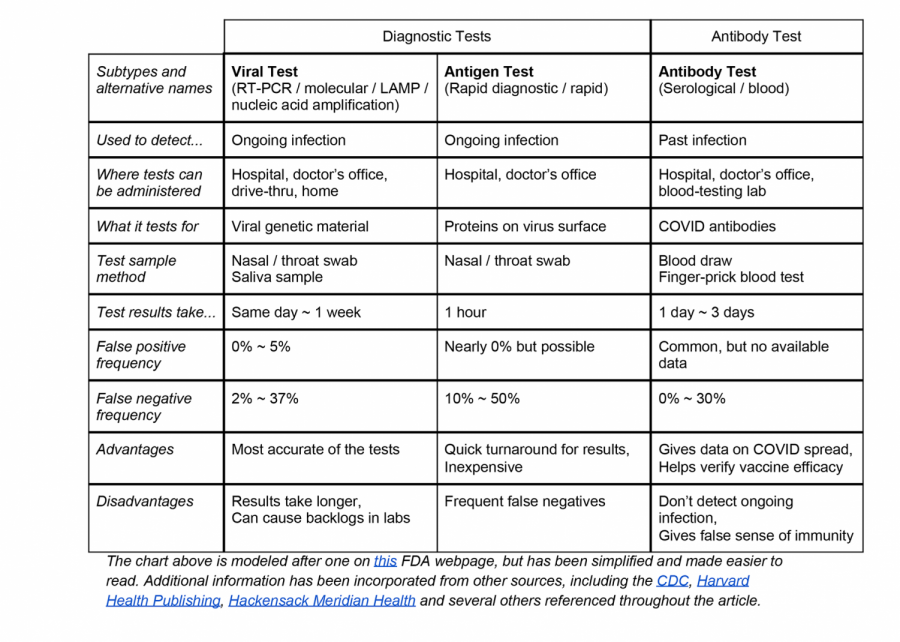

The chart below provides detailed information about each type of test.

DeWine’s false-positive resulted from an antigen test, according to an August 10 article on Harvard Health Publishing by senior faculty editor Robert H. Shmerling, MD.

“The recent experience of Ohio Governor Mike DeWine… [is] rare,” Shmerling noted, explaining that false positives in antigen tests are rare.

DeWine’s COVID-negative status was later ascertained by two PCR tests.

While it’s unclear how people have received false results to date, or even how large the scope of the problem is, the governor’s initial misdiagnosis was one of many. These incidents present a unique challenge in combatting the pandemic.

Nurse Debeljak oversees the BHS clinic, and she has prepared to deal with increased demand due to the pandemic.

“Students who are coming to take medication, students who have injuries, students who are having some emotional issues and need to talk, [can come to] the clinic,” she said.

She also explained that the school now has a room with an air filter system and routinely disinfected chairs where students with COVID-19 symptoms can go.

“Students will wait in the sick room to be picked up,” Debeljak said.

“If a student or staff member develops [COVID-19] symptoms,” she said, “they will go home and they will monitor themselves and contact their doctors. We will not be recommending or ordering people to get COVID testing; we will leave them to them and their primary care physician.”

Debeljak further explained that in any potential case of false positives or negatives, the school will defer to the judgement of doctors. For instance, a student or staff member who tests negative with an antigen test yet continues to exhibit COVID-19 symptoms may be asked by their doctor to take the more accurate viral test.

“Everybody’s so different with the way that they present. It’s going to be really individualized to that specific person,” she said.

~

This is a difficult time for everyone. Take care of yourself, prioritize your wellbeing, and never hesitate to reach out for help. Some helpful resources are included below:

Information about insurance, stimulus checks, evictions, food stamps, and more

Help with ongoing uncertainties

Other Questions about COVID-19 211 or 1-833-427-5634

CareLine Anxiety Hotline 1-800-720-9616

Disaster Distress Helpline 1-800-985-5990, or text ‘TalkWithUs’ (‘Hablanos’, for Spanish) to 66746

Crisis Text Line Text ‘CONNECT’ to 741741

National Suicide Prevention Lifeline 1-800-273-8255