After Three Years, Chromebook Program Gets Mixed Reviews

Beachwood implemented a one-to-one Chromebook program in the fall of 2013.

The program provided a Chromebook to every BMS and BHS student to use for schoolwork and allowed students who chose to use their own laptops.

According to Beachwood City Schools’ Director of Operations and Technology Dr. Ken Veon, the program was designed to improve student access to learning resources.

“We saw the need for technology in the classroom, so we felt instead of offering it just to use in school, we wanted the students to take it home because they can extend their learning at home,” Veon said.

After three years, laptops are now integrated into classrooms at BHS and BMS.

According to Veon, the initial cost of implementing the Chromebooks was $160,000 with an average yearly cost of $40,000 to $50,000 to maintain the program.

The program has also saved money on printing costs.

The Beachcomber anonymously surveyed 84 students and 10 staff members regarding their use of Chromebooks in the classrooms.

Nearly 65%, 55 of the 84 students surveyed, indicated that 1-3 classes require Chromebooks regularly, while 27%, 23 of the 84 respondents, indicated that 3-5 of their classes require Chromebooks.

While many students and staff have found the laptops to be advantageous, some concerns still linger.

Nearly all of the ten BHS teachers who responded to our anonymous online survey indicated that they use Chromebooks in their classrooms and found them useful for some activities.

“There are certainly several useful activities I use frequently that require the Chromebooks,” one teacher wrote. “…such as collective writing and sharing writing samples to look at and discuss on the board.”

“I feel that Chromebooks are helpful for readings and web-based work as well as extended formal typed writing and some group work,” another teacher responded.

Social studies teacher John Perse feels there are some benefits of the laptop program.

“I think laptops are very appropriate if kids are doing research,” Perse said. “I think laptops are also appropriate if [students] need to create a document or some kind of outline.”

On the other hand, Perse stated that laptops aren’t essential for his classwork, and he believes students taking notes with pen and paper tend to do better in his class. However, Perse acknowledged that some students do better with paper while others do better with typed notes.

A study published in April of 2014 by Pam A. Mueller of Princeton University and Daniel M. Oppenheimer of the University of California found results supporting Perse’s claims.

The study found that students retained less information when typing notes on a computer because they could type faster than when writing by hand, which meant they were focusing less on what they were actually writing down. Students using pen and paper were more likely to remember the content later.

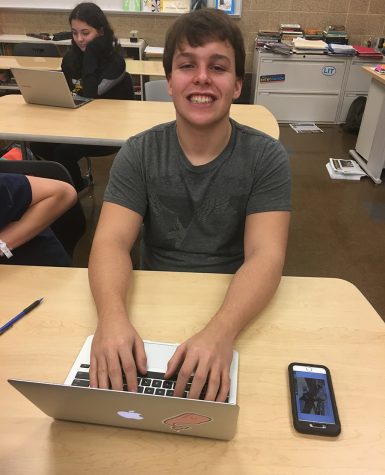

Freshman Connor Umpleby explained his preference.

“It really depends on the subject,” he said. “If it’s a lot of notes, then I use a laptop, but if it’s brief then I use paper.”

Umpleby went on to acknowledge that he may retain more when writing by hand, but still prefers the efficiency of taking notes on a laptop.

Another BHS freshman, Adam Charnas feels that typing notes on a laptop is more productive since spelling and grammatical errors are fixed right away. Charnas also agreed that he could take notes faster on a laptop.

Another study by Bjarte Furnes and Elisabeth Norman from the University of Bergen, Norway also found that retention is better for students reading paper instead of digital text. They conducted an experiment on 100 Norwegian college students comparing retention between print and digital text.

The students read material on a variety of print and digital platforms and then took a test. The study found that students who read on paper had higher test scores than students who read on computer screens.

One concern indicated by students in The Beachcomber survey was the Chromebooks’ lack of versatility.

“Chromebooks can’t run programs such as Photoshop, which I use for art,” one student responded.

85% of student survey respondents indicated they would rather use MacBooks than Chromebooks.

“I think [Chromebooks] are useful, but I would prefer a different type of laptop since they could do more. [Plus,] Google drive on my Chromebook is unreliable,” Umpleby said. Umpleby explained that his Google Drive sometimes has connectivity issues.

BMS English teacher Nate Smith uses Chromebooks in his classroom for applications such as WeVideo and Noodletools.

However, Smith also expressed a preference for some programs that are not available through the Google platform.

“Things seem to work smoother on Microsoft Word than Google Docs,” he said.

Both Umpleby and Charnas also prefer Microsoft Office to Google’s applications.

“Chromebooks are useful, but you can’t save any documents locally, and since teachers use Microsoft Word and PowerPoint; it’s hard to convert to Google Slides and Docs,” Charnas said.

However, Smith acknowledged that Chromebooks are more cost-effective than Macbooks.

Veon explained that many programs that can’t run on Chromebooks are available on Macbooks that can be checked out from the library.

For some, the critical question is whether laptops improve academic achievement.

Fethi A. Inan from Texas Tech University and colleagues from the University of Memphis evaluated 143 lessons that used laptops within certain classes at select schools in Maine in 2007. The results of the study were inconclusive. Of the seven schools that integrated laptops into the lessons, four had higher academic achievement, three schools had lower academic achievement and two schools were unaffected.

In the student survey, 79% of the respondents indicated that Chromebooks had not directly improved their academic performance.

Veon acknowledges that technology alone is not going to improve educational outcomes.

“It also [depends on] professional development for teachers,” Veon said. “[And] giving clear expectations to students. Things like that play into improvements in test scores, but we can’t say a student knows more because they use a Chromebook.”

Smith agrees that laptops alone don’t improve educational performance, but work ethic and effort will.

“I think if you’re a good student you’re going to get good grades, laptop or not,” Smith said.

Students seem to agree.

“They do not affect my education at all, as long as I try hard in school then I will get good grades,” BHS freshmen Connor said.

“I’ve seen no change in my grades since I’ve started using Chromebooks,” Charnas said.

The major concern for teachers is whether Chromebooks create a distraction for students in the classroom. Both Perse and Smith feel that they can be a distraction to students.

In fact, seven of the ten ten teacher respondents in our survey said they see Chromebooks as a distraction in their classes. Additionally, nine of the ten indicated that they feel that laptops decrease productivity of students in their classes.

Perse feels that the level of distraction depends on the maturity of the student.

“I know when I walk around, the students tend to be doing what they’re supposed to be doing,” Perse said. “[But] if I’m up at the front of the class delivering a lesson, then I’m not walking around, and at that point I don’t know whether they’re doing what they’re supposed to be doing.”

“I have some students who, when they are supposed to be discussing or reading something, are staring at their computer screen instead,” Smith said. “I had some students who did poorly as a direct result of the laptops, but at the same time [I feel] the laptops are necessary.”

Additionally, Smith said that monitoring what the class is doing on their computers is easier when the class is small. But when the class is large it is a lot more difficult to know what all the students are doing.

On the other hand, 85% of students in The Beachcomber’s survey did not feel that Chromebooks are distracting in class. Umpleby is one who feels that most students are able to resist the distraction.

“[Chromebooks] are only a distraction to people that play games in the back of the room,” he said. “They don’t affect my education, as long as I try hard [in school] I will get good grades regardless of computers.”

Veon feels that Chromebooks are of the same distractive nature as phones or passing notes, and that the educational value as well as the level of distraction can be controlled by a teacher who effectively monitors his or her class.

A study by Jian Li at the University of Maryland compared 21 Texas middle schools that received laptops and found positive results. Most students involved in one-on-one laptop programs were less likely to have disciplinary problems than students in schools without laptops.

The same study found students in one-to-one laptop programs showed some gains in mathematics, but did not show improvement in reading or other subjects.

One of the biggest concerns when the Chromebooks were first introduced was how kids without Internet at home would be able to do homework. This has turned out not to be a problem.

Veon surveyed 180 6th-11th graders in April 2016 regarding internet access at home. According to the survey 100% of respondents indicated they did have Internet access.

Veon points to efficiency as the main advantage of one-to-one laptops.

“What it does is it allows students to access information faster,” he said. “Think about how long it would take to go to the library and pull books that you can access and even articles from newspapers and magazines that you can access instantly on a computer.”

Tyler Pohlman has been writing for The Beachcomber since the fall of 2016. He has written several in-depth features and editorials about issues that affect...

![“My parents have always said that education is important. My parents are Chinese immigrants, I'm Chinese American, [and that's a] value that has always been ingrained in our community,” said Senior Lyndia Zheng, pictured with Tony Zheng](https://bcomber.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/DSC_4244-600x400.jpg)

K.D.N • Jan 2, 2019 at 12:33 PM

There was no mention of Windows PCs which work better than both Chromebooks and Macs while also being cost effective.