Five Facts and Five Figures

Commemorating Native American Heritage Month

Shawn Miller / Library of Congress

Joy Harjo is the first Native American Poet Laureate of the United States.

Fact: Native American tribes have independent sovereignty.

There are 566 recognized tribes in the U.S. that have sovereign governing powers. They have their own governments. Congress can pass laws that impact these tribes; however, the most common legislative action is to provide aid. Like states, they receive social services but not at an equitable level.

According to the Department of Indian Affairs, a person is legally recognized as Native American if they are an enrolled member of a tribe. In 2007, the Census Bureau estimated that 4.5 million people identified as Native Americans; however, only 1.98 million were enrolled members of tribes.

Figure: Vine Deloria Jr. (1933-2005)

Deloria belonged to the Standing Rock Sioux tribe. He went to a college preparatory school in South Dakota, then in the 1950’s, he joined the Marines and later went on to graduate from Iowa State. In 1962, he graduated Lutheran School of Theology with a Master’s degree in theology.

In 1964-1967, he was the executive director for the National Congress of American Indians. There he worked to revive the organization and to reform federal policies regarding Native Americans.

He earned a JD from the University of Colorado in 1970. He went on to teach at multiple universities in various positions.

He also wrote many books focused on Native American issues, and received a number of awards including the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Native Writer’s Circle of the Americas in 1992 and from the University of Colorado’s center for the American West. He received the Wallace Stegner Award in 2002 for his writing.

According to the New York Times, Deloria’s work was important in addressing misconceptions surrounding Native Americans and in bringing their perspectives to light.

Fact: The U.S. Constitution takes inspiration from Native American nations

As the founding fathers sought independence from Britain, they knew they would need a constitution to govern their new country. In order to find a long-lasting constitution that could balance the rights of different groups. They studied different governmental systems.

One of those they studied was that of the Iroquois Confederacy. The alliance of six Native nations had been governed for centuries by a constitution. It started when a leader of one of the nations addressed the colonies and urged them to unite. In fact, the Iroquois Confederacy is the oldest living participatory democracy, according to PBS.

Benjamin Franklin was inspired by the unity and harmony that the Iroquois had achieved. At the Albany Congress, which was attended by both colonists and the Iroquois, he used the six Nations as a reference for the new colonies’ constitution. He even invited the Iroquois leaders to the Continental Congress.

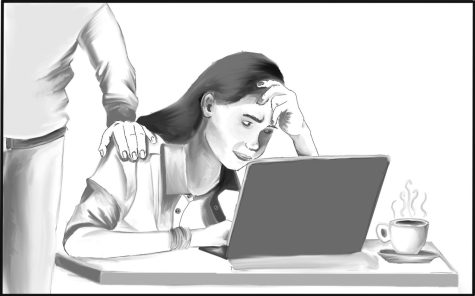

Figure: Joy Harjo (1951-)

Born Joy Foster, Harjo belongs to the Muscogee Creek Nation. Her father was Creek, and her mother part Cherokee, Irish and French. She grew up with an abusive father and step-father.

Her grandmother played saxophone, her mother sang and her aunt was an artist. With her history of abuse, she struggled to talk to others, and the creative role models in her life inspired her to express herself through art.

She was just 16 when her stepfather made her leave the house, so she enrolled at the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

When Harjo was at the school in the late 1960s, she participated in the ‘renaissance of contemporary native art,’ according to Women’s History. She participated in all-Native drama and dance groups and wrote songs for a Native rock band.

Harjo was married as a teenager, had a child, and then got divorced. When she was nineteen, she became a full-fledged member of the Muscogee branch of her tribe and changed her name to Joy Harjo, named after her grandmother.

She went to study pre-med at the University of New Mexico, but later changed her major to art and then to creative writing, since she was inspired by Native American poets.

She had another child with poet Simon J. Ortiz, and when she was 22 she started writing. The next year, she graduated and went to a writing workshop at Iowa State. In 1978, she started teaching at a number of universities.

Harjo has received many awards for her poems, including a PEN USA Literary Award and the Ruth Lily Prize for Lifetime Achievement from the Poetry Foundation. She is the chancellor of the Academy of American Poets. She also founded the Native Arts and Cultures Foundation.

She is the current U.S. poet laureate, the first Native American to hold that position and the second ever to serve three terms.

One of her projects is making a database of stories of the Native American poets.

“‘You will not find us fairly represented, if at all, in the cultural storytelling of America, and nearly nonexistent in the American book of poetry,” she told PBS Newshour.

Fact: Many Indigenous people oppose Mt. Rushmore

While Mt. Rushmore may seem like a harmless tribute to prominent American presidents, there’s more to it. The land on which the monument sits was stolen from Native Americans.

It was a part of the Lakota reservation and protected by the Treaty of Fort Laramie; however, when gold was found, white prospectors moved in and the land was forcefully taken in 1877.

Sculptor Gutzon Borglum oversaw the carving of the 60-ft faces in the granite cliffs during the period of 1927-41.

On Aug. 29, 1970, protesters gathered at the mountain. They demanded the return of the land and the honoring of the broken treaty. Several protesters climbed up the mountain; however, the protest fell on deaf ears and 20 people were arrested.

A 1980 Supreme Court decision offered the tribe $105 million for their troubles. However, the Lakota rejected the money and continued to demand their land back.

Figure: John Herrington (1958-)

John Herrington of the Chickasaw tribe became the first Native American astronaut when he flew on the Space Shuttle Endeavour in 2002.

As a child, his family moved 14 times in Oklahoma, Wyoming, Colorado and Texas. He went to college but struggled, so he took a break and left for the mountains where he worked on a survey team.

There, he discovered he had a strength in real life math, so he returned and received a degree in applied math at University of Colorado at Colorado Springs in 1983, according to the American Indian Education Fund.

He joined the Navy and became a Naval Aviator in 1985 after attending Aviation Officer Candidate School. Ten years later, he earned his Master’s degree in aeronautical engineering from the U.S. Naval Postgraduate School.

According to the Chickasaw Hall of Fame, in 1998, after two years of training with NASA at the Johnson Space Center, he became a mission specialist for flight assignments. In 2002, he joined the crew of the Endeavour and became the first Native American to walk in space as well as the first member of a tribe to fly in space.

According to NASA, he brought the flag of his tribe with him into space as well as other items, such as a traditional flute, honouring his heritage.

Afterwards, he became a public speaker, encouraging students in their pursuit of education.

Fact: Assimilation was forced on Native American children

Beginning with the Indian Civilization Act Fund in 1819, the U.S. Federal Government collaborated with various Christian churches to establish boarding schools intended to assimilate Native children and thereby destroy their cultures.

“Kill the Indian and save the man,” said General Richard Henry Pratt, who founded the Carlisle Indian School.

Children who attended the boarding schools weren’t allowed to speak their native tongues, or they’d face punishment, which included withholding food, physical harm and isolation.

By 1920, over 50,000 Native children attended Indian boarding schools.

They had to change their names to white names, were taught Eurocentric history and were forced to convert to Christianity. Many schools were isolated from reservations in order to completely remove the children from Native cultural influences, according to Northern Plains Reservation Aid.

If tribes resisted, the tribe would be faced with a blockage of food and supplies. In many cases, they were met with force where officers would go in and take the children regardless of the tribe’s decision. Children were torn from their families.

In 1978, Native parents finally got the right to refuse sending their children away to the cruel boarding schools, due to the Indian Child Welfare Act.

Figure: Susan La Flesche (1865-1915)

Susan La Flesche was a multilingual Native American who graduated as salutatorian at Hampton University with musical and artistic abilities, defying all expectations people had of her.

She was driven by the words of her father, Chief Joseph La Flesche of the Omaha tribe in Nebraska:

“Do you always want to be simply called ‘those Indians,’ or do you want to go to school and be somebody in the world?’”

Chief La Flesche pushed for assimilation into the white culture, for fears of extinction by the hands of the majority. This caused a divide in the tribe between those who wanted to protect their culture and those who wanted to protect their future. In order to strive for a better future for her people but also preserve their culture, she learnt about the outside world but kept her own culture close at heart. An example of this is her learning new languages but still knowing her own.

La Flesche dreamed of becoming a doctor after witnessing a horrific scene when she was young. A Native American woman was dying, but even though a doctor was called multiple times, no one ever came and the woman died. La Flesche was shocked by the apathy of white doctors towards indigenous people, and so she became a doctor herself, hoping to prevent such tragedies from continuing.

After graduating from Hampton, she went to Women’s Medical College of Pennsylvania and graduated at the top of her class. She was among the first female doctors in the nation and the first Native American doctor, but she wasn’t allowed to vote; she didn’t even count as a citizen in the eyes of the government.

She went back to her tribe and took care of all the patients, in fact her white counterpart quit when so many people came specifically asking for La Flesche to treat them. She wasn’t just a doctor, but also an advisor and teacher. She not only took care of their health but worked to maintain their quality of life. She rallied against alcohol abuse while she struggled with her own husband’s alcoholism.

According to the National Park Service, in 1913, she built a hospital for her tribe, financed through donations. Two years later, she died. The hospital, named Dr. Susan La Flesche Picotte Memorial Hospital, still stands today, serving the people La Flesche cared so deeply for.

Fact: Indigenous people used Aspirin

Long before the painkiller Aspirin became commercially used and industrially produced, it was consumed by indigenous people.

Aspirin contains salicylic acid, an ingredient found in the bark of willow trees. Native Americans would chew tree bark or boil its leaves to treat pains such as toothaches and headaches, according to Native Tech.

Figure: Wilma Mankiller (1945-2010)

Wilma Mankiller is of Cherokee descent. Her last name is passed down from an ancestor who achieved recognition as a warrior.

Mankiller was born in Oklahoma but she and her family were moved by the government to San Francisco in hopes of assimilating the indigenous community into an urban environment.

She went to college in California and then became a social worker. She married and had children, but the marriage was hard.

In 1969, despite her husband’s wishes for her to be a stereotypical housewife, she became an activist and was involved in the Native American occupation of Alcatraz.

She divorced her husband, and, with her children, moved back to her home town of Tahlequah, Oklahoma in 1974.

However, in 1976, she was in a car accident which killed her friend who was in the car with her. Just a year later, she was diagnosed with myasthenia gravis, a neuromuscular disease which made it difficult to accomplish everyday tasks. Nevertheless, she did not allow herself to be defined by her challenges .

“We’ve had daunting problems in many critical areas, but I believe in the old Cherokee injunction to ‘be of a good mind’,” she told the National Women’s Hall of Fame when she was inducted in 1993. “Today it’s called positive thinking.”

She worked to improve the conditions in the village of Bell, Oklahoma on the Cherokee reservation. Using federal grants, she provided the village with safer housing and a reliable water supply. Her actions garnered national attention, and in 1987, she was named Ms Magazine Woman of the Year. While working on this project she also met her future spouse, Charlie Soap.

In 1983 she became Deputy Principal Chief and then became Principal Chief two years later after the former Principal Chief left to become the head of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. When she ran for the position two years later, she won. Furthermore, she gained 82% support from voters in 1992.

Her actions as Principal Chief were directed for education, health and employment and they were successful. Her administration lowered the rate of infant mortality and doubled employment rates. She founded the Institute for Cherokee Literacy and provided money for Head Start and the Cherokee Home Health Agency.

Her administration came to an end in 1995 after she decided not to run again due to her diagnosis of lymphoma. She died of this cancer in 2010, but not before receiving the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1998.

“‘I want to be remembered as the person who helped us restore faith in ourselves,’ she once said,” according to Time Magazine, which named her one of the 100 Women of the Year for 1985.

Hiba Z. Ali began writing for the Beachcomber in fall of 2019. She covers diversity in the school. In addition to writing for the Beachcomber, she also...