Innoculate Yourself Against Senioritis

“We have observed a significant inflammation of the symptoms of senioritis as a result of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.”

Senioritis is an acquired illness observed most commonly in high school seniors. It is characterized as a telltale ennui stemming from a crisis of purpose associated with the sudden evaporation of clear, concrete goals (upon acceptance to college) or of incentives to dedicate oneself to one’s schoolwork (following the beginning of a second semester, in which grades are markedly less relevant to college acceptance).

Symptoms of senioritis include: waking up at 8 AM and spending ten minutes staring at the ceiling asking yourself if there is any point to getting up, not showering for extended periods, letting dozens of emails pile up in your inbox, going to bed without doing the homework due the following day, a significant slip in quarterly grade-point average, habitually arriving late to Zoom meetings and/or physical classes without a care in the world.

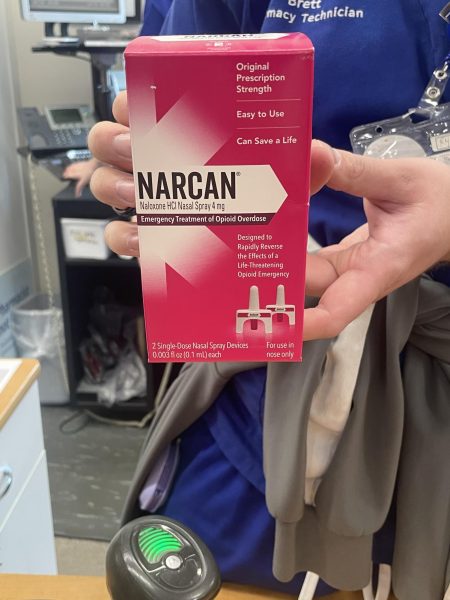

We have observed a significant inflammation of the symptoms of senioritis as a result of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. However, this exacerbation occurs independently of whether or not a patient has actually tested positive — meaning that the flare-up is, rather than a result of contracting coronavirus and senioritis simultaneously, a reaction to the community disruptions caused by the pandemic and the resulting social distancing efforts. This conclusion was reached because, according to the most recent research, there is no viral or bacterial infection that causes senioritis.

With the diminishing returns of the circuit through high school classes, it is unsurprising that a hybrid school model, undertaken in the name of public health, turns senior year into even more of a waste of time. Likewise, it becomes easier to not come to class, not pay attention, take long naps, and partake in all the traditional activities associated with senioritis when class has, at least half the time, all the social and administrative weight of a FaceTime call.

However, the situation is not irrecoverable, as there are a number of precautions one can take to prevent contracting senioritis, easing its symptoms, or (with luck) curing the illness.

Pre-senioritis high school is a plane of existence occupied with, and, in a very real way, defined by concrete goals. The student strives to get a specific integer-score on the ACT, score high enough on that essay due the following week to maintain one’s current letter grade, procure a satisfactory AP test score, et cetera.

One of the causes of senioritis is the sudden dissipation of these sorts of concrete goals. Grade point averages, ACT scores and AP scores simply no longer matter — and the experience of losing the mathematical structure they provide can be disillusioning.

It is not enough to simply occupy oneself with new concrete goals, because whatever new goal you come up with (beating a sports-related personal record, maintaining your GPA in the face of senioritis) no longer carry the same perceived life-or-death weight in college admissions.

For this reason, a healthy approach would be to altogether reject the notion of the concrete goal, and instead invest time into abstract goals that still carry the weight of something like your junior year ACT score. These goals are harder to formulate and probe, but the added difficulty can be helpful in restoring the sense of purpose in whose absence senioritis festers.

If you are a “gifted kid” weary of college burnout, perhaps your abstract goal could be to work on note-taking and studying skills that will become critical in college, which comparatively easier high school classes have left you ill-prepared for. Perhaps you would like to take this time to become healthier, whether through physical exercise or through reconsideration of diet. Perhaps you have abstract mental health goals that have gone unrealized throughout high school.

The most obvious abstract goal may be to begin learning for the sake of learning, instead of learning for the grade. That sort of advice sounds saccharine and useless in an environment where every score matters, but, when scores no longer matter, it becomes more genuine and realizable.

Apart from recontextualizing your goals, there are also many things a graduating senior can do to occupy themselves in preparation for college. If you have committed to a school, chances are there are ways for you to easily reach out to other incoming first-years. If you are still weighing your choices, or are waiting to hear back from several schools, why not cast a wide net and chat with people across the board?

Likewise, what offerings does your future (or prospective) university have in terms of extracurricular activities? Have you fully explored the various majors and minors offered by the school? If so, have you looked at the actual classes you have to take? All of this information is readily available on-line, as are, in some universities, model classes. Recent public health emergencies have seriously complicated many aspects of the application process, but have also aided in the proliferation of online programming for prospective students.

Now is also a good time to educate yourself about things that you haven’t learned in school. Do you know how your family’s health insurance works, and when you will stop being eligible for it? Does your university have a health insurance plan you can pay into, and is it worth it for you to switch to it from your parents’?

If you plan on being sexually active in college, have you weighed all the contraceptive options open to you? Do you know how to buy a morning-after pill? Have you been exposed to the films, art and literature that is part of the popular culture of our age (and ergo of your future college), or do you need to finally sit down and watch Citizen Kane or find out the difference between expressionism and impressionism?

Regardless of specifics, senioritis brings a classical and universal problem to the forefront of one’s psyche. Finding purpose in an otherwise purposeless existence is, after all, the common thread between everything from the “noble truths” of Buddhism to the appeal of fascist ideologies to the origin of concepts such as fate.

Conveniently, high school students have been freed from this struggle — their purpose is high school — grades, scores, studying, all. But being forced to find one’s own purpose is as common to senior year as it is fundamental to that which we are on the precipice of — adulthood.

Alice Soprunova (she/her) began writing for the Beachcomber in 2019. She covers stories pertaining to issues of social justice inside and outside BHS....