When Being Biracial Isn’t the Best of Both Worlds

“I belong to a race that has never belonged to either world; we were viewed as savage on the one hand and power-hungry on the other.”

When I was seven years old, attending a sports camp, a white boy in my grade apparently noticed that one day a black woman picked me up, and another day, a white man.

While I knew the difference between black and white, my parents never prepared me for the day that boy would call me a crossbreed, another term for a mutt– like I was something that belonged to the wild, not in human life.

How could any parent ever really prepare their young child for the feelings of confusion and embarrassment that evolve once they realize they are inherently disadvantaged because of their skin color?

That little boy at camp spurred an identity crisis in my brain, and from that day on I would wonder why there was no opportunity to check multiple boxes on important documents such as both “African American/black” and “Caucasian/white.”

For many years, because of those boxes on official forms, I mistakenly thought I had to belong to one or the other. I was too white for the black kids, and too black for the white kids– the white kids code switched when I code switched, and around my African American peers, I was told that I “talked white.”

I struggled to figure out where I belonged, since the world simply did not want me to be “mixed” in any way. I felt like I had to be 60/40 or 80/20 depending on the time and place.

The more cognisant I became of the world I lived in, I found that blacks were disproportionately targeted by police, and I wanted to side with them– because had it come down to me being in the car with a bunch of white friends, I felt that I would have most likely suffered punishment.

However, I would often feel socially excluded by black peers due to my mixed heritage, making me feel like I could not embrace that side of me. I began to feel that the only tie I had to my blackness was my skin color.

Take choir class, for example, in middle school. The black kids took the last row of seats in the choir room every day, while students of other races took the rows closer to the instructor. Since we could sit where we wanted, one day I asked some of the black kids if I could sit next to them.

A boy in the back row quickly responded, “Just go sit with your white friends.”

Since nobody disagreed with him, that statement was all I needed to feel rejected by the black students in my grade.

While growing up, many people told me that I had the “best of both worlds” being mixed.

Thinking I was the only one, somewhat ashamed of my identity crisis, I recently opened up to a friend about my experiences as a half-black and half-Ashkenazi Jewish female, and as it turned out, they were of the same ethnic backgrounds.

There was even a name for the adolescent crisis I was having.

“It’s called a tragic mulatto,” they said– and their words have resonated with me ever since.

A social disease like no other, symptoms of Tragic Mulatto Syndrome may include but are not limited to: being awkwardly asked your ethnicity, via i.e. “What are you?”; being asked if you are adopted; being mistaken for a different ethnicity, commonly Latino, which occurs when a pedestrian walks up to you speaking Spanish. Other symptoms include feeling pressure to be one or the other, and an embarrassment to embrace both cultures in all aspects of one’s life.

The word ‘mulatto’ formally describes a person of European and African lineage, or an offspring of a black and white person. The word is derived from the Spanish and Portuguese word “mulato,” which formally translates to “of mixed breed,” stemming from the root “mulo” or mules. The word ‘mulatto’ possesses a tangled history, as the first mulattos in North America were the product of rape between master and slave.

According to research compiled by the Jim Crow Museum at Ferris State University, “The mulatto woman was depicted as a seductress whose beauty drove white men to rape her… One slaver noted, ‘There is not a likely looking girl in this State that is not the concubine of a white man.’”

The beginning of mulatto culture, after all, was tragic to begin with. Although white men found pleasure in raping black women, they saw a problem in the result of that rape: biracial offspring who could have a potential higher social status and blur the lines between the races.

These fears were addressed by the evolving belief, codified into law, that any black lineage made someone fully black– and to be black meant to be a slave– thus problem “solved.”

According to the Jim Crow Museum at FSU, interracial rape and white supremacist laws worked together to enforce racial hierarchies.

“By prohibiting racial intermarriage, winking at interracial sex, and defining all mixed offspring as black,” purebred white superiority was achieved while simulataneously fetishizing and preying on black women.

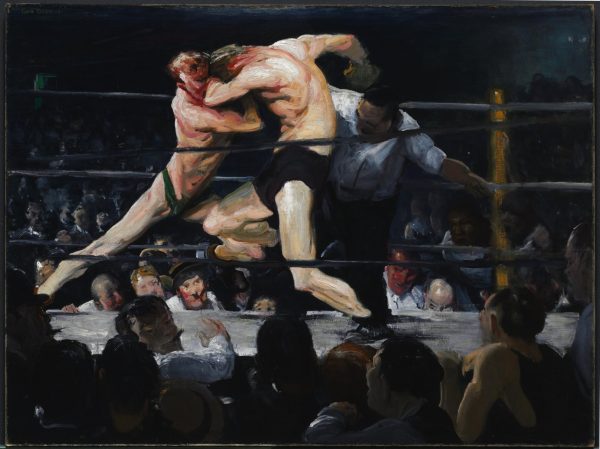

Even following the post-Reconstruction era, the mixed race hit another tragic wall as George M. Fredrickson described in a historical analysis entitled The Black Image in the White Mind (1982) suggesting a historical ideology believing that mulattos were a corrupt, degenerate race because of their white lineage, which made them hungry for power and ambitious, and their shared black lineage made them savage and in all ways improper. This view was widely shared by many Americans in the 19th century, reestablished in the film Birth of a Nation in 1915.

It came as no surprise to me that biracials were classified as a “degenerate” race, since mixed people of earlier centuries were commonly a product of a rape that was never considered a crime.

I figure it was destined for me not to feel fully immersed into one race or the other, given the perception that any black blood made one fully black yet white blood made one too rambunctious.

Despite the image of biracials as power-hungry yet savage, and even sex symbols, they rose to a prestigious position with an “artisocracy of color,” fiercely dividing the black race in early 20th century America, as described by The Colored American Magazine.

The brown paper bag test and the “ruler” test were of common use in the early 1900s by blacks to discriminate against other blacks, the beginning of an era where we, African American people, turned blind eye to colorism, which had its origins in slave owners favoring fairer-skinned slaves for domestic chores while their darker-toned counterparts were stationed working brutal hours in the hot, southern sun.

Recognized as people of color, black and white biracial individuals found themselves in a class between the wealthy whites and enslaved blacks, as in the 17th and 18th centuries, slave owners were known to have treated their mixed offspring like children, offering them more opportunity than the slave children on plantations.

In French Haiti, a French colonist, Moreau de St. Mery, produced a scale represeting nine degrees of color, indicated that the last classification closest to complete white lineage on the scale was accepted as white, but a person was not accepted as white if they had more than 1/64 African descent.

The farther one was from being 100% black on his genealogical scale, the less harsh prejudice the individual was subjected to by whites, but the less solidarity one shared with other black people.

I felt this when I got called an “uppity negro” by a group of black kids at a convention in Detroit, Michigan, where we were supposed to be coming together in black solidarity.

The term “uppity negro,” nowadays is a full-fledged joke among many black adolescents, but the phrase “uppity negro,” with “uppity” meaning arrogant, was initially directed at the mulatto race.

I attribute much of the struggles that I endured as a pre-teen to the historical damage left by the legacy of the brown paper bag test. If one’s skin was darker than a brown paper bag, they were not included in a multitude of black institutions or various black communities.

I find it hard to embrace my identity, for had I lived in the 19th century, all I would have been was a sex symbol, a result of a rape by a white man, not true love between two parents of different ethnicities.

Rather than the best of both worlds, I have come to identify my experience with the best of three: my people are the black people, who have endured brutal racism and discriminatory violence, set in a trap created by white superiority for centuries; my people, my other people, are considered white; and my people are also the biracial people, who have their own unique history.

I belong to a race that has never belonged to either world; we were viewed as savage on the one hand and power-hungry on the other. I have come to question which people really were the savages and the power-hungry monsters. The more I learn of my history, the more I understand that the true monsters were white men who controlled the law and should have been punishing rapists, but were too busy committing the act of rape themselves.

I find it hard to be proud of both sides of my family tree, seeing that there are times when I feel like my own father could never understand the struggle of being brown-skinned, and though he sympathized and was vocally opposed to discrimination of any sort, I know he will always be treated better than I will.

It is hard having one parent who reaps the benefits of white privilege, though he acknowledges his privilege and uses it for the better, and having a parent who is doubly oppressed as an African-American woman.

Though my mother has taught me about the hardships black women have endured, and taught me the grit with which I must pursue my goals, and the history of the oppression of black people by whites, my takeaway from history textbooks has been that the white man has historically been the enemy of blacks in America. I have felt my perception of the world beginning to swallow my white father into the generalization of the white-male enemy, just because of his skin.

My biracial experience has tested my ability to perceive people not with the gruesome racial stereotypes that they have been subjected to, but with the mentality that they are human and should be treated with kindness until they show me a reason to do otherwise.

While much of my identity crisis was a result of a historical and cultural clash, there are many moments when growing up biracial has simply been awkward.

As a young girl, I attended Camp Wise, a primarily white, Jewish camp near Burton, Ohio. We travelled to water parks. I walked by myself to get food, and counselors from another camp, which brought many African American children to the park, tried to take me back with them.

When I was recently on vacation with my Ashkenazi family, entering a prestigious art museum, a museum worker closed off the line after my cousins were admitted, and I was left behind. Eventually I made my way to them after convincing the guards that they were my family–– but that’s not the point.

Each of these incidents were symptoms of my condition: the Tragic Mulatto Syndrome. The worst part is–and any other biracial children will understand this–that you have to find the cure on your own.

As biracial people, we must learn to find peace in the histories of the different cultures we are part of. We must acknowledge that although there is cultural harmony inside the home, outside of the home the mixed child will contract their own, individualized symptoms of Tragic Mulatto Syndrome and struggle to define their identity.

The internal struggle is all part of figuring it out, but each of our unique experiences will ultimately define the way we choose to embrace our identity.

Not every mixed boy or girl may close their identity crisis standing 50/50, feeling half and half– given that we are bound by the ropes of white privilege and colorism– but in discovering who we are, as biracial individuals, we must first understand our history and choose how to act upon the past.

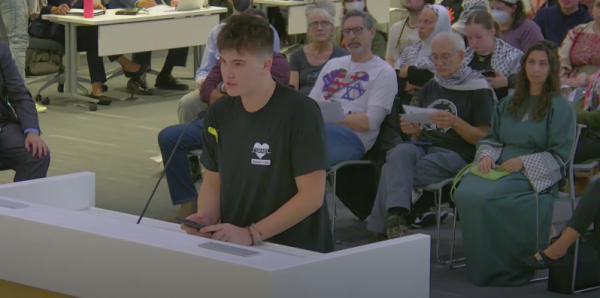

Elizabeth Metz began writing for the Beachcomber in 2018. She enjoys covering identity politics and sports. In addition to writing for the Beachcomber,...

Yang began illustrating for the Beachcomber in the fall of 2019. In addition to this, he participates in the school's Academic Challenge and Science Olympiad...

Professor Carrie Hall • Oct 20, 2021 at 1:30 AM

I’m a bi-racial female, and oh my, I could really relate to this article. I’m in the second year of my Ph.D. program straight A’s. It’s been a struggle for me here in the prejudiced state of Oklahoma. Thanks for posting this article, it should be a part of Black History month in every school. As a professor, I will be sharing it with my students.

Dakota • Jun 22, 2020 at 8:46 AM

This article should be mandatory reading in every school on either MLK day or during Black History month. Covers so many areas that are silenced in the mainstream media where biracial (black/white) people are projected as a one race identity, which is not for the sake, health or even benefit of biracial people. Many like myself have also perceived the “[…] perception of the world beginning to swallow my white father into the generalization of the white-male enemy, just because of his skin”, which is just as painful, if not more in some ways, as the racism toward the other side, especially for those of us whose lives have been intimately shaped by nurturing and sensitive people who are white, and who have mostly been the ones to just see us as humans (not black or white), but would also not even harm a fly.

I also personally feel a lot of resentment surrounding the automatic and extremely overbearing and gregarious assignment of “black” in America just because you are half (or less, technically, in that African-Americans are generally at least 10% white). I feel this is done mainly to try to boost up the prestige of black people, but which is at the full expense of allowing a human being to fully be who they are, and to find inner harmony between two opposite worlds and people.

Forcing biracial people to choose one side is not ethical. What’s more is that, biracial and mixed people in the black community create tremendous insecurities and an inferiority complex within people who are actually black (75% or more of DNA from Africa), which is not fair to them and undermines the value of authentic African traits and features, and which leads to resentments and hostility toward biracial and mixed people, from black people, which further exasperates what can be an already tough identity situation for a biracial person in a racially divided world. The media and others who are clinging to the outdated one drop rule should really consider that before assigning a single race to a mixed person, especially a mixed person of European and African decent, but this is truly applicable I believe to all mixed people, who just need to be allowed to be human first and both.

For purposes of clarification, I am biracial, Irish/white and African-American.

Margaret Cleton • Feb 3, 2020 at 3:43 PM

Thank you for sharing your personal, heartfelt, and informed story. As a product of colonialism, (Dutch/Indonesian) my experience is slightly different, but I feel similarities and kinship with your experience. My mother to this day, and she is 91, still thinks herself as ugly because her mother, who had a Dutch father and Indonesian mother, felt the sting of institutionalized racism that kept the colonial order. My grandmother favored her lighter colored children; my mother, being dark, felt the slight. And we also have the word “mulatto” – and I had no idea that it derives from “mule.” I would like to say that I am the best of both worlds, white and “colored.” But in fact, I feel a deep rooted resentment towards the Dutch part. And, like you, I am not one or the other, but a third identity. Luckily, I think the world is changing, and this “third” is becoming ever more ubiquitous.

Peter Soprunov • Feb 3, 2020 at 8:22 AM

Liz, this article is amazing! It’s profound, erudite, and emotionally charged.

<3