An Open Letter to Student Council

It’s time to stop segregating graduates by gender

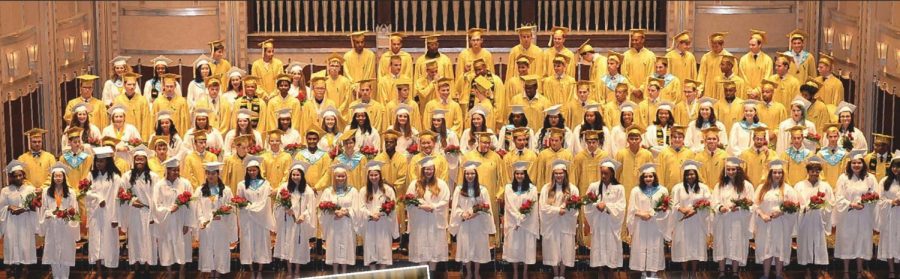

Class of 2019 commencement at Severance Hall color codes the gender binary.

Dear Student Body President Lena Leland,

Executive Vice President Joelle Rosenthal,

Student Body Vice President Elizabeth Metz,

Student Body Secretary Greg Perryman,

Student Body Treasurer Emily Fan,

Class of 2021 President Sanjana Murthy,

Class of 2021 Vice President Sabrina Fadel,

Class of 2021 Secretary Chelsea Zheng,

Class of 2021 Treasurer Rachel Rosenthal,

Representatives of Class of 2021,

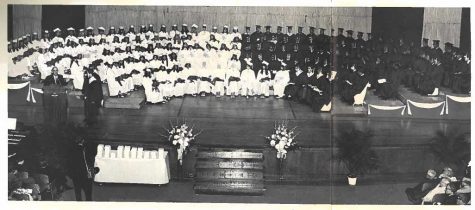

Above is a photo of the class of 2019’s commencement ceremony at Severance Hall on June 4, 2019. Approximately two years from that date, the class of 2021 will have our own commencement ceremony, presumably at the same venue. We the class of 2021 have a decision to make: are we to leave this school as two separate groups, draped in two different fashions of academic regalia, or graduate as a unified class?

I do not know when the decision was made to have boys wear gold and girls wear white at commencement. A photograph I managed to find in a 1968 Oculus has a clear segregation of color across gender, but it is hard to tell if the white-and-gold pattern had already been established (perhaps the graduates in the photo are wearing white and black).

Having interviewed BHS grads from the 70’s and 80’s, I’ve come to the conclusion that the tradition started in the 60’s and was followed every year until the present. It is reasonable to assume that this tradition is greater than 50 years old.

American culture has made radical, structural steps towards gender equality since 1968. We have gone from the Stonewall Uprising to the Obergefell decision. We passed the 1994 Violence Against Women Act and allowed women to serve in military combat positions.

At the time of my writing this, the Supreme Court is deliberating on whether or not transgender, non-binary, and queer people belong in our workforce. In this “baby steps” process, it is necessary we abolish this tradition as well.

Dr. Lyz Bly (known as “Dr. B.” by her students), from the Women’s and Gender Studies Program and Communications Department at Cleveland State University, wrote the following in an email when asked about Beachwood’s gendered robe tradition:

Outmoded traditions such as the ‘gendered’ (white/blue) graduation robes serve to separate women and men, placing them in oversimplified black and white categories. In Women’s and Gender Studies, we refer to this as the ‘gender binary.’ In this historically gendered notion is the idea that gender and sex are polarized opposites with woman/female at one end of the spectrum, and man/male at the other. Not only is the kind of polarization limiting for cisgender individuals, it is problematic for those who don’t ‘neatly’ fit into ‘masculine’ and ‘feminine’ gender identities.

I could end my assessment of this tradition at “cisnormative ergo problematic”, but that would be not only lazy on my part, but would create a rather unconvincing argument. The problem is not just that boys and girls are being explicitly segregated, the problem is that the narrative created by this tradition affirms preexisting patriarchal values.

When I asked Student Activities Director Craig Alexander, who is in charge of the commencement ceremony, about abolishing the tradition, he told me that it was very doable but that he did not see the point to it. He assured me that any transgender or otherwise motivated student wishing to wear the robes of the opposite sex would be offered that choice, but argued that forcing a homogeneous color scheme would be unfair.

“Why take away the choice of people to wear white and gold, like, say, [their predecessors] did? I don’t think it’s fair to take that choice away,” he said.

Choice is a contentious idea in the feminist sphere—if a choice is being made in a patriarchal context, is it the individual, or the patriarchy truly making the choice? How could we ever tell if a woman was acting on her own volition, or acting in conjunction with the patriarchy?

Take, for instance, the decision to become a stay-at-home mother. While it is unfair to criticize an individual woman for having such a lifestyle, the fact that women are, on average, far more likely to become stay-at-home parents is certainly not value-neutral. At the extremes of this phenomenon, we encounter discussions of choice and female genital mutilation or arranged marriage. There are times when, paradoxically, relinquishing choice is more empowering than allowing it.

My assertion is not that it is unfair for girls to receive a bouquet of roses while boys don’t get one. My assertion is that giving roses to girls alone creates a misogynistic atmosphere and is ultimately detrimental to graduating girls. In 1976, a young Ruth Bader Ginsburg famously addressed an amicus brief on behalf of the ACLU to an all-male Supreme Court deliberating on Craig v. Boren. The case involved an Oklahoma law which allowed women aged 18 and up to purchase 3.2% beer, but barred men from doing so until they reached 21.

Ginsburg asserted that this law lent legal credence to the notion that young men were intrinsically more reckless than young women and young women more responsible than young men, affirming the toxic “boys will be boys” canard while presenting women as delicate, morally pure creatures. The court ruled against the law, concluding that statutory and adimistrative discrimination on the basis of sex warranted intermediate scrutiny under the 14th amendment.

This is the argument I now make—the message communicated and attitudes cultivated by giving girls roses at commencement and dressing them in white impede women’s achievements.

In my opinion, choice of colors is an example of either intentional or unintentional gender coding, communicating a specific message. The clearest message I could initially interpret was one of value to the social order, with more economically valuable men robed in gold, and meek, submissive women robed in white.

Dr. Barbara G. Hoffman, Director of Cleveland State’s Visual Anthropology Center in the Department of Criminology, Anthropology and Sociology, and a longstanding member of the WGS faculty, had quite a bit to add to my original assessment:

Clothing the women in white and offering them flowers could also be an analogy to wedding attire, perhaps a throwback to the very old adage that men go to school to get a diploma; women to get their MRS. It’s hard to believe a respected high school like Beachwood would want to send that message.

White also symbolizes the moon, an allusion to women’s monthly menstrual cycles. It can represent sexual purity too – the origin of the white bridal gown. Gold, in contrast, might represent the sun. Without the sun, life cannot exist. The moon rules the tides, but is not a sine qua non for life on earth. Again, not the kind of message an educational institution in the 21st century wants to transmit.

If the purpose of graduation is to celebrate the attainment of a level of education, why not clothe all the graduates the same way? Doing so would obviate any perception of gender discrimination, whether deliberate or unintended. Maintaining gendered differences can easily be read as supporting gender discrimination.

While some may dismiss such an analysis as grasping at straws, I would argue that there is almost nothing value-neutral or insignificant in our daily experiences. Every decision has a meaning because that decision has a wider historical context and has the potential to cultivate a certain perspective.

Take for example that, according to the American Association of University Women, the ratio of women’s median earnings to men’s median earnings was 82% in 2018 for the US. In such a climate of professional sex-based inequity, we should be doing all we can to empower women, and engender (pun intended) the attitude that they are equal to men.

When you give a young woman a bouquet of roses at her graduation, which is an important step on the path to her professional life, you invoke centuries-old images of damsels in distress being brought roses by generous, more powerful men.

This is not a gender discrepancy meant to solve the pay gap, like, say, Girls Who Code. This is a reinforcement of attitudes that gave us a pay gap in the first place.

No one doubts that there are sexist traditions in our society. At this point, that’s kind of a base assumption. But not all sexist traditions are created equally. The tradition of women taking their husband’s name is pervasive and the vast majority of American women abide by it.

Wearing white at commencement, on the other hand, is rather 50/50. From what I’ve observed looking at graduation photos from high schools across the US, about half the time girls wear white while boys wear a darker color, and the rest of the time, everyone wears the same color. You are in a position to abolish this tradition without transgressing some ubiquitous, nefarious institution. All you have to overcome are 50 or more years of Beachwood history.

When I graduate in a couple of years, I don’t want to be dressed in a different color than my female friends. I want it to be clear that we are all equals, having shared a collective high school experience, now on divergent paths across the professional and academic world.

And, as Dr. B. wrote me, “Right now the only thing we truly control is how we (all of us, and women, less so) use our own bodies, minds, and words in the world. Clothes and uniforms and robes matter because they are symbols for how we want (or do not want, in the case of your robes) to be understood in the world.”

I also find red roses dreadfully trite. But that’s neither here nor there.

Thank you for your time,

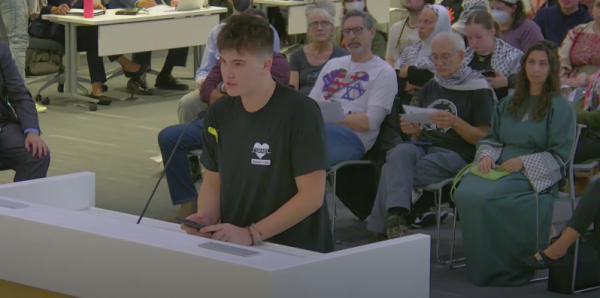

Peter Soprunov

Class of 2021

Alice Soprunova (she/her) began writing for the Beachcomber in 2019. She covers stories pertaining to issues of social justice inside and outside BHS....

Peter Soprunov • Nov 11, 2019 at 3:20 PM

I have been informed by Beachwood High School that the school will be switching to a one-colored robe scheme at this years’ commencement ceremony. Take that, gender!