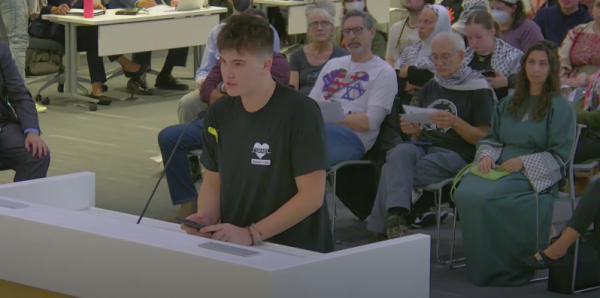

It’s Time for a More Diverse English Curriculum

There is an unsettling pattern in the BHS English curriculum.

When reflecting upon the books we’ve read and the lessons we’ve learned at Beachwood, this pattern becomes very apparent. Our English classes are so… white. And male. And it’s a problem.

While we may read books about race relations and historical injustices with a couple of female writers here and there, an overwhelming majority of the books we read are written by white men.

This is not hard to see. It is also not hard to believe, given that our dominant culture has always held white men in higher esteem than other populations, whether we are aware of it or not.

The largest number of mandatory full-length books written by a woman in any single BHS class is three of eight books assigned. The largest number of full-length books written by a person of color is two of seven. There are classes at BHS that do not feature female authors at all.

The teachers at BHS are not at fault here. No, this issue is much bigger than us. But correcting the problem on a district level is not a far-fetched goal.

Our teachers are aware of this issue, and they are working together to integrate more diversity into the curriculum.

It is English teacher Carrie Shapiro’s first year teaching at Beachwood, and she has already noticed this problem. After walking into a class with a set curriculum featuring very little diverse representation, Shapiro is working with other teachers in the English department to bring more diverse literature into our school.

“I’m hoping, as a new teacher, that we can make a change in providing new voices for our students,” Shapiro said.

The traditional texts read in most American high schools contribute largely to the issue. White male authors like Fitzgerald, Salinger and Shakespeare are considered staples in every learning environment. They are revered to the point where it’s treasonous to question them.

However, this frigid standard for classrooms is toxic as it restricts growth. As the world around us evolves, our cookie-cutter classes must evolve with it, or we will learn nothing more than how to read and write. Literature, when immersive and diverse, allows us to expand our minds and our worldview. Our classes should do the same.

That isn’t to say that the tried-and-true classic texts are not valuable. According to sophomore English teacher Todd Butler, many of the classics touch upon human values that are extremely important to us.

“I can’t imagine not teaching Shakespeare,” Butler said. “[His work] transcends gender and race and is a brilliant scope into the human experience.”

While this may be true, as the curriculum fills to the brim with classics, there is less and less room for modern, diverse texts. As Butler later pointed out, the teachers must allow flexibility as modern ideals progress.

Of course, we should not be integrating diverse authors into the curriculum merely for the sake of doing so. Exchanging an exceptional book by a male author with a subpar one by a female author is not productive.

But refusing to make the effort to find an equally effective and appropriate book written by a non-male or non-white writer is refusing to recognize the fact that such literature exists. There is an abundance of extraordinary works by diverse authors that meet the thematic standards of Beachwood classes. They are not hard to find if we bother to look.

With this push for diversity, English teachers are challenged to step out of their comfort zones and abandon books that they may have been teaching for years.

“We must always be aware [of race and gender] and make the effort not to settle for what we’re used to,” Butler said.

Casey Matthews, who teaches freshman and senior English as well as her African American literature elective, is also working to diversify her classes with more non-male and non-white writers and protagonists.

“There are a lot of people who are uncomfortable changing their set curriculum,” Matthews said. “But good teachers must also be good students and change to meet the needs of the times.”

When designing a curriculum, there are many things a teacher should consider. Evan Luzar explained that a driving factor when considering texts for American Literature was the possibility that some students might not take another literature class after high school graduation. An important component in the conversation was considering what texts are an important part of our cultural and literary history.

“If a kid goes off into this world and doesn’t know what The Great Gatsby is and hasn’t read it, they’re missing a lot of touch points in terms of cultural conversation,” Luzar said.

Luzar brings up a good question to consider. What is the purpose of teaching literature? If we’re taking the classes just to learn how to analyze literature and write persuasive essays, our English department is doing a phenomenal job. If we’re trying to broaden our mindsets to see the world in a diverse context, however, we’ve got a long way to go.