“Marriage Story” Arguably Johansson and Driver’s Best Work

The official movie poster for “Marriage Story,” which came to Netflix US on Dec. 6.

In mid-December, after a two-month hiatus from Netflix, I finally caved in and sat down to watch the first thing the web site’s algorithm fed me: Noah Baumbach’s latest production, Marriage Story.

Completely unaware of the film’s six recent nominations for the 2020 Golden Globe Awards, I stumbled blindly into Baumbach’s heartwrenching divorce opus and into the lives of separating couple Nicole (Scarlett Johansson) and Charlie Barber (Adam Driver).

Of course I knew both Johansson and Driver through their respective portrayals of Black Widow and Kylo Ren, but I wasn’t familiar with the rest of their filmographies. Johansson and Driver’s performances in Marriage Story became my first impression of both leading actors outside of the action/science-fiction genre, and they certainly did not disappoint.

Marriage Story begins with Nicole and Charlie each describing what they like about the other. The audience is privy to intimate snapshots of the couple’s life with each other and with their eight-year-old son, Henry. From first glance, the Barbers seem to be a loving and happy family.

From the raw sincerity of both partners’ lists, it is clear that the couple was once in love, so when Nicole vehemently refuses to read her list aloud to Charlie and their divorce mediator, the audience is left to wonder what went wrong.

Over the course of her marriage to Charlie, former film actress Nicole was forced to refuse many offers from directors and producers in Hollywood in order to stay with her husband and son in New York, wholly devoted to her role as a mother and as the star in her husband’s plays.

However, her dreams lay in Los Angeles, and though initially proud to be the center of Charlie’s productions and of his attention, her happiness dwindles as Charlie repeatedly rejects her opinions in favor of his career (“I got smaller,” Nicole recalls to her divorce lawyer. “It would be so weird if he had turned to me and said, ‘And what do you want to do today?’”).

What struck me hardest was how convincingly both leading actors played their parts. One of the scenes I loved most was Nicole’s monologue, when she recounts to her lawyer the reasons she was attracted to Charlie–his genius, his sociability and his creativity–which turned into the reasons she left: she felt as if he left her no room to flourish.

Johansson recites the speech, which runs on for several minutes, all in one-go. She talks through her tears, voice breaking as she desperately defends her actions in long, rambling sentences, sometimes having to stop and backtrack through her narrative to anchor herself back in the present. The authenticity of Johansson’s performance made Nicole’s story come alive. This is the first time the audience fully understands Nicole’s pain in leaving Charlie, and also her overwhelming need to do so.

To make matters worse, in Charlie’s incapacity to handle the growing distance in their marriage, he seeks solace in a one-night stand, which, though racking him with enough guilt to never go through with another, is ultimately (and understandably) the last straw for Nicole.

Driver too, delivers a powerful performance as Charlie struggles with the possibility of losing custody of his son. It is obvious Driver pours all of himself into his role; his calm resolve extinguishes at the mention of losing his son, his lip quivers unsteadily when anger and frustration overpower his character. As someone in a YouTube comment puts it, “I’ve never seen an actor who doesn’t even act. It’s more like I’m watching someone’s life.”

Charlie’s selfishness in wanting to stay in New York stems from his need for a stable home: a result of briefly mentioned abusive and/or neglectful parents. His desire for family is his fatal flaw, his Achilles’ heel, as he tries to hold on to both the family he’s found in his theater company and the family he’s made with Nicole and Henry.

In one scene, Charlie is both tied up in a phone call with Nicole’s divorce lawyer and trying to direct his production at the same time, in the end unable to successfully handle either. This is a lovely parallel to Charlie’s larger character arc, wherein his desire to retain both of his former families causes him to lose parts of both.

By the end of the film, Nicole’s and Charlie’s worlds are flipped. In the beginning, Nicole grapples with guilt and pain in divorcing Charlie as Charlie’s on top of the world, with a newly received MacArthur grant and a show moving to Broadway. In the end, Nicole is the one on top of the world, with a Grammy nomination for directing and a hot new boyfriend, as Charlie struggles with the connection he’s lost with Nicole, her family and their son.

We see this dramatic change when Nicole sings “You Could Drive a Person Crazy,” from Stephen Sondheim’s Company, with her sister and mother during a party. After the scene ends, the film pans to Charlie sitting on the edge of a table, talking with members of his theater company about his divorce. It is the same table we see at the beginning of the movie, right before Nicole leaves for Los Angeles and Charlie prepares to move his play to Broadway. He suddenly stands up as he hears a tune he recognizes, and begins to sing.

The song is “Being Alive,” also from Sondheim’s Company, but it carries a completely different tone than Nicole’s song does. While “You Could Drive a Person Crazy” sounds cheery and carefree, Charlie’s performance is built on raw, unhinged emotion. His production team can only sit and watch as their director takes himself apart on stage.

Not only does this scene perfectly juxtapose Nicole’s performance, it also perfectly parallels Nicole’s emotional monologue at the beginning of the movie about wanting to “come alive.” Just as Nicole felt a part of herself die during their marriage, Charlie feels a part of himself die after their divorce. Charlie was a temporary replacement Nicole ultimately did not need; Nicole was an essential constant Charlie ultimately could not replace.

However beautifully acted by Johansson and Driver, each character’s development is lacking in important ways. After about the 45-minute mark, the film abandons Nicole’s point of view. The next 90-or-so minutes focus almost entirely on Charlie’s perspective (possibly because Marriage Story is modeled after the director’s own divorce), so when Nicole starts to take significant legal action against Charlie with her divorce lawyer, her behavior seems unreasonable and her character, along with her lawyer’s, becomes nearly villainous.

While a third of the film centers around Charlie’s viewpoint, we never get to see his character truly develop past his love for theater and his love for Henry, which seem to be his only redeeming personality traits (as opposed to being a selfish and unfaithful husband). These traits are enough to garner sympathy, but perhaps if we got to see more of his backstory, we would be more in tune with his personal tragedy in losing a relationship he cared about.

Despite shortcomings in character development, Marriage Story still manages to evoke powerful emotional responses by utilizing various conflicting tones.

In one scene, Henry excitedly asks his dad to “do the thing with the knife” in front of custody evaluator Nancy. Charlie hilariously attempts to dismiss this comment, hoping that the evaluator doesn’t see the request as proof of bad parenting. Yet later, when Charlie and Nancy are sitting alone in his living room, Charlie brings out the knife Henry mentioned to break an uncomfortable silence.

“I pretend to cut myself, but I retract the blade,” Charlie explains, as he pantomimes the motion with the knife. He chuckles a little to himself before seeing the look of terror on the evaluator’s face, and follows her gaze to the gigantic gash he accidentally made on his arm. The scene then becomes a constant back-and-forth between him and the evaluator, the evaluator repeatedly asking if he’s okay and Charlie repeatedly responding yes, even as blood starts to seep through his shirt.

When Nancy leaves, Charlie rushes into the kitchen and runs his arm under the faucet, then wraps his wound up with paper towels. He collapses onto the floor, seconds before his son walks in to get a glass of milk. As Henry passes him, Charlie rolls onto his side, hiding his arm.

The knife scene is a fantastic example of how Marriage Story uses juxtaposition of tone to elicit reactions from its audience. It starts off light and humorous, with Charlie fumbling over his words as Henry’s absent-minded comments threaten custody conditions. Within a few minutes, however, the situation turns dark and dramatic; suddenly Charlie is bleeding profusely and the evaluator is desperate to get out of the room.

Suffice it to say that, while flawed, Marriage Story successfully combines a variety of different elements to create a comedy-drama masterpiece, and while opinions may differ, Johansson has never been so convincing and Driver so captivating as in this film. If discussion on individual character arcs and song theory doesn’t move you, then at least watch it for the actors. You won’t regret it.

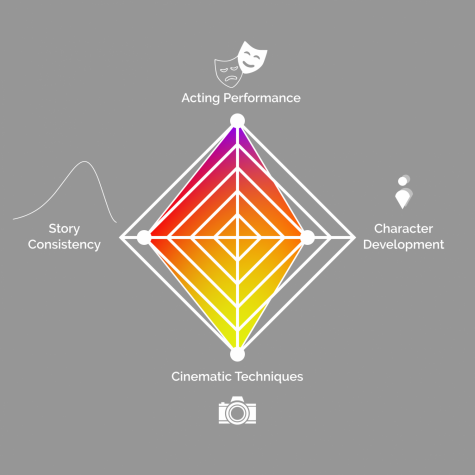

Based on acting performance, story consistency, character development and cinematic techniques, here’s where “Marriage Story” stands.

Amy Chen began working for the Beachcomber in the spring of 2018. In addition to managing site design, she illustrates and covers a variety of topics in...

Yang began illustrating for the Beachcomber in the fall of 2019. In addition to this, he participates in the school's Academic Challenge and Science Olympiad...