Is it still possible to have a political conversation that doesn’t devolve into anger and cynicism?

Beachwood, a historically diverse and progressive community, has been confronted with this question recently. Political clashes in the school and on social media in the last year have created tension among students, just as in the broader society.

In an effort to address this, school administrators brought in a program intended to bring students together.

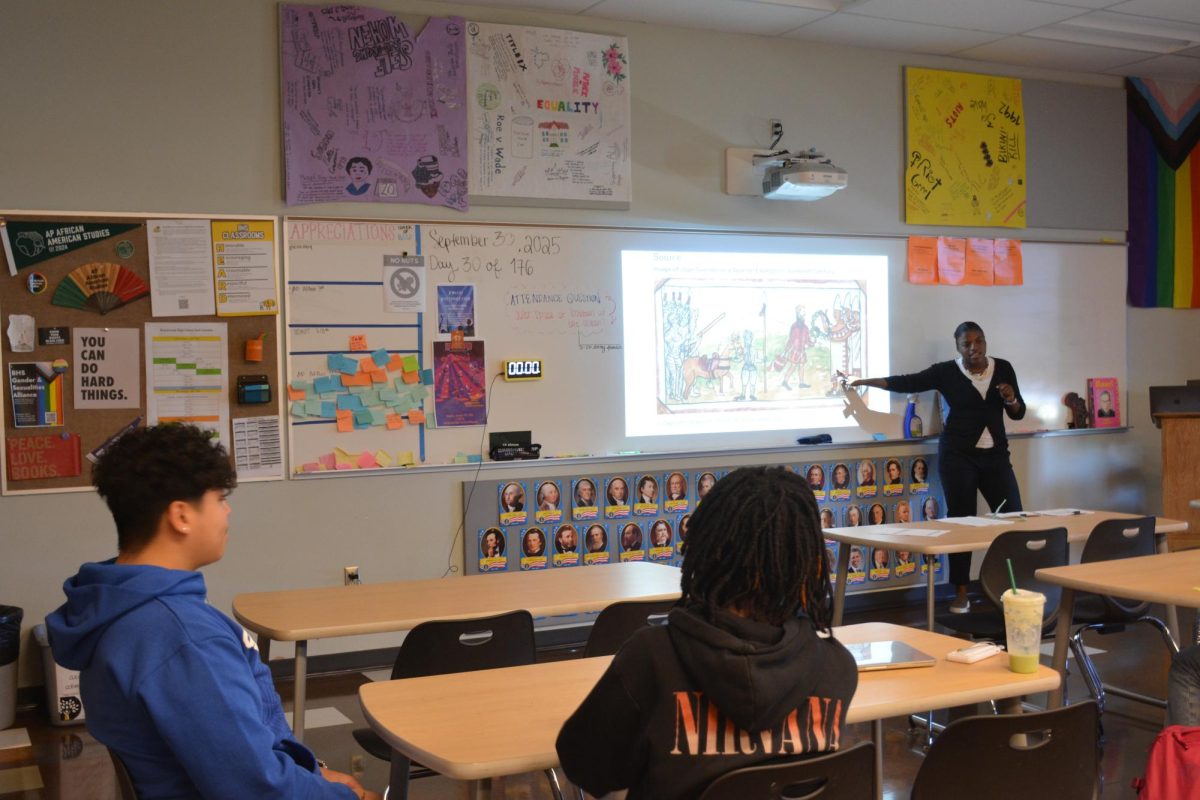

The School-Student Problem Identification and Resolution of Issues Together (SPIRIT) program, developed by the U.S Department of Justice, has held two events at BHS this year.

“[The program is] focused on having safe conversations with students that you may not have conversations with in general,” Asst. Principal Aubrei Erkins said. “If we could find ways that students can have safe conversations with each other without it turning into an argument, that’s a life skill.”

At each SPIRIT program, students sit down in discussion groups of peers and brainstorm a list of topics. Then, student facilitators help them refine those ideas and work toward possible solutions.

The first event, held on Sept. 12, included a group of approximately 60 students, and the second, on Jan. 9, included the entire student body meeting with their grade level classes.

The Justice Department designed the program to teach students how to facilitate conversations in an age of political polarization.

“Nowadays, sharing your political beliefs feels like a taboo topic,” senior and program facilitator Osita Ogor told the Beachcomber in September. “In school, my opinion on situations is my opinion and my opinion only.”

Students and teachers alike have expressed discomfort about engaging in political discussions in school. A study in 2022 found that 70% of principals nationally have reported substantial political conflict over hot button topics like LGBTQ+, race and others that can spark controversy, and the climate has only gotten worse.

This rise in conflict is likely the result of a general trend among Gen. Z students having increased political polarization. Some point the finger at social media as the driving factor.

“I’ve taught for 19 years, and especially since Instagram and TikTok have become wildly popular, I have seen more students engaged in current events than I did back then,” said social studies teacher Pam Crossman. “Because we have information at our fingertips every single second of the day, I think that accessibility has resulted in more kids becoming engaged.”

Social media has played a huge role in shaping, radicalizing and polarizing the political landscape.

“Most kids get their first exposure to the news via social media. For some, they then take what they’ve seen on social media and they fact check, finding more credible resources and that kind of thing,” Crossman said.

However, videos on social media often end up being very surface-level, and most teens don’t take the time to look further.

“I fear that sometimes students only get that taste of what they’re seeing via an algorithm on TikTok or Instagram, and then that’s where the curiosity ends, which cannot be a good thing,” she said.

The ability to see past the echo-chambers of social media algorithms is something that not many people, especially teenagers, are able to do. Media literacy and awareness are now going to be fundamental skills that many schools, Beachwood included, are beginning to incorporate into their curriculum.

“We have to do a better job of arming students with fact-checking skills,” Crossman said. “How do we trust and verify, and what are other perspectives?”

Besides media-literacy, there’s another problem plaguing schools–arguably the whole country–and it’s a lack of civil discourse.

A study by the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression found that almost a quarter of students censor what they say at least a few times a week in political conversation with friends.

Junior Ilana Thal often finds herself in the middle of the road when it comes to politics.

“I would consider myself highly uncomfortable sharing my political beliefs,” Thal said. “I have friends that are very liberal and I have friends that are very conservative, and my viewpoints tend to be [moderate]. I think of things that offend my liberal friends and then I think of things that offend my conservative friends, but I keep that to myself. I don’t want to base my friendship on politics.”

“Unless someone genuinely wants to hear it in a non-confrontational way, then I usually try to stay away from [political arguments] because usually people react in a very aggressive way. It’s just not like how I want to see my friends,” she added.

This aggressive response is familiar to many people. To some, it feels like the country has never been more divided when it comes to beliefs, and that passion, when left unchecked and unhoned, almost always causes frustration.

“People see politics as black and white, but I usually see things in the gray,” said Thal. “The problem is once they see you having different opinions, they try to shove their own opinions in your head.”

This has been a common viewpoint among students. A lot of people think that this behavior and aggression is caused by a number of factors, including family values, culture and education.

“It’s just bad for everyone, I feel,” junior Noah Beilstein said. “Everyone would just argue all the time…nobody is able to conduct themselves in a way they can have a good debate. They’re just too radicalized, they don’t know enough about the topic to speak about it properly, so they just take stuff from TikTok or the internet and say it’s real.”

“I feel like people are taught that if it’s not your opinion, it’s wrong. I think it’s just the environment here with families and teachers. I think it’s the culture that we have here,” said senior Isaac Gorodeski.

“It’s hard. It’s not fun to feel like you’re the only one who feels a certain way in a group of people. I think it has less to do with the kids in the classroom, and more to do with the structures of the school,” Crossman said. “We have to make sure that we are valuing people’s opinions despite the fact that we might not agree with them.”

Despite these concerns, multiple facilitators for the last S.P.I.R.I.T. assembly said politics were rarely mentioned.

“My groups mainly talked about lack of school spirit, issues with teachers, athletics budget management…Literally nobody mentioned politics,” junior and program facilitator AJ Myers said.

Myers spoke with other facilitators and reported that they had similar experiences. However, this outcome isn’t surprising, considering students have described themselves being uncomfortable sharing their opinions with their peers.

“We need to do a better job of teaching [students] how to communicate effectively and respond to viewpoints that we disagree with,” Crossman said.

The dilemma is whether the school should encourage students to have these difficult conversations or not. Students seem to be split on whether it’s the school’s responsibility or the students’.

“If [students] want to have real civil conversations about it, then yeah, I think the school should encourage it,” Beilstein said. “I mean, it’s good for people to talk about this stuff because we are ‘the future’, you know?”

On the other hand, some students say that politics still shouldn’t have a place in school.

“I don’t know if political debate should be encouraged. I don’t think that should be the purpose of school,” Gorodeski said.

“Even though politics are important, teachers don’t want any students either fighting or getting in disagreements that might disrupt the learning environment,” Thal said. “…Why would I talk about politics in my science class, especially an AP curriculum? I think they’re just trying to focus on the subject and not politics.”

However, these conversations are bound to happen, regardless of whether teachers intend it. Erkins feels that students have the capacity if they learn the skills of civil conversation, and that the SPIRIT program will help them gain these skills.

“Students have the ability to [discuss civilly], for sure,” she said. “I think with this program and as we continue to train these facilitators, it’ll give more students those skills.”

“There are almost 20 students who can now, if it came to like a debate or something going on in the classroom, they would be able to refocus it or organize it.” she added.

As political radicalization grows at BHS, fostering civil discourse and media literacy could be key to bridging divides among students and keeping this community united.