This summer BMS English teachers Kate Vitek and Carrie Shapiro traveled to Poland to gain firsthand experience touring Holocaust sites, which will help enrich their curriculum.

The two journeyed to three main cities: Warsaw, Lublin and Kraków. The trip simulated a graduate-level course for high school students and teachers as well as donors, guided by two Holocaust scholars.

Vitek explained that her direct experience will make her more effective when she teaches about the historical atrocities.

“When I’m talking about the Holocaust with students, if they’re asking me about something like Auschwitz, in my mind’s eye, I’m seeing Auschwitz,” Vitek added. “It brings authenticity to the classroom when I’m not just saying things I’ve read or facts I’ve memorized, but I can speak to it from some personal experience.”

Vitek and Shapiro, funded by the Jewish Education Center of Cleveland, were the first Cleveland-area teachers to collaborate with the Pittsburgh-based Classrooms Without Borders on their study-abroad trip.

They were accompanied by Holocaust survivor Howard Chandler, who guided them through the places where he had endured unimaginable hardships. Howard Chandler has led the Classrooms Without Borders study abroad trip for over a decade.

“He took us to his house,” Vitek said. “He walked us across the street and said ‘Here’s the Market Square. This was the last time I saw my mother and sister…’ Then, he took us to a steel factory where he worked for a year or two as a slave laborer.”

Vitek and Shapiro felt that they better understood the individual suffering, grief and resilience that Holocaust victims endured.

“He showed us the pipes and the ceilings and the way he used to have to crawl through them,” she added.

In Warsaw, the group learned about the ghetto uprising and explored museums to learn about Jewish history and the persecution that preceded the Holocaust.

They also visited the Emanuel Rosenblum archives at the Jewish Historical Institute.

In Lublin, the Holocaust hadn’t left any Jewish survivors to share their stories. During their visit to the Grodzka NN Theater, program participants witnessed the organization’s diligent efforts to collect and compile records to preserve the memory of the victims.

“Kraków was the one city that was completely untouched during the war because it’s all original medieval architecture,” Vitek stated. “It’s a beautiful city.”

Vitek reflects on the lessons she will bring back for her students.

“As a teacher, you’re not just focusing on the Holocaust; you’re teaching kids to contextualize it — the whole history that led up to it and asking how that impacts Poland today,” she said. “What does that look like when you have millions of people absent who should have been living there? There’s always the phrase, ‘never forget.’ But we need to ask, how do you remember?”

Her ultimate goal is that her students will also go beyond the facts.

“I want my students to be critical thinkers who don’t just accept what they’re told, but question it, think about it, research, and go beyond that,” she said.

The experience left a lasting impression on Shapiro, and made her more aware of the profound void left by the obliteration of an entire community.

“One significant takeaway was that you could feel the presence of the absence, which is a very visceral feeling,” she said.

Shapiro also wants her students to think about the role of bystanders in allowing humanitarian catastrophes to take place.

“There’s some interesting footage I want to show my students of Polish people who lived right outside the concentration camps, and it captures their reaction to walking through the death camps,” she said.

The two teachers also brought stones from the Beachwood community to Treblinka, each bearing the engraved names of Holocaust survivors to honor families, students, and friends. The Treblinka memorial site, a haunting former concentration camp situated an hour outside of Warsaw, is a touching testament to the identities of 17,000 Jewish victims, each stone etched with the name of the place they once called home.

“I got two stones from personal friends whose grandparents were survivors,” Shapiro said. “It was a touching moment to be able to represent the family by traveling with the stones.”

Vitek emphasized that literature can be a crossroads between people and politics and can serve as a tool for change, albeit in small ways.

“I think as you get older, you have an increased appreciation for nonfiction and the recognition of history as a lived experience as opposed to just facts that you are memorizing for a test,” she said. “So, for young people, like eighth graders…I feel literature helps them to appreciate the reality of what they’re learning beyond just facts.”

She explains the revolutionary influence of Elie Wiesel’s courage to share his experiences in the memoir Night. Shapiro incorporates Night into her curriculum to help her students better understand the lived experience of oppression.

“[The book can] get an emotional response even from young readers, opening them up to empathy and asking ‘what can I do in 2023?’” she said.

Shapiro and Vitek hope the new curriculum they develop will complement the upcoming 8th-grade experience at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. later this year.

In the months since they returned, Vitek and Shapiro are actively disseminating their knowledge throughout the community by delivering presentations at the Jewish Education Center of Cleveland, engaging in discussions with their peers, and instilling these lessons in their students.

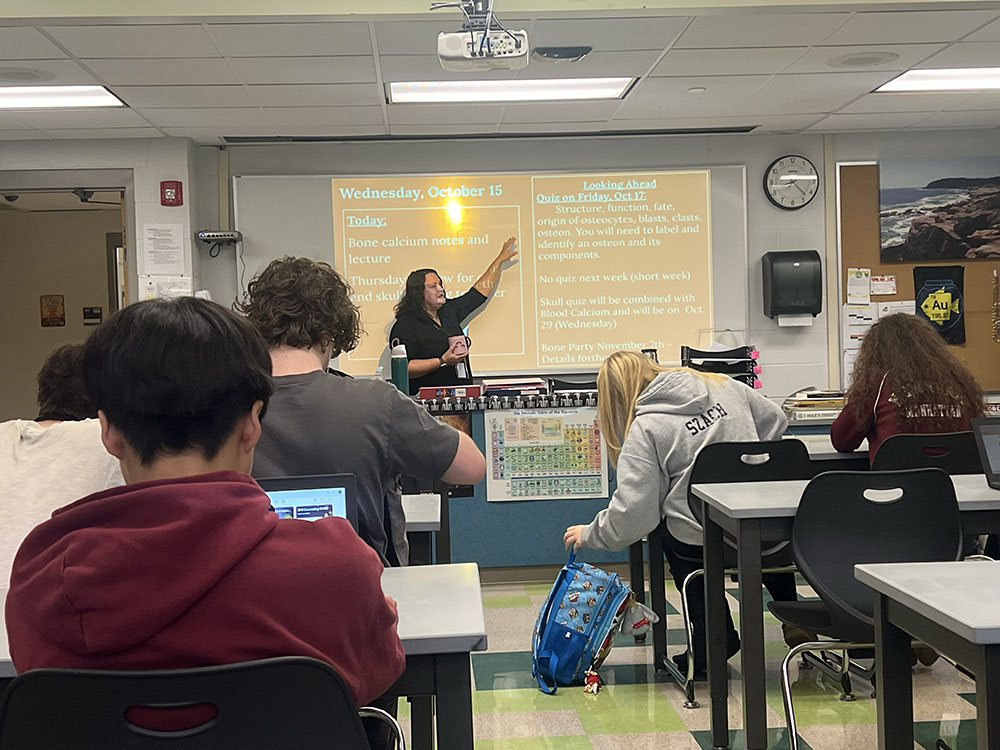

At the high school level, the Holocaust is taught in World Studies, focusing on the American government’s response. Additionally, in human rights, the Holocaust is taught through a five-week unit based on curriculum developed by an organization called Facing History and Ourselves.

Human rights teacher Pam Crossman explains the Facing History approach.

“[The class focuses on] identity first, then group membership and how over time, in different situations, there are examples of people being marginalized and how propaganda has attacked groups of people all throughout history,” she said.

One of the course objectives is for students to recognize historical continuities and draw connections between events like the Holocaust and more recent events like South African Apartheid, the Rwandan genocide and current events in the United States.

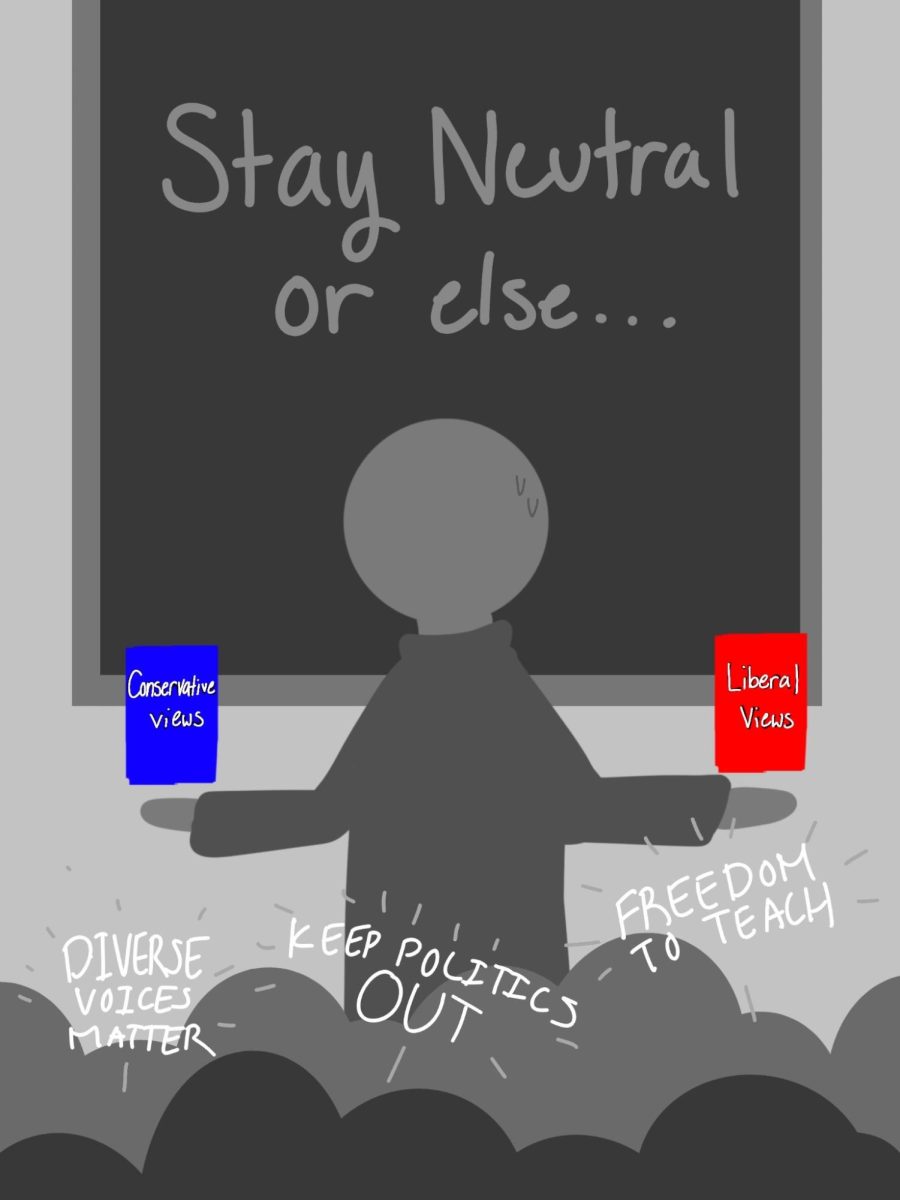

Teaching historical injustices also addresses the challenge of confronting denial. As Crossman suggests, responding to these perspectives is crucial for progress but is fraught with challenges.

“There are going to be people I fundamentally disagree with about a whole host of things,” she said. “I can say we disagree, and you won’t be in my universe. But, it actually causes the divide to get greater.”

“So I think it is absolutely necessary to reach out and try to understand where people are coming from as opposed to completely dismissing them,” she added.

Crossman urges students, teachers and families to utilize local resources and discuss the imperative role of experiential learning. She used to invite Holocaust survivor Stanley Bernath to talk with her Human Rights class. Bernath died in 2019, and his interactive hologram can now be viewed at the Maltz Museum.

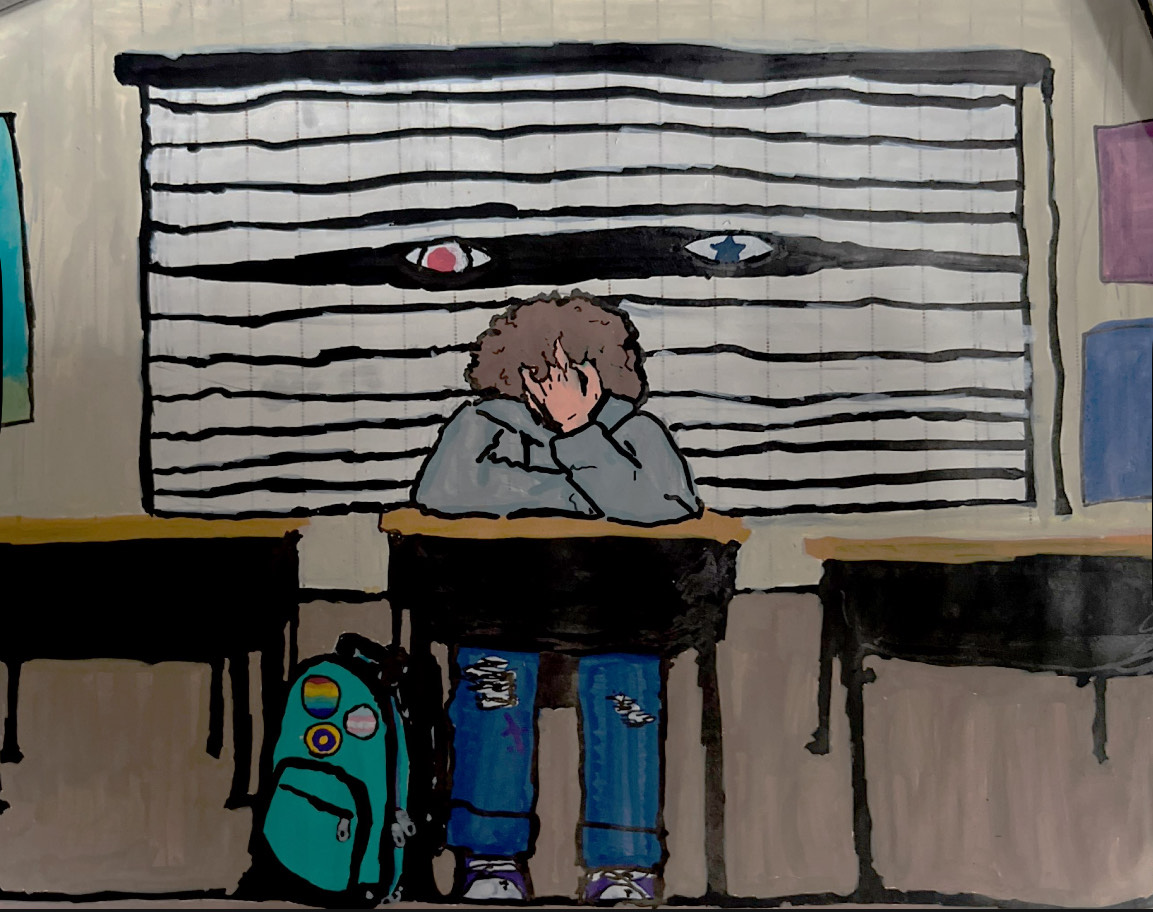

“What I love about this course is that the goal is to try and help people become more human and more empathic,” she said. “Empathy is kind of like a muscle, and if you don’t exercise it, it atrophies.”

“The goal is to hopefully provide kids with the tools to stop bigotry, racism, bullying, hatred or homophobia in real time,” she added.

![“My parents have always said that education is important. My parents are Chinese immigrants, I'm Chinese American, [and that's a] value that has always been ingrained in our community,” said Senior Lyndia Zheng, pictured with Tony Zheng](https://bcomber.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/DSC_4244.jpg)