Celebrating Black History Through Song

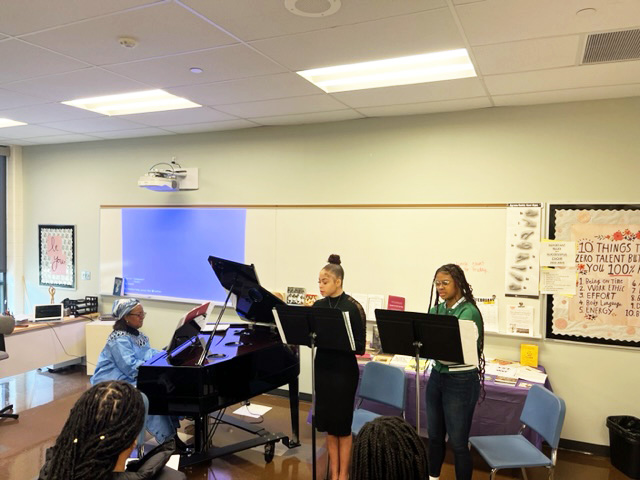

Junior Miyani Mercer and sophomore Junae Simmons joined Dr. Harrell in singing “This Little Light of Mine” and “Steal Away to Jesus.”

A group of BHS students attended a musical presentation on Negro spirituals in celebration of Black History Month on Tuesday, Feb. 21.

The presentation was hosted by Dr. Babette Reid Harrell, who has been studying Negro spirituals – songs written by enslaved African Americans – formally since 2013. She earned her PhD in music from Boston University in 2019.

It was an engaging musical performance of five different pieces.

“These songs were a way to cope, they were coping mechanisms,” Dr. Harrell said.

Dr. Harrell’s interest in spirituals stems from both her roots and her upbringing.

“[They] connect with my heritage as an African American woman,” she said. “I grew up in the church where singing is a part of the service, and [spirituals] connect with my spirit like no other music.”

This connection is what led her, in 2013, to begin studying spirituals through research on the Wings Over Jordan Celebration Chorus, a choir continuing the legacy of Cleveland’s Wings Over Jordan choir, which performed gospel music and spirituals from 1935-1978.

Dr. Harrell earned her PhD with her dissertation: Preserving the Negro Spiritual: A Case Study on the Wings Over Jordan Celebration Chorus.

In preparation for the event, juniors in Josh Davis’s AP English Language class read Of the Sorrow Songs, a chapter from W.E.B Du Bois’ book The Souls of Black Folk. This selection described the origin and evolution of Negro spirituals.

Writing in 1903, Du Bois described spirituals as a sacred art form.

“[Negro folk-songs] are the singular spiritual heritage of the nation and the greatest gift of the Negro people,” he wrote.

Dr. Harrell performed several of the songs referenced by Du Bois.

To open her performance she played On Bended Knees by Harry T. Burleigh on piano, a song based on the spiritual Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen, and was followed by a video of “the first black superstar” Paul Robeson performing Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen with its original lyrics and tune.

Next, Dr. Harrell introduced a small group of students whom she included in her performance as a way to authentically present the material.

“I knew I did not want to do this performance by myself,” she said, “[These spirituals] are really meant to be sung. I’m not really a singer, so I thought why not involve some students?”

So she approached junior Miyani Mercer and sophomore Junae Simmons to join her performance as a small ensemble accompaniment. BHS orchestra cellist Jonah Wolfe was included in the performance as well because the arrangement she chose for This Little Light of Mine also had a cello part.

The ensemble and Dr. Harrell sang This Little Light of Mine, with Dr. Harrell playing piano and Wolfe playing cello. The ensemble was also included in performing Steal Away to Jesus, a spiritual that Dr. Harrell chose to include because it was described in Of the Sorrow Songs. She explained the double-meaning of “steal away” for enslaved people, meaning both spiritual liberation and escape from slavery.

Singer Miyani Mercer found the experience particularly impactful. Performing with Dr. Harrell gave her an opportunity to improve her confidence in choir.

“I enjoyed [performing] because I got out of my shell,” she said. “I’m a good singer but I’m very shy.”

The final song Dr. Harrell performed for students was the piano piece Troubled Water, which is based on the spiritual Wade in the Water.

The music Dr. Harrell performed was only a small portion of all the spirituals that exist to sing and study. She provided students with a list of the 136 songs cataloged in the 1867 book Slave Songs of the United States.

“It resonated with me how many songs were in the book,” junior Camille Gill said. “I didn’t know there were that many, and it was good to hear them and know they existed.”

Dr. Harrell left students with a more thorough understanding of what Negro spirituals are and where they come from, while also showcasing other students’ talents and the significance of this rich source of American heritage.

“These songs are for everyone, they’re not just for the African American community,” she concluded. “Everyone should know about them and be educated about them…It’s really an American music.”