Fleeing War, Settling in Beachwood

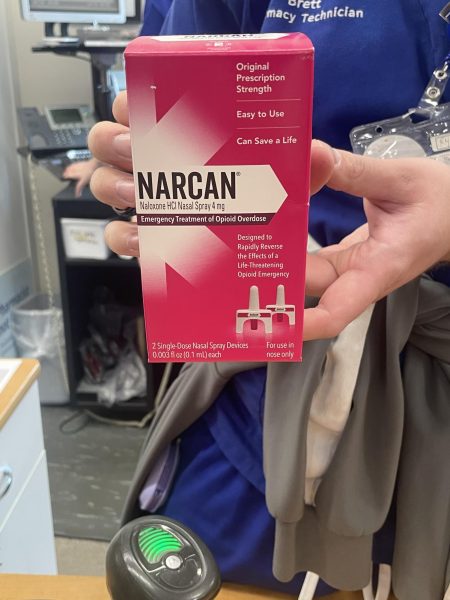

View of The Arch of Freedom of the Ukrainian People from the Glass Bridge in Kyiv.

When news broke of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine last February, junior Yeva Butovska thought about her relatives and friends who were forced to flee their homes without money or a plan for the future.

“[They were] subjected to massive and brutal shelling…” she said. “None of them knew if they would live to see tomorrow.”

Butovska and her family are among the 3,000 Ukrainian refugees who have settled in Northeast Ohio since the start of the war, according to Global Cleveland. A handful of these refugees are now BHS students. They are dealing with the trauma of being displaced by war as their homes were destroyed and loved ones killed.

“Some cities were wiped off the face of the earth,” Butovska said.

Butovska, who was born in Crimea, has seen Russian aggression before. In 2014, Russia invaded and occupied her homeland, a region that had been part of Ukraine since 1954.

“I’m waiting for the liberation of my native land, even though eight years have passed since its occupation. I’m waiting for the defeat of Russia,” she said.

On Feb. 24, 2022, the Russian military began its invasion of Ukraine, targeting cities including Berdyansk, Chernihiv, Kharkiv, Odessa, Sumy and Kyiv, the capital of Ukraine.

According to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, as of December 2022 there have been over 6,800 reported civilian deaths in Ukraine as a result of the war.

The scale of the conflict has displaced more people than any conflict in Europe since World War II.

Butovska had not planned on moving to America. The war changed that. Her family fled Crimea last March, initially moving with her family to France. A few months later they moved to the United States via the green card lottery.

Senior Sonia Razhyk was born and raised in Kyiv, Ukraine. She moved to the United States when she was 12 years old, but visited Ukraine during school breaks. She described the moment she first learned about the Russian invasion.

“I remember getting a text from my friend at 9 p.m. (4 a.m. in Ukraine), ‘We are getting bombed,’ My hands immediately started to shake,” she said. “I didn’t sleep the whole night of Feb. 24. I was texting everyone, even people with whom I was not in contact anymore.”

Since the war started, though, Razhyk has not seen her family or friends for over a year.

So much of the information we get about Ukraine is from the news. But the news doesn’t, or simply can not tell the whole story.

Razhyk explained that the struggle of individuals gets overshadowed by global conflicts unfolding on a world stage.

“The news [doesn’t] talk about the number of pro-Ukrainian civilians who were tortured by the Russians, the number of mass graves, or the raping of women, kids, and elders,” she said.

“The mothers were raped in front of their children, and children were made to watch the rapings.”

Ukrainian forces found a mass grave in the eastern town of Izyum after the territory was recaptured by Ukrainian forces in September.

A U.N. investigation found that Russian troops raped and tortured children.

“The Russian soldiers in Izyum raped an infant with a spoon,” she added. “The women in Ukrainian army forces were captured by Russians and came back with their hair shaved off, which is just a sign of dehumanization.”

Sophomore Kyrolo, or Ky, Babyak is studying in the United States on a scholarship program to which he applied long before the invasion.

After the war broke out, he sought refuge in France with his family. While in France he was notified of his acceptance into the program, and stayed this fall with a host family in Beachwood. At publication, his program is sending him to stay with a different family in upstate New York for the spring semester.

Babyak has been frustrated by the ignorance he has encountered, and he has made it his goal to correct misconceptions.

“I wish people knew the difference between Russia and Ukraine,” he said. “I wish people at least knew that Ukrainian is a language.”

“I don’t really get mad, because as long as I’m not told that it’s not a real language, I will put my effort into explaining the truth to them,” he added. “You have to break the chain of aggression, of being frustrated.”

He wants Americans to examine their assumptions about Ukraine.

“There’s a big misconception with our country being poor or uncivilized,” he said. “[I want to ask people,] How do you know that? Did the movies tell you that? Did the books tell you that?

In spite of the horror Ukrainians students have witnessed unfolding in their home country, Babyak and other Ukrainian students are committed to returning home.

“The one big question you will ask a Ukrainian person: Do you want to ever go back? Most probably they will tell you, yes,” Babyak said. “They are not telling lies. They’re telling the truth.”

Butovska encourages students to learn more about the conflict and spread awareness on social media. She particularly recommends two English-language Instagram accounts: ukraine.shortly and ukraine.ua. She also encourages people to donate to support Ukraine: https://war.ukraine.ua/donate/

“To be on the side of Ukraine now is to be on the side of truth, honor and freedom,” she said.

Samah Khan (she/her) started writing in the fall of her sophomore year in 2020. She enjoys covering macroscopic world issues and their impacts on the Beachwood...