Motivation: How Does it Work?

As the school work picks up pace, it can be hard to keep motivated.

As we approach the culmination of the first quarter, students might start to feel overwhelmed at how courses are picking up pace, how homework seems to be more time consuming, or how club meetings seem to have started during the same week as unit tests.

This period can undoubtedly be stressful. With full in-person classes and changes to the bell schedule implemented this school year, adjusting can be a challenge.

Kaajal Krishnan feels stressed by senior year.

“Senior year is definitely making me slack off,” she said. “Senioritis is making everyone feel like applying to college, going to college and getting out of high school is it. So I’ve definitely felt unmotivated thus far.”

Some students, however, don’t feel their enthusiasm fluctuating.

“Personally, my motivation has not decreased this far in the school year,” Freshman Lyndia Zheng said. “I still have the adrenaline that comes with the school year starting, and I’m really excited for extracurriculars,”

What’s dividing these two groups of students, and how can they bridge the gap in order to maintain a steady flow of productivity?

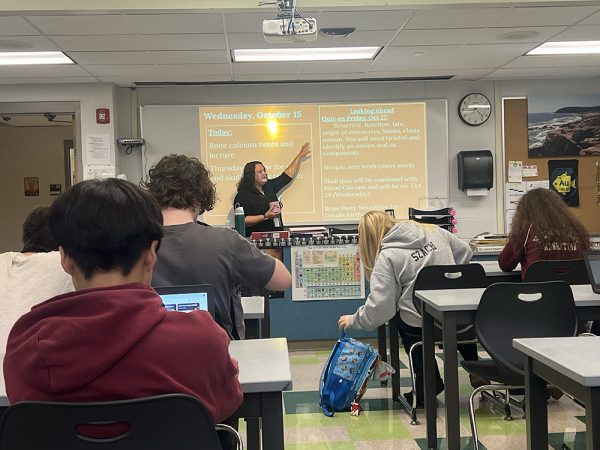

Conveniently, Dr. Casey Matthews has been covering a unit called ‘Drive’ almost every year in her Honors English 9 class, and in it, she covers different types of motivation, healthy and unhealthy sources of motivation, as well as the psychological reasons humans rely so greatly on this intangible feeling in order to accomplish their goals.

Matthews says the key to creating a positive sense of motivation in the classroom is to involve the students and make them feel welcome every time they walk in.

“I think creating a system where the students feel they are part of the classroom community and believe the teacher is there to support them gives them motivation to learn,” she said.

Guidance counselor Jason Downey also believes that student-led goals are easiest to reach, no matter what they are.

“[What increases motivation is] setting goals, big or small, whether they are academic like trying to get better grades than last year, or socially, like trying to be more involved and make new friendships,” he wrote in an email.

Junior Charlie Greene sets up reward systems to push herself to complete assignments and help her focus more on the present.

“[I look] to my future and find little, everyday things to look forward to, because it drives me to do better,” she said.

Similarly, according to an article published in the New York Times by Shaker Heights psychologist Lisa Damour, motivation is nurtured in situations where students feel more autonomy and freedom in the strategies they use to solve problems, study for tests, or even just to get through the day’s homework.

This emphasis on autonomy leads to an important distinction between two types of motivation: intrinsic and extrinsic.

“When what we’re doing feels fascinating, such as reading a book we can’t put down, we’re propelled by intrinsic motivation; when we pay attention in a class or meeting by promising ourselves 10 minutes of online shopping for seeing it through, we’re summoning extrinsic motivation,” Damour writes.

Intrinsic motivation is the drive that comes from within oneself. It is the fuel that is needed to sit down at a desk after six hours of school only to spend three more hours on homework. It’s often supplemented by external rewards, like taking a 10-minute break after every assignment, or internal rewards, like congratulating oneself on a job well done.

However, pure, uninfluenced intrinsic motivation is what professionals call, “Flow Theory”, or the act of voluntarily dedicating oneself to a particular task that one enjoys performing. It provides a sense of mastery and control in the involved activity, which is where humans thrive the most and are most productive.

Matthews tries to harness this sort of motivation by allowing her classroom to be that space for students to express their untainted passion and creativity.

“The students know that [when] they come in, it’s always going to be a positive environment, which I think really helps decrease anxieties,” she said.

Greene agrees that environment can have a big impact on motivation.

“ When people around you are excited, it makes you want to be excited, too,” she said. “And if you’re excited, you want to work more.”

Extrinsic motivation comes from outside sources rather than inside oneself. It’s the salary from a part-time job; It’s the CVC trophy; It’s the college acceptance letter. Extrinsic motivation can be physical, verbal, or even emotional, such as another person’s pride in you.

However, extrinsic motivation can backfire. Using strategies that involve the classic ‘carrot-on-a-stick’ method doesn’t engage one in the same way that intrinsic motivation does.

When following a carrot on a stick, the path beneath is often overlooked. Rather, the central focus is on the carrot. Likewise, having an external reward for a task may inhibit a student’s ability to grow, or actually experience the benefit of learning from an assignment. While extrinsic motivation can be useful at times, it’s best to avoid using it in the long term.

Matthews highlighted a common phenomenon of motivation in the school environment.

“We have what we call the February slump,” she said. “As you know, motivation usually increases right around the quarter, [when] grades are coming out. You definitely see different times of the year when students are just tired, and we get that.”

The ‘February Slump’ is experienced by educators as well. Once the weather gets dreary and cold, it is difficult even for teachers to continue teaching every day with the same enthusiasm projected to students, the majority of whom would have rather stayed home and slept in that morning. It’s important for students to recognize and appreciate that our teachers are human, too.

“I think just acknowledging [struggle] is really important,” Matthews said. “To say this is really hard, this is a tough time right now, we’re all here, and here’s why we still have to do this– gives purpose when it seems like there isn’t.”

However, it’s crucial to take some kind of action. Re-organizing your study space, making a new schedule, or even altering your environment in the slightest manner can make a difference.

“Students who procrastinate and do not have healthy routines stress and flounder when the workload and daily tasks get too rigorous,” Downey said.

Greene advises classmates to stay calm.

“Don’t be emo, don’t be sad, and don’t stress yourself out,” she said.

All this information may be interesting to some, but it’s crucial to identify ways to implement it into our daily lives. It doesn’t even need to be complex. When sitting down to complete an assignment, it would be beneficial to note: What’s pushing them to do this? What kinds of rewards work for them? And most importantly, why are they doing this? Understanding ulterior motives for even simple activities can help us see the bigger picture more frequently in order to stay on track.

Downey sums up what action students need to take to propel themselves towards success.

“Success and motivation all start with each individual student finding worth and owning it,” he said. “If a student has goals and has a healthy lifestyle like I mentioned above they will be set up for success and our staff will help support [their] progress.”

“It will not happen overnight though, students have to be dedicated to a lifestyle routine to find continued success,” he added.

Regardless of the challenges that students face in the return to a semi-normal school year, fostering a consistent stream of motivation is key to academic success. And, eventually, though, students who propel themselves forward in spite of the odds will get their carrot.

Anah Khan (she/hers) started writing for the Beachcomber in 2021. She is interested in covering new organizations and programs in BHS and writing opinion...