Hear Them Roar

In honor of Women’s History Month, the Beachcomber presents 10 women who changed the world

In the 1880s, Nellie Bly pretended to be mentally ill in order to report undercover on the appalling conditions in the insane asylum on Blackwell’s Island. The New York World published her six-part series, a pioneering work of investigative journalism.

Sybil Ludington (1761-1839)

Sybil Ludington’s father was a Colonel in the American army during the American Revolution, and when a messenger stopped by their house to warn them of an attack on Connecticut, Ludington rode 40 miles to spread the news to the army men. She is known as the female Paul Revere, but rode 27.5 more miles than Revere at 16 years old, according to the Journal of the American Revolution. She is on a stamp, has a statue in her honor in Carmel, New York, and her riding path is marked by historical markers.

Clara Barton (1821-1912)

Clara Barton founded the American Red Cross. During the Civil War she was a nurse to Union troops. She paid for a lot of the healthcare expenses during the war either with her own money or through donations. She was also the General Correspondent for the Friends of Paroled Prisoners and worked to help families of missing soldiers by searching for them. She found 22,000 missing soldiers. After the war, she traveled abroad, learning about the International Committee of the Red Cross founded by Swiss humanitarian Henry Dunant in 1859. Barton was inspired to found the American Red Cross, becoming its first president.

According to the Clara Barton Museum she once said:

“I may sometimes be willing to teach for nothing, but if paid at all, I shall never do a man’s work for less than a man’s pay.”

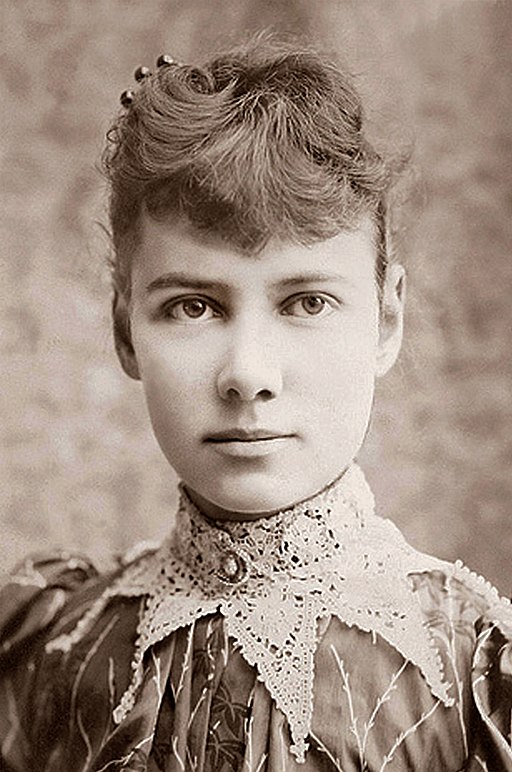

Elizabeth Jane Cochrane Seaman (1864-1922)

Also known as her pseudonym Nellie Bly, Elizabeth Jane Cochrane is most known for her 72- day solo trip around the world, according to the Library of Congress. Seaman started reporting at age 16, and while working for the New York World, was given what may have been her most important assignment: infiltrating a mental hospital to see the conditions with which they treat the patients. When her report on mental hospital conditions was released, she made waves raising awareness about the mistreatment of patients and abuse of immigrants. Some of the improvements made to mental hospitals as a result of her work include hiring translators for foreign speakers, offering better meals to hospital patients and improving cleaning services.

Daisy Bates (1914-1999)

Daisy Bates knew racism at an early age; she saw her mother murdered by white men when she was just a child. This incident is what led her to the path of activism. Alongside her husband, she published a pro-Civil Rights newspaper in Little Rock, Arkansas in the 1940s. She was also one of the NAACP’s Arkansas chapter’s Presidents and was influential in the struggle for integration. Bates also selected the students who would integrate the Little Rock schools, drove them to school, kept the Little Rock Nine safe from white protestors and wrote an award winning book about it. As part of the Johnson administration, she combated poverty. She lived her life fighting for others despite the threat it meant to her own life with segregationists incessantly attacking her. She was also awarded a Medal of Freedom after her death and Arkansas has Daisy Gatson Bates Day (third Monday in February).

Satoye Ruth Hashimoto (1913-2010)

Satoye Ruth Hashimoto was held in an internment camp during WWII because she was Japanese-American. While in the camp, Hashimoto organized a school and organized activities for the interned. She was released early in order to teach at the Navy Intelligence Language School. After the war, Hashimoto continued teaching and helped translate for Japanese immigrant families and school officials. She also helped others pass the citizenship test and taught English. She was inducted into the New Mexico Women’s Hall of Fame, and was given the Japanese American Citizens League Humanitarian Award among other achievements.

Margaret Hamilton (1936-)

Lesser known than Neil Armstrong, Margaret Hamilton was essential to putting a man on the moon. She was director of a lab at MIT that designed the onboard software for the Apollo missions. She was also the first female software engineer working on the Apollo project. Even when more came to join, they were always outnumbered by men. Despite all that, Hamilton led the team of software engineers and focused on rigorously testing the programs they wrote. It paid off, in fact, because when an error occurred on the mission, the tests the team did ensured the software would override computer problems and get the men to the moon. In 2003, Hamilton earned the NASA Space Act Award due to her work which was fundamental to software engineering. Her award also included the largest financial award ever given by NASA. In 2016 she was also awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Obama.

Mae C. Jemison (1956-)

Mae Jemison, who went aboard the Space Shuttle Endeavor, was the first African-American woman in space (1992). After graduating as one of the only African-American students at her high school, she continued studies at Stanford and then at Cornell Medical College. She worked as a doctor at a Cambodian refugee camp as well as in the Peace Corps before pursuing work at NASA. After six years at NASA, she founded her own company, created a nonprofit, wrote a book and is now working on a research project dedicated to star travel and serves as Board Director on multiple organizations. Jemison is in the National Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Medicine, the National Women’s Hall of Fame, National Medical Association Hall of Fame, Texas Science Hall of Fame and has been awarded many honorary doctorates and awards, including the Kilby Science Award.

Shirley Chisolm (1924-2005)

A legacy of firsts: Chisholm was the first woman to run for the presidential nomination for the Democrats, first African American to run to be the presidential nominee of a major party, campaigned for a potential first African American judge in Brooklyn, first African American woman in Congress and was first African American woman to serve on the House Rules Committee. She was a founder of the Congressional Black Congress, one of the founding members of the National Women’s Political Caucus and co-founded the National Congress of Black Women. She also helped pass the minimum wage bill in 1974, was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame, is on a stamp and was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom. During her run, she was not able to secure support from minorities and women because she was a woman and a minority. That is, some men of color didn’t support her for being a woman and some women didn’t support her for being Black. However, she was supported by Black women. Even though she didn’t win, Chisholm’s run for presidential nominee made ripples in society and paved the way for the future. In fact, her winning wasn’t what she focused on. Instead, used her run to divide the votes and give her political capital to barter with other candidates. She proposed dropping out of the race in exchange for an African American vice president, a woman in the cabinet and a Native American as Secretary of the Interior, but was refused.

According to the Smithsonian, Chisholm once said, “I want history to remember me… not as the first Black woman to have made a bid for the presidency of The United States but as a Black woman who lived in the 20th century and who dared to be herself. I want to be remembered as a catalyst for change in America.”

Selma Lagerlöf (1858-1940)

Selma Lagerlöf was the first female and first Swedish winner of the Nobel Prize of Literature. Lagerlöf was inspired by her grandmother’s fantastical tales and historical retellings of Sweden’s past. Lagerlöf worked as a teacher when she published her first books. But when she earned a fellowship from the Swedish royal family and a scholarship from the Swedish Academy, she quit her job and traveled the globe. She used her earnings from the Nobel Prize to buy back her family home and donated her medal to support the fight against the Soviet Union in WWI.

Pura Belepré (1899-1982)

If you’ve ever been in the library and seen a book in Spanish, that would be thanks to Pura Belepré. She was the first librarian of Puerto Rican descent to work in New York’s public library system. In fact, she may have also been the first Afro-Puerto Rican librarian in the continental United States. Belepré noticed the lack of Spanish children’s

books in her Harlem library, so she wrote her own.

Her book, The Tiger and the Rabbit, was the first Puerto Rican folk-tale published in the United States. She would also do puppet shows in English and Spanish for her young audiences. Now, there is an award given to Latino authors and illustrators whose books are for children and young adults, according to NPR.

Hiba Z. Ali began writing for the Beachcomber in fall of 2019. She covers diversity in the school. In addition to writing for the Beachcomber, she also...