Canned food drives, the jingling bells of salvation army workers and soup kitchens are as much a part of the holiday season as Hanukkah candles, Christmas trees and neatly wrapped presents.

While many focus on giving and volunteer service exclusively during the holiday season, community service is an issue that BHS students think about more often than most in order to achieve the 50 required hours for graduation and to fulfill the district’s mission to produce “entrepreneurs with a social conscience.”

But just how much is community service a part of the collective student conscience? For some students and staff, Beachwood is a community of civically-minded youngsters. Yet for others, the ethos of BHS leaves something to be desired.

The first issue is the civic character of the student body. Some, like sophomore Saige Eitman, social action vice president of her temple’s youth group, see this character as lacking.

“People in Beachwood are kind of in their own bubble, and they don’t realize there are so many other people who are less fortunate than we are,” she said. “I feel like people at Beachwood think that they’re at the top of the world and there’s nothing else out there.”

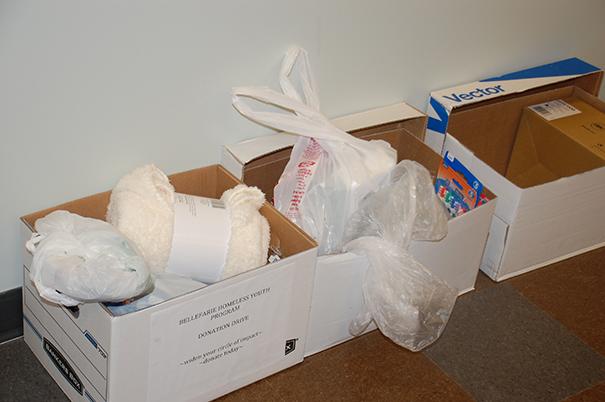

Others, like English teacher and leader of the homeless teens drive Casey Matthews, say the opposite. “It’s just a generous population. Beachwood is just an amazing place because they do care,” she said.

“The kids here, they’re interested in other people,” said senior and Amnesty International co-president Esme Eppell.

“Once they know what’s going on, or once they’ve got the message through to them, I think they’re eager to help, volunteer, whatever it is. I think it’s just about getting the foot in the door,” she elaborated.

Some also question the 50 hours of community service requirement as a means of instilling a social conscience. Some feel that hours are plenty, while others see them as insignificant.

“I know a lot of students have a lot on their plate, trying to keep up with grades and some of them have jobs outside of school. I think 50 hours is an amount most students can handle and they still get to see hopefully the benefit of volunteering their time,” said National Honor Society adviser Amy Hazelton, on the pro-requirement side. Service is one of the five “pillars” (or key values) of NHS, and service hours are a prerequisite and an ongoing duty.

“Some people don’t have time, they’re really busy with other things, so I think 50 hours is fair,” said Eppell, echoing Hazelton’s sentiment.

Yet others think it’s not enough, like freshman Inkyu Kim, who is very involved in Teen Court. “The more [hours] we have the more we can do to make a bigger change,” he said.

Still others disagree with the idea of a requirement entirely. “I don’t think we should have a requirement. I think people should help because they want to help. If you force someone to do it, they’re not going to want to do it, as much. That being said, with a requirement, I guess that’s a way to get kids started,” said senior and Amnesty International co-president Danny Padilla.

“If kids don’t want to volunteer, they’re not going to volunteer, regardless of the requirements. They’re not going to really benefit hospital patients or the elderly if their hearts not in it,” elaborated Padilla.

Actually, BHS does measure up favorably when compared to other local schools. The programs of studies of many local public schools do not list community service as a graduation requirement.

A third concern some have with the volunteer requirement is the actual kinds of volunteering students are doing. Some feel students complete their requirements with less-than-meaning- ful activities, while others feel that any kind of volunteering benefits the community.

Hazelton is of the opinion that students could do more meaningful activities to fufill their requirements as National Honor Society members. “I would like for NHS members to start doing more meaningful activities that will affect the community as a whole,” she said.

Eitman also feels that students fill their requirements with substandard volunteering. “I think the 50 [hours are] great, but I don’t think kids know what to do with it. I think they [only think to] volunteer at a camp for kids who are paying a couple hundred dollars,but you’re not making a difference when you do that,” she said, referring to BHS students who volunteer at paid camps for affluent children. “You’re just a face to a little kid’s summer.”

Others don’t believe that the kind of volunteering can invalidate the experience, like Padilla. “Volunteering is volunteering,” he said.

A last concern is that students are ignorant of volunteering opportunities. Would students choose more meaningful activities if they had more knowledge? For Kim, the answer is yes. “The biggest problem is that many students don’t know where to go, so they just go with their family’s company, and don’t do something that would help the com- munity,” said Kim.

“I think most kids dread [volunteer hours] because it’s just something else they have to check off,” said Matthews. “But if you find the right organization, and there are a million organizations, then it’s going to be fun. Find something that you like, find something that interests you, find something you’re passionate about, and get involved.”

Others don’t see this lack of knowledge as an issue. “I think our school does a good job telling what the volunteer opportunities are and what they can do,” said Eppell.

Whatever the level of commitment, there is agreement that volunteering is something students should do.

“If you’re not involved in an organi- zation that [does] volunteer work, unless your parents [haven’t] taken you [volunteering], I think it’s important for the school to take that role on and require students to do some volunteer work,” said Hazelton.

The importance of volunteering becomes especially relevant in an affluent community like Beachwood. “We’re so blessed, we live in Beachwood, we have so many extra things,” said Eppell. “There are some people out there who don’t have those privileges so it’s nice to be able to help them.”

“It’s nice to give back. Especially in Beachwood, we have so much, it just seems a little narcissistic to not give back,” said Padilla.

“It’s a way to get people to realize that not everyone has two cars, a fridge full of food every single day. The reality is that most people don’t have–they don’t get cars when they’re 16. And I think by volunteering, especially in lower income areas, you realize that because you see it first hand,” Padilla elaborated.

Matthews sums up this spirit: “My life does not end at my front door, it’s not wrapped in my house, it’s not wrapped in my drive to school. I volunteer because I can, because I should, and because I need to.”