With high-achieving students, Beachwood has a reputation as a regional landing pad for helicopter parents. However, students, parents and staff feel that the issue is much more complex than it may seem, and that parent involvement has positive as well as negative consequences.

The term ‘helicopter parent’ refers to overbearing parents who are extremely involved in their children’s lives, thus hindering independence. “Helicopter” behavior describes sideline coaching at sporting events, checking eSIS daily, or giving college-aged students wake-up calls so they come on time to class.

Dr. Patricia Somers of the University of Texas spent a year studying the species, and estimates 60% -70% of today’s parents are “helicopters.” She also observed that overbearing parents breach all racial, ethnic and socioeconomic strata.

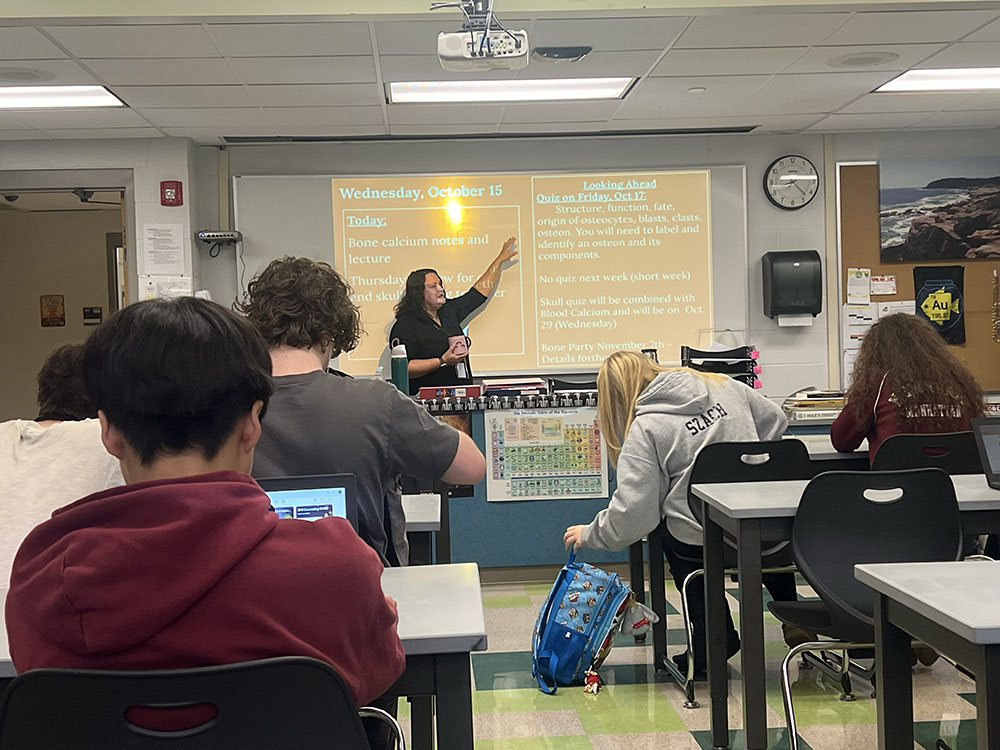

In Beachwood, perhaps the most apparent aspect of hovering parents can be found in over-committed students, suggested Melissa Buddenhagen, social studies teacher and a mother to three children.

“You want them to have enriching activities and varied interests so you don’t give them time to just be,” explained Buddenhagen. “Having heavily-scheduled kids is a big thing here. That’s not a bad thing, it can just be tough for kids to decide what they really like and what they want to do with free time.”

English teacher and father Peter Harvan elaborated on the definition. “I guess you don’t need to be literally hovering over a kid to be a helicopter parent. If you dictate their life by organizing every minute of their time, then that’s a form of helicopter parenting too,” said Harvan.

School psychologist Kevin Kemelhar explained the ramifications of this parenting style, noting that it can result in strained relationships between parent and child.

“It can hinder the relationship parents have with their kids and it can hinder other people having a positive affect on their kids: teachers, coaches, physicians and so on. Those kids are at risk for negative relationships with their parents, and at risk for stress,” said Kemelhar. He also noted that this style can hamper adolescent development. Children of helicopter parents will not develop independence at the same rate as others.

“A lot of times [these kids] are really good students,” said Buddenhagen. “The issue is that they don’t have the ability to solve their own problems…They don’t want to have any discomfort.”

Helicopter parenting can have positive and negative effects. Assistant Principal Paul Chase focused on the positive.

“Parents know what pressures are…out there,” said Chase. “I think when you talk about pressures, the expectation of a parent is to know that the kid is trying his hardest, and Beachwood parents are very knowledgeable about what their sons or daughters need to do in order to succeed.”

Some students also agree that invovled parents can be helpful. Sophomore Tyler Thomas believes it a parents’ primary job to encourage kids to succeed, not be their friend. “If your kids don’t like you but are doing everything right, you’re a good parent,” said Thomas.

As for students who do have overbearing parents, Guidance councelor Carolyn Beeler said, “We see kids step up and take ownership for themselves. They can earn their parents’ respect, and prove that they can make good decisions. At the end of the day, if the child isn’t ready to go and a parent knows that, the parent may encourage their child to stay closer to home.”

Dr. Erica Remer, the mother of Yale-bound Presidential Scholar Scott Remer, explained what she thinks is most important in parenting effectively.

“You should encourage your kids’ passions,” said Remer. “Be a good listener. Ask them their opinion. Talk to them like their opinions matters. Praise their successes, comfort them when they fail, but make sure they understand that is part of life.”

Because of the fine line between concerned and overbearing parents, answering the prying question as to whether or not Beachwood parents are flexing their propellers can be tough. Staff and administrators mostly emphasized that parents here are not overbearing or unsupportive of decisions made by school staff. In fact, Chase, Harvan and Buddenhagen all agreed that they rarely receive calls from parents.

Remer, who has been actively involved in the schools, said, “I think Beachwood has some demanding helicopter parents, but the parent who is uninvolved and doesn’t help a child achieve his potential can be even more detrimental. When I volunteer in the schools, I see lots of kids who need more guidance and parenting and care than kids who are being harmed by hovering parents.”

Nevertheless, what was most prominent among parents, teachers and students alike was the collaborative approach of Beachwood. “For the most part, kids want to do well, and give effort,” said Kemelhar, and adult figures at Beachwood seem to honor this.

Elizabeth Gloger, parent of junior Elana Gloger, explained, “My approach is collaborative. I am not a teacher – it’s not my place to tell them what to do in their classroom. What I can do is give them more information about my child, which might help in their understanding of a situation, and help us together find a way to make things better.”

Beeler agreed that students at Beachwood are surrounded by a team of support networks. “I like to see parents and counselors and teachers and administrators as part of a team. We’re all on the same team to help kids be successful.”

Perhaps the essence of the hovering mentality is captured by Buddenhagen’s observations. Whether parents are too demanding or need to be more present, she’s observed that at the end of the day, there is room for school-parent collaboration in child-rearing.

“I’ve never found that teachers and parents are on different teams, said Buddenhagen. “The students, teachers, parents are all on the same page. That’s all anybody wants: the best outcome for students.”

![“My parents have always said that education is important. My parents are Chinese immigrants, I'm Chinese American, [and that's a] value that has always been ingrained in our community,” said Senior Lyndia Zheng, pictured with Tony Zheng](https://bcomber.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/DSC_4244.jpg)