I have never seen the effects of opioids up close, so I never thought I’d find myself at multiple pharmacies in the Cleveland area asking, “Do you carry Narcan?”

But that’s exactly what I found myself doing this summer while participating in the Naloxone Accessibility Challenge, an initiative coordinated by SAFE Project, a nonprofit focused on ending the addiction fatality epidemic through prevention, recovery and community action.

Participating in the challenge gave me the opportunity to investigate how accessible the life-saving medication naloxone really is in our community and beyond—and what I found surprised me.

As a member of SAFE Project’s Youth Voice Council, which brings together high school students from across the country to address the addiction fatality epidemic through shared solutions, I helped assess the accessibility of the overdose-reversal medication naloxone in our community.

This includes surveying locations such as pharmacies, harm reduction centers, retail stores and even public places where AED kits are typically mounted.

The importance of this is clear when considering that opioid overdoses remain a leading cause of death in the United States.

In 2023, there were more than 105,000 drug-involved overdose deaths nationwide, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and 4,452 unintentional drug overdose deaths in Ohio, according to the Ohio Department of Health. Cuyahoga County was hit especially hard, recording 635 deaths that year, according to the Cuyahoga County Board of Health.

These numbers reflect the deadly speed of opioid overdoses: when a person overdoses, the drugs slow or even stop their breathing by binding to receptors in the brainstem, which can cause death within minutes if left untreated.

To counter this, naloxone is a medication that can reverse the effects of an opioid overdose by restoring normal breathing to a person who has overdosed. It works by attaching to opioid receptors in the brain and blocking the effects of opioids, but it has no impact if opioids aren’t present.

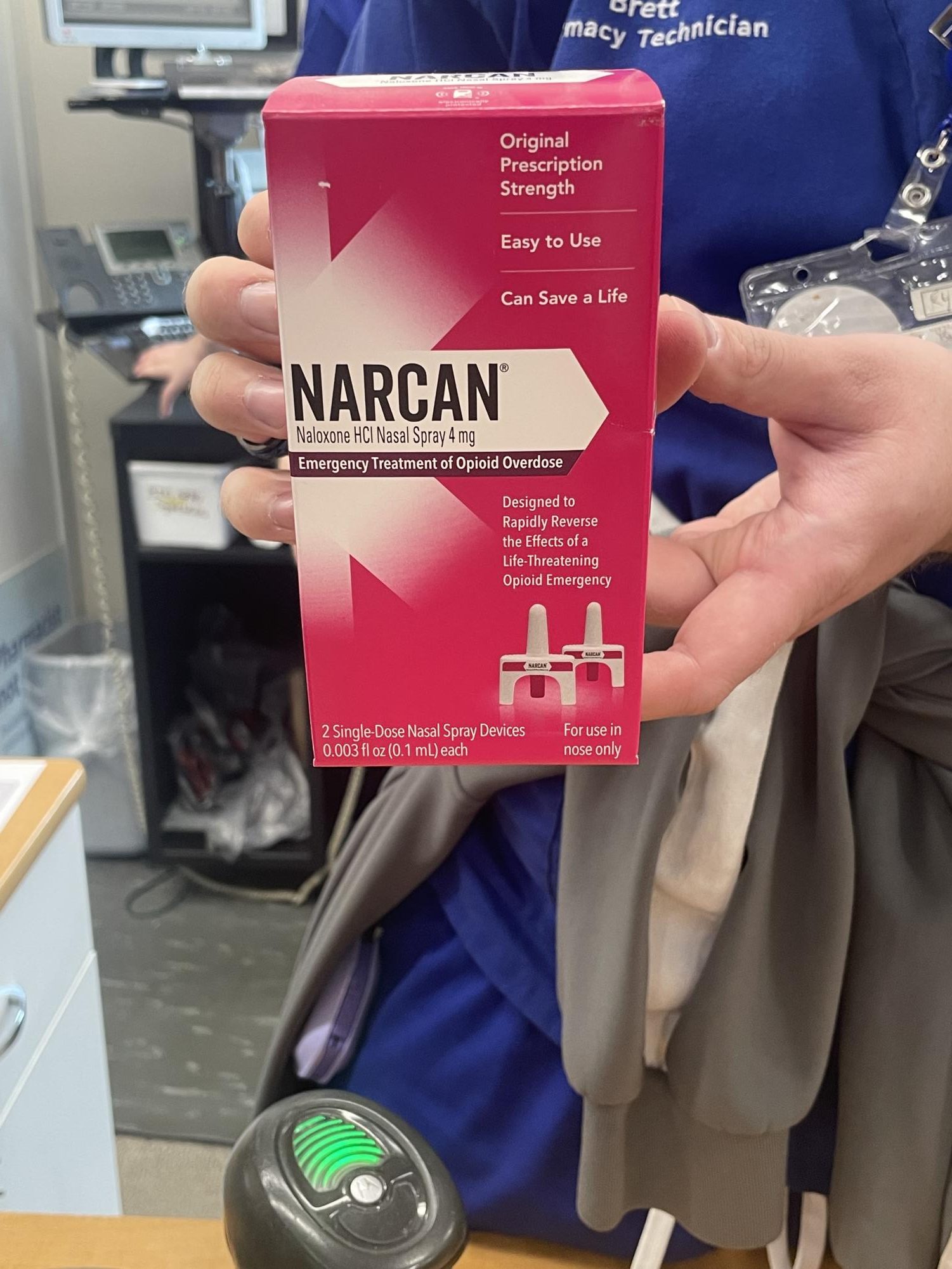

It’s most commonly available as a nasal spray called Narcan.

While it is approved for over-the-counter sale, access remains uneven–especially due to its high price.

Greater accessibility is not just a matter of convenience; according to a 2025 systematic review and meta-analysis published in the National Library of Medicine, community naloxone distribution programs can reduce overdose mortality by approximately 25-46 percent.

I began my journey by visiting major chain pharmacies such as CVS and Walgreens in the Cleveland area, including locations in Woodmere, Lyndhurst and Cleveland Heights. In total, I visited seven CVS pharmacies, and fortunately, all of them carried Narcan over the counter.

Each box, containing two single-dose nasal spray devices, was priced at $44.99.

In some stores, Narcan was located in the aisles near the pharmacy, in a variety of sections, including: the vitamins/feminine care/family planning aisle, the adult nutrition/diabetes care/home testing aisle and the allergy relief/cold & flu/cough drops aisle.

When Narcan was not readily available on the shelves, I had to go up to the pharmacist and ask for it; most of the time, they knew where it was located: behind the counter.

However, I had an interesting experience in one of the CVS pharmacies I visited. I couldn’t find Narcan in any of the aisles, so I asked the pharmacist technician if they carried it. As I was speaking, I happened to spot the familiar bright pink box sitting on one of the shelves behind the counter.

Strangely, the pharmacist technician didn’t notice it at all–he searched behind the counter, passed right by it, and then told me he needed to check the front register for availability. I waited as he walked away, then let him know after he came back that I had seen it on the shelf behind him.

He glanced back, said “Oh,” and finally retrieved it.

While this may have simply been a mishap, I was honestly surprised that I–a high school student–was able to locate a life-saving medication faster than a pharmacy technician.

It made me wonder: what would happen if someone experiencing a real emergency came into that same store? What if a person who had just witnessed an overdose needed Narcan urgently, but the pharmacy technician couldn’t find it or didn’t know where it was?

Naloxone works by quickly restoring breathing, but timing is critical.

According to Narcan, one of the most commonly used brands of naloxone in the U.S., the medication should be administered right away at the first signs of overdose, and additional doses may be given every 2-3 minutes if the person does not respond, while waiting for emergency personnel.

This urgency highlights why easy access is critical in real-world emergencies.

Indeed, this moment made it clear to me that awareness and proper training aren’t just helpful, but can mean the difference between life and death.

On the brighter side, at another CVS location, a pharmacist not only confirmed that Narcan was available, but also shared a QR code sticker linking to free Narcan and fentanyl test strips through an organization called Thrive for Change.

She told me the stickers had been stolen sometimes, which is why she kept an extra one in her car just in case someone needed them discreetly.

On the other hand, I also visited several Walgreens pharmacies in Cleveland, and they all had Narcan in stock, in addition to the Walgreens Naloxone HCl Nasal Spray.

One pharmacist requested my age when I asked about naloxone availability, and when I said I was 16, they replied that I was too young to purchase, which did not make any sense as there is no minimum age requirement to purchase naloxone.

Aside from Cleveland, I also visited multiple different CVS and Walgreens stores in Massachusetts, mainly in the Boston area.

While many of the CVS pharmacies in Boston had Narcan in stock, a few did not or the pharmacist refused to show it to me. One pharmacist wouldn’t even let me take a picture to confirm its availability unless I agreed to purchase it.

I also visited a pharmacy in Cambridge near the MIT campus, where I found a different brand of naloxone–Naloxone Hydrochloride Nasal Spray by Teva–being sold for $130.

The price shocked me. I hadn’t expected an alternative to be that expensive, especially compared to the standard $44.99 price for Narcan that I had seen in many other locations.

One Walgreens pharmacy I visited in Boston did not have naloxone in stock.

However, another location carried both Narcan, priced at $44.99, and the Walgreens Naloxone HCl Nasal Spray, priced at $34.99. Interestingly, both products were placed in the children’s medicine aisle, which felt like an unusual location for an overdose-reversal medication.

In some CVS pharmacies in both Cleveland and Boston, the pharmacist offered the option to obtain naloxone through a prescription. Yet according to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Narcan is now FDA-approved for over-the-counter sale, so this kind of mixed message can create confusion about access–especially since some of the pharmacies that I visited still offered naloxone only by prescription.

One CVS pharmacy located in Newbury street in Boston had a small sign on the shelves in front of the pharmacy counter labeled “Overdose prevention and treatment.” Below it were stacks of informational cards.

One card could be taken to the front checkout or pharmacy to purchase Narcan and potentially receive insurance savings. On the back, it also included instructions on what to do and how to use the product in the event of an overdose.

Another card was labeled “Resources to help with substance abuse” and directed customers to visit SAMHSA.gov for support from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, along with other helpful resources such as FindTreatment.gov, FindSupport.gov and SAMHSA’s confidential 24/7 hotline: 1-800-662-HELP (4357).

Seeing these cards on display felt like a meaningful acknowledgement of the opioid crisis. It was encouraging to see a pharmacy not only offer Narcan, but also take steps to pair it with resources and insurance guidance.

Beyond pharmacies, I visited the Boston Museum of Science while in Boston, not expecting to find naloxone there. However, as I was about to take the elevator, I noticed an Opioid Overdose Rescue Kit mounted on the wall above the AED kit.

It was a NaloxBox, a small, clear box labeled “Opioid Rescue Kit” that contains four doses of naloxone (Narcan). Inside the box was a box of Narcan, an informational card, and instructions with diagrams showing the signs of an overdose to look out for.

Similarly, while I was at the University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center, I came across another kit labeled a LIFEPAK AED kit.

Inside the box were a defibrillator and one box of Naloxone HCl Nasal Spray. Like the NaloxBox I saw at the museum, this kit was also located right beside the elevator.

Overall, these experiences changed the way I see my surroundings. Before this, I didn’t even know what naloxone was, let alone that it could be found in places like AED kits mounted on walls–right next to elevators I had taken countless times.

This journey opened my eyes, and I began to realize that life-saving medications like Narcan are available in more places than I expected, but they’re often tucked away, out of sight.

What stood out to me most was that simply having Narcan in stock at a pharmacy or placed in a rescue kit isn’t enough–people need to know it’s there. Clear signage, awareness and visibility are just as essential as the medication itself–and in emergency situations, they can be the difference between life and death.

If you’re reading this, I encourage you to ask your local pharmacy: “Do you carry Narcan?”

Look around your community for rescue kits.

You never know when having that knowledge might make a difference. Naloxone can save lives, but only if people know it exists and where to find it.

Awareness and simple acts, like asking a question, can be powerful tools in preventing the next tragedy. Change starts with all of us.