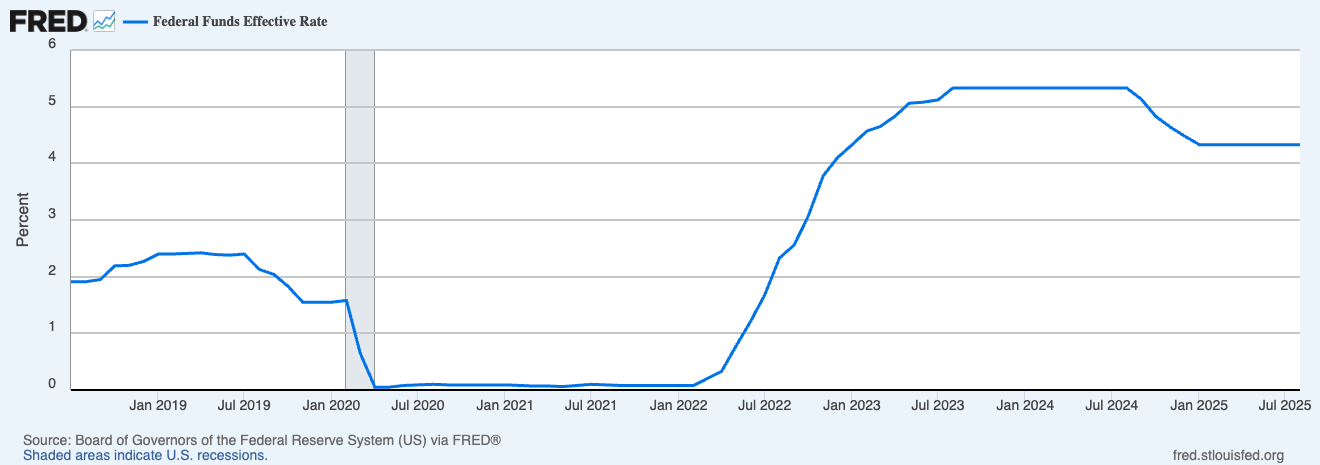

This Wednesday, all eyes are on the Federal Reserve, which is set to announce the fate of the benchmark interest rate—and many are bracing for heavily anticipated rate cuts.

However, with potential inflation and a cooling job market around the corner, is America really ready for slashed interest rates?

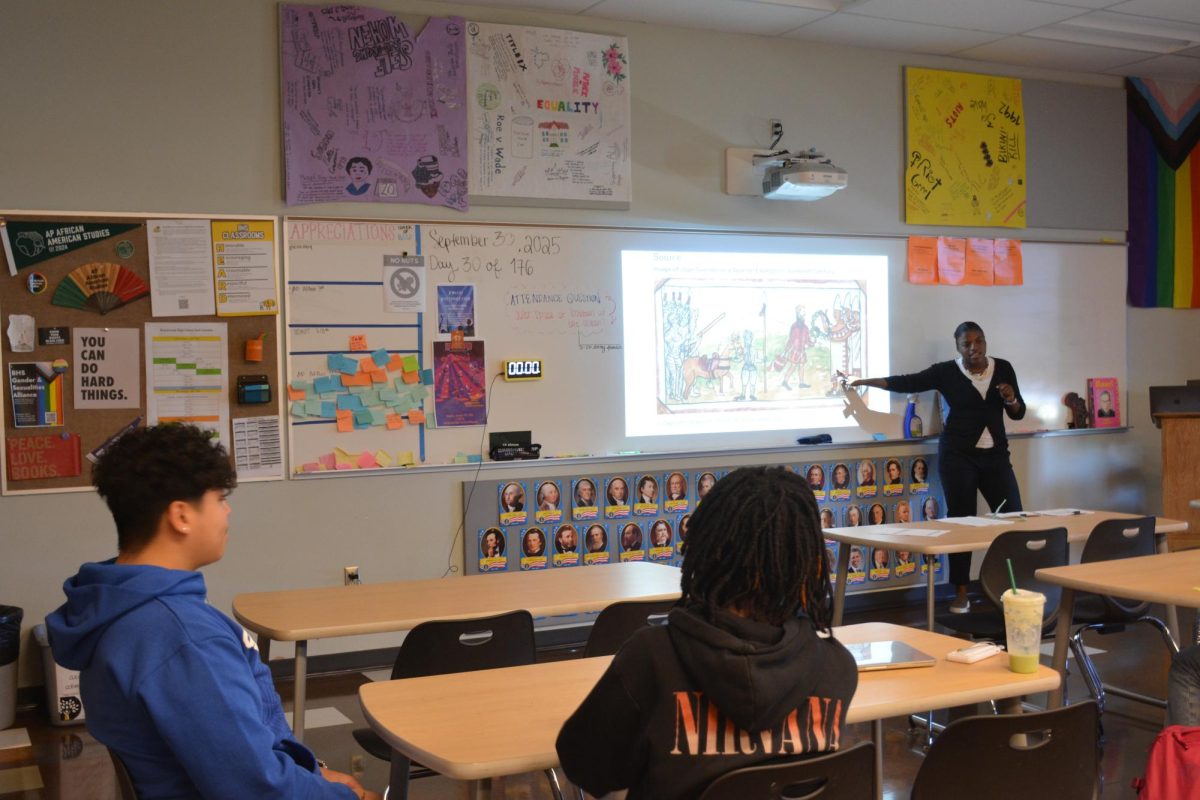

Many high school students don’t know much about the benchmark interest rate or America’s central bank, the Federal Reserve. However, everyone feels the effects of this one rate—including BHS students.

Students with a credit card may recognize their card’s APR (annual percentage rate) or the auto loan their parents pay on their car or the student loans we may take out in a few years: these are all directly affected by the federal interest rate.

The interest rate is officially known as the federal funds rate and is defined by the Federal Reserve as “the interest rate charged by banks to borrow from each other overnight.”

Simply put, the interest rate determines whether interbank loans are cheaper or more expensive. If the interest rate is higher, banks charge more interest on other banks’ loans, and if it’s lower, banks charge less interest.

By determining how affordable loans are for banks themselves, the interest rate can influence how much people and businesses borrow from banks and invest—as though a domino effect; the rates at which banks borrow reserves determine how much money a bank pays, and to maximize profit, the bank passes on the savings or cost to the consumer.

This is why the interest rate is important for most Americans—home loans and other consumer loans are affected by this system, so low interest rates may extend to more affordable financing, and high interest rates may correspond to less affordable financing.

The interest rate also determines where banks invest, as it determines how easily banks come upon money. When interest rates are high, banks may favor safer investments (like Treasury bonds) which offer attractive returns. When rates are low, safe assets tend to yield relatively less, encouraging banks to take on more risk by lending to businesses and individuals.

The stock market reacts similarly: according to BHS math teacher and stock market club adviser John Kaminski, lower rates lift the stock market up.

“If interest rates at the bank are low, say 1%, then the risk of the market seems more tolerable,” he wrote. “[And conversely,] if interest rates are high and you can get a guaranteed 5% return at your local bank then conservative investors, like retirees, will avoid the risky stock market.”

In other words, low interest rates tend to make banks more willing to finance corporate and consumer loans, while high rates can lead to banks prioritizing safer investments over riskier lending. On a macro level, the interest rate influences financing and thus influences whether economic activity grows or slows.

At face value, a low interest rate is desirable—certainly so for the president’s administration, which has put increasing pressure on the Federal Reserve to reduce the interest rate.

Such pressure has gone beyond mere condemnation: the Trump Administration has been widely criticized for its perceived intervention in the Federal Reserve’s deliberation. President Trump even tried to fire Federal Reserve Governor Lisa Cook, a supporter of higher interest rates, over unsubstantiated allegations of mortgage fraud.

Many economists believe that the Fed should be independent from this sort of political pressure. A perceived lack of political neutrality may erode faith in the Federal Reserve as a whole. In an economic recession, this could prove disastrous and fuel mistrust that undermines the Federal Reserve’s ability to influence the economy.

Undoubtedly, there is a faction of those who strongly support a low interest rate. In the Federal Reserve Open Market Committee (FOMC), that faction has been unsuccessful in achieving their goal for quite some time.

In fact, for five consecutive FOMC meetings, the consensus has been to keep the interest rate unchanged from the range of 4.25% to 4.50 set by the last rate cut in December of 2024.

There has been good reason for these rates to be held steady—the Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell expressed the Reserve’s wariness of current inflation which has remained over their 2% target and potential inflation from tariffs.

AP Macroeconomics teacher Pamela Crossman explained that there are risks to cutting interest rates.

“Cutting interest rates would result in increased spending (especially on big-ticket items like homes, cars or anything one would need to finance through a loan,)” she wrote. “[This] only drives prices further up… too many dollars would be ‘chasing’ too few products.”

Crossman drew parallels to the 1970s. A potential rate cut could again induce higher inflation alongside high unemployment, a phenomenon known as ‘stagflation.’

Nevertheless, the Fed may consider a rate cut in order to address unemployment.

“I think some recent poor jobs data is probably the biggest factor in any decision to cut rates this week,” Kaminski said.

The Federal Reserve does not take unemployment lightly: it was assigned the dual mandate of keeping inflation and unemployment in check.

Labor data has indeed, in recent months, proven relatively low, and a lower interest rate could increase economic activity and subsequently increase employment.

Weighing both unemployment and inflation would “require solutions that run afoul of one another” as Crossman put it—the former would require lower interest rates, while the latter would require higher interest rates.

Though not directly stated in the dual mandate, the Federal Reserve may also consider what a change in the interest rate may do to the U.S. dollar.

According to Kaminski, a rate cut would weaken the dollar, which would have pros and cons.

“It could increase exports as U.S. goods become cheaper overseas and help U.S. manufacturing,” he wrote. “On the downside, a weak dollar can make the U.S. less attractive to investors.”

U.S. manufacturing growth has been a point of emphasis for the Trump administration; it has earned mixed reactions for having imposed tariffs with the stated goal of supporting domestic production.

Further supporting this goal is the administration’s decision to make permanent their previous tax cuts for employers as part of a broader tax reform. From a supply side perspective, an interest rate cut would be a logical next step.

It is also true that inflation is a concern, but not as much as in recent years. As of Aug. 31, inflation was 2.9% (in a year-over-year interval), compared to a 9% peak in the summer of 2022.

This does not eliminate the inflation that has accumulated over many years, but it does put in perspective why a focus on employment may take precedence over inflation.

The Fed has a tough decision to make; there are merits to both lowering and maintaining the federal funds rate. There will almost certainly be debate and dissent among proponents of each perspective.

Rate cuts are finally on the table, and with both external pressure from the Trump administration and internal pressure from committee members, the federal funds rate may finally be cut.

Economists confront both inflation and unemployment—to that end, it may perhaps be more beneficial to let the Federal Reserve confront inflation first, finishing the threat once and for all. Rate cuts may be imminent, but perhaps postponing them would be for the better.

Somali Ghosh • Sep 16, 2025 at 8:24 PM

Love the insights in this article!