The Anxiety of Being Asian-American

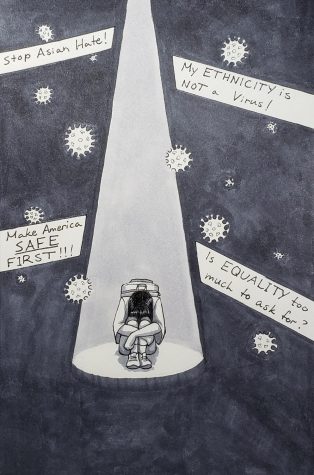

I am not the virus

After President Trump dubbed Covid-19 the ‘Chinese virus’ last year, The Asian Pacific Policy and Planning Council announced that more than 673 cases of discrimination against Asian-Americans were reported in one week.

The eyes express what the tongue cannot; they are intricate organs that allow us to see the world’s beauty and into other people’s souls.

And yet the external appearance of our eyes can also create the illusion of difference.

My beautiful almond-shaped ‘swallow-tailed’ Asian eyes mark me as different, and have led me to be subject to racism.

It was the first day of my seventh-grade year, and I had just moved to Beachwood from Las Vegas. I remember looking in the mirror that day and reminding myself that I was beautiful.

But this confidence would be torn from me… dramatically by the end of my first day at my new school.

I felt like an outcast as soon as I stepped through the front doors of BMS. I didn’t resemble anyone else in the school.

When a girl in my grade approached me, I felt happiness roll over me for a moment, as it seemed that here was someone like me, but as soon as she spoke to me, I felt like an outcast once again.

“What kind of Chinese are you?” she asked.

I smiled and told her I was Vietnamese and Filipino.

I understood that she did not mean any harm, but still I was hurt, since her assumption emphasized our difference.

As the year progressed, the assumptions made by my peers got worse.

“Do you eat dogs?” I was asked.

“Ching Chong Ching Chong,” said one classmate.

“Are you smart because you’re Asian?” asked another.

“Chink,” I was called.

I was shocked that the people around me were openly using hateful Asian slurs. When I expressed my dismay at a racist remark, I was told it wasn’t racially motivated.

At an early age it was drilled into me that racism toward Asians didn’t exist; therefore, I was led to believe that it was not an issue.

In retrospect, it clearly was.

I tolerated jokes about my ethnicity because saying something would only give them more fuel.

“It’s a joke, get over it,” they would say.

Soon, whenever someone said the word “Asian,” my heart would drop in fear of what they would say next.

This was just the beginning of my encounters with racism.

After President Trump dubbed Covid-19 the “Chinese virus” last year, The Asian Pacific Policy and Planning Council announced that more than 673 cases of discrimination against Asian-Americans were reported in one week.

Even after seeing that statistic, I was still unsure if anti-Asian racism would be taken seriously. Is it necessary for the number to rise to 1,000 reports a week? 2,000? How many incidents must occur before the animosity becomes visible?

Since the Coronavirus pandemic began, there has been a new strain of anti-Asian racism festering.

This bigotry is more dangerous than the stereotypes we have become used to: Asians as powerful cyborgs, or as invisible.

When old strains of prejudice arise from the dark recesses of American history, they adjust to new circumstances. The recent rise reeks of late-nineteenth-century xenophobia.

Because of concerns that Chinese workers would take jobs from whites, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882. Asians were depicted as a “degraded” race whose influence would taint Americans’ values and were falsely associated with disease.

It is now the 21st century, and once again we are associated with disease. Racism never goes away; rather, it adapts to new conditions as old strains emerge from the depths of American history.

My daily racialized experience is more about anticipating hatred than being the object of it. Is it likely that I will be bullied because I am Asian? Is he going to turn me down because I’m Asian? Would they treat me differently because I’m Asian?

Bigotry can, however, happen when you least expect it. For example, While walking through my neighborhood, I saw an older gentleman smile at each of my next-door neighbors, who are Caucasian; but when I walked past, he put his mask up to his face and walked in the opposite direction. I wasn’t enraged — even before the pandemic my family faced bigotry–but now I was scared.

I was scared to be in a neighborhood where I was seen as the cause of a deadly pandemic. I was afraid to be Asian.

Since the COVID-19 outbreak, Asian hate crimes have been on the rise, mainly toward the elderly. Now I am fearful for my family members as well as for myself. These victims’ stories hit far too close to home.

Now we have to worry about acid being thrown on us on top of worries of contracting the infection, being laid off or losing loved ones.

Being Asian in America during the coronavirus outbreak is doubly isolating. You might believe that during a pandemic, everyone is alone. But ours is a different kind of isolation carved out by the insidious model-minority fallacy, which implies that racial inequities can be solved if you work hard and don’t ask for handouts.

Asian-Americans have always lived a conditional life in which we are guaranteed belonging if we work harder at being nice, hamming up acts of courtesy when we assist our neighbors, and internalizing any racial slights we experience.

The theory of the model minority is a fabrication that conceals systemic economic racism. Years of Western colonization, conflicts, and invasions have wreaked havoc on Asian-American families, causing intergenerational trauma.

During my freshman year of high school, I detested debating the model-minority myth because it felt like I was caught in a feedback loop. I was pulled back to refute the myth after denying it the first time. When the pandemic hit, I realized how profoundly the myth was embedded in the minds of both whites and people of color.

When I was a victim of a coronavirus-related racial incident, the attacker was not Caucasian.

How could it be that a person of color who has also experienced racial discrimation could turn their back and spew bigotry against an unfamiliar race? Isn’t that what others were doing to them?

“Chinese b***h!” shouted one of my peers.

I had to continue to walk as if nothing happened, and sadly, I wasn’t enraged by the words that were just said to me. I had to believe that it was not racially motivated and that it was only a joke.

If I saw it as racially-motivated and stood up for myself, I would only be judged more. I did, however, want to change my identity in that instance. I no longer wanted to be of Asian descent.

The hatred has gotten worse since Americans have been ordered to stay indoors. The Asian Pacific Policy and Planning Council received 1,843 reports of anti-Asian discrimination in an eight-week period last spring.

Working-class Asians who work in essential businesses, such as grocers, are at higher risk of contracting the virus and face anti-Asian harassment as a result of the shelter-in-place rules.

On April 5, a 39-year-old Asian woman in Brooklyn was severely burned while taking out the trash by an assailant who threw what is believed to be acid on her head, neck and back.

On March 16th, three Asian women were found dead from gunshot wounds at a spa. They then found another Asian woman dead of a gunshot at another spa a short distance away. Ultimately, eight people were found dead at three different spas, six of whom were Asian.

I’m furious. I’m terrified. We now have to worry about our own safety on top of fears of contracting the virus, being laid off, or losing loved ones?

It feels like many Americans don’t just think Asians have the coronavirus. They think we are the coronavirus.

As a journey to help end this discrimination, I have had inter-community and inter-racial conversations with anyone willing to listen. Having these conversations within the Asian community is important: Chinese Americans, Indian Americans, Vietnamese Americans and other AAPI people need to work together.

But we also need to broaden the conversation to speak with other marginalized groups including African Americans and Latino people.

We are all in this together, and that is the bottom line, And if we all feel the connective thread, that connective tissue, that’s what leads to longer-term, long-lasting welfare of us all.

Lana Lagman (she/her) began writing for the Beachcomber in the fall of 2020. She likes to cover stories concerning mental health, diversity and new medical/scientific...