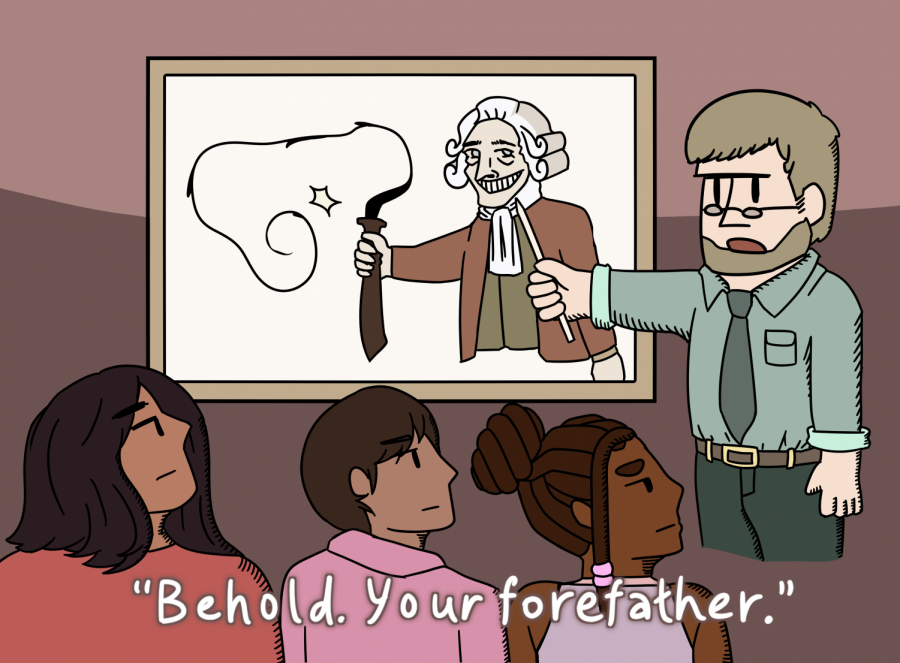

Our Eurocentric History Curriculum

“We focused more on the colonizers than the names of the people being colonized.”

On Sunday June 28, the Beachwood City Schools hosted the Rally for Educational Equity in the stadium. In line with the racial justice movement of summer 2020, catalyzed by the killings of Black Americans by police, Black student activists spoke extensively on a variety of topics, key among which was personal testimony relating to the hurdles faced by Black students at Beachwood.

This event delivered a powerful statement regarding the racial disparities in our school, and, in line with this effort to reexamine our school’s character and policies from a new perspective, we must reevaluate the content of our curriculum at Beachwood.

Speakers at the rally made repeated reference to Eurocentrism, but the idea of Eurocentrism is a concept that too frequently goes unexamined. For this reason, it is necessary to provide a nuanced explanation of what Eurocentrism is, present concrete evidence that it is a problem at Beachwood and explain what teachers and administrators can do moving forward.

The term Eurocentrism came to English from French, where it was first used by the French-Egyptian Marxian economist Samir Amin. Dr. Amin explains Eurocentrism as “an idealist construct … that opposes Occident and Orient in absolute and permanent terms”.

In his 1989 paper on the subject, this “idealist construct” is used to express “the irreducibility of historical trajectories” as part of a wider perception of historical development. To simplify, Eurocentrism operates on two assumptions.

The first is that “The West” (what Amin calls “the Occident”; a racial, geographic, and political group encompassing white Americans and western Europeans) follows an inherent pattern of development–westerners independently invent new philosophies, ideologies, and technologies which allows their society to develop and become more and more complex.

The second is that “the Orient” (what Americans would usually call “the Third World”, which, in this context, includes people of color in America) is comparatively static; the Orient does not progress, it is progressed by the West. Under this view of history, progress happens intrinsically for the West, and is then forced on everyone in the East.

People who have been taught with a Eurocentric lens will usually talk about the creation of the United States of America as an event spurred by an intellectual and spiritual connection to notions of “freedom” and “democracy”, and realized by Americans. This same perspective frames the appearance of the United States as a consequence of the European enlightenment, the colonization of North America, and the proliferation of protestantism in the New World. “The West” creates the United States, because it was the next step in its own development.

On the other side of the dichotomy, Eurocentrism argues that the American Civil Rights movement of the 1960s should be viewed as a time when African Americans, because they were exposed to the “uniquely Western” ideas of civil rights, demanded Civil Rights from oppressive actors within “the West”.

Notice that in this narrative, Black Americans are framed as passive actors; “the West” has provided African Americans with a constitution under which they are equal citizens, and so “the East” reacts to the hypocrisy of the United States government.This is the general pattern that is to be observed from the Eurocentric philosophy: Westerners act; minorities react. Notice also that from Amin’s perspective, notions like “the West” and “the East” are political. While the main distinctions in this dichotomy are racial, one can argue that white members of the LGBTQ+ community, or ethnic minorities within the West such as Jews and Romani are also victims of Eurocentrism.

Eurocentrism is particularly nefarious in education because it can be very subtly instilled in students without being explicitly taught.

“From a position of being a social studies educator, Eurocentrism means that the curricula that have been adopted are generally focused on European history, and give very little acknowledgement to Asian and African history,” social studies teacher Pam Ogilvy said.

If a person’s view of history is focused exclusively on the details of European and North American history, they will inevitably perceive the history of Asia, Africa and first nations as something that follows from the European history they know.

From here it falls upon members of our high school community, staff and students alike, to ask themselves if our social studies curricula disproportionately focus on the history of white Europeans?

We must also begin thinking critically about the choices that go into how we structure our curricula–take, for instance, the focus on Ancient Greece and the Roman Republic that we see in Western discussions of ancient history. We have a tendency to extol “the classics”, promoting their art, philosophy, and science as a precursor to our own. Do we do this because the Greco-Roman world is truly more relevant to discussions of ancient history than, for instance, the contemporaneous Persian empire, or because we, as westerners, prefer to see white people as the only group in history capable of innovation?

The Beachcomber conducted a series of interviews with BHS students, in which interviewees were invited to participate in an intellectual exercise of the format “name a … person who changed the world”. A “person who changed the world”, in this context would have to be a (deceased) historical figure, preferably one they had discussed in a social studies class.

From there, the eight students who participated were asked to name a white “person who changed the world”, a Black person, an East-Asian person, a South-Asian (Indian subcontinent) person, a Middle-Eastern person, a Latin-American person, and an indigineous (Amerindian, Pacific Islander, or Australian aboriginal), person.

Students were instantly able to name a white person, a Black person and a South-Asian person (with Martin Luther King and Gandhi being the most popular answers for the latter two), but every single interviewee struggled to name a person belonging to one of the other groups.

Ironically, when the exercise was repeated, this time using different kinds of Europeans (a Frenchman, a German, a Russian, an Englishman and an Italian), students could instantly name Napoleon, Hitler, Lenin, Locke and Columbus (among many others). These data cannot be used in any in-depth statistical analysis; the sample is neither randomly selected or large enough to make any statistically valid conclusions. However, students’ inability to name a single indeginous, East-Asian or Middle-Eastern person certainly seems telling of some Eurocentric bias in our education.

Other interesting perspectives revealed themselves in interviews with students.

“We focused more on the colonizers than the names of the people being colonized,” said one student when asked to name a historical figure of color.

Varying levels of exposure to the legacy of imperialism were displayed by student interviewees. One student, when asked why so many foreigners know how to speak English, said that it was because “people who speak English refuse to learn other languages”, and people of color learn English because “other places don’t have the god complex that we do”.

The reality that English was forced on so many nations through both violent conquest and economic subjugation, and that the prevalence of English in modern diplomacy is a remnant of generations of white supremacist colonialism, seems lost in the process of teaching.

Eurocentric education patterns are not exclusive to Beachwood, nor are they necessarily the fault of our social studies teachers. Teachers are required to meet (and more often than not, struggle against) rigid guidelines imposed on the state level. The official Ohio Department of Education “Social Studies Standards”, for instance, outside of a vague reference to “the displacement of American Indians” as a consequence of western expansion, fails to mention how the United States purposefully decimated the population of the Great Plains Native Americans in a genocidal program of forced relocation and extrajudicial execution after the Civil War. These “Indian Wars”, alongside the atrocities committed by the Belgians in the “Congo Free State” and the Boer Wars of the British Empire, are today seen as the great forgotten genocides of the 19th century–and our curriculum continues the shameful tradition of obscuring them.

“State tests dictate that you have certain things covered–because there isn’t room for the second perspective on the test,” middle school social studies teacher Garth Holman said.

A tentative solution Holman uses in his class is to supplement the required Eurocentric state narrative with information that exposes students to new perspectives. For instance, while the state requires Holman only to teach students about the Gutenberg press, Holman takes the time to expose students to information about contemporaneous wood-printing techniques that were being developed in China around (and, in fact, before) Gutenberg’s times.

“The district is pushing history teachers to take the time to do that–to make that part of the whole story,” he said. “[The responsibility falls upon] the individual teacher, with the encouragement of the district.”

The inclusion of elective classes in the curricula, such as Kathryn Barney’s African-American history class or Pam Ogilvy’s human rights and conflicts class (which is, in essence, a semester-long investigation of genocides committed in the last century) also broaden the narrative that students are presented with. In the English department, an African American literature class is offered by Casey Matthews, with a similar effect.

The teaching of history is inherently political, and the politics of Eurocentrism in education are a substantial hurdle for educators and administrators. The current presidential incumbent, for instance, proudly promises to “teach American exceptionalism” if he is reelected as the only bullet point describing his agenda for the education system. Some white Beachwood parents take to Facebook to argue that the presence of literature written by Black authors in the curricula is an attempt by the school to further a nefarious left-wing agenda.

However, the discussion surrounding Eurocentrism is not a matter of opinion.

“History is the story of people–not of the elite–history is your story and my story. It’s what makes us who we are,” Holman said.

A potential solution to presenting a holistic view of the world while avoiding the proverbial political thicket may be to use primary sources. Holman, for instance, has students read Columbus’s diary as part of their discussion of trans-Atlantic contact.

“I could conquer the whole of them with fifty men, and govern them as I pleased,” boasts the celebrated explorer in one passage.

Because primary sources are inherently free of commentary, they can be used to provide an accurate narrative of history without risking accusations of political brainwashing.

“I took African American literature, and that was the first time I encountered many of the works written by Black Americans,” one student said during their interview, “And, I’m afraid I wouldn’t have gotten to read those anywhere else.” Primary sources can offer curricula insurmountable value, while also encouraging students to develop their own conclusions.

And, so long as a diverse body of sources is used, the conclusions students arrive at will be non-Eurocentric. Eurocentrism is not explicitly written into history. It is taught in subtle ways, from the way textbooks arrange their chapters, to the things we see on the news. Our school, like our state and our country, has a ways to go with respect to our social studies curriculum, but there is pride to be found in our collective effort to combat Eurocentrism.

Alice Soprunova (she/her) began writing for the Beachcomber in 2019. She covers stories pertaining to issues of social justice inside and outside BHS....

Yang began illustrating for the Beachcomber in the fall of 2019. In addition to this, he participates in the school's Academic Challenge and Science Olympiad...

![“My parents have always said that education is important. My parents are Chinese immigrants, I'm Chinese American, [and that's a] value that has always been ingrained in our community,” said Senior Lyndia Zheng, pictured with Tony Zheng](https://bcomber.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/DSC_4244-600x400.jpg)