Coming Together: When Kids Become Victims of Mass Violence

School shootings and racial violence.

The acidic anxiety that trails behind these two invisible, bitter subjects is hiding between the concrete walls of my American high school.

Since the Columbine massacre in 1999, the quantity of mass shootings in the United States has continued to rise year after year in American schools.

In early November, an estimated 50% of BHS students responded to an unscientific Beachcomber survey indicating that they do not feel safe at school due to the national threat of gun violence. But there was another factor playing into the results of this survey: race.

Racial disparities have become a particular focus of our national discussion beginning in 2012, with the death of teenager Trayvon Martin, a junior at Dr. Michael M. Krop High School in Dade County Florida.

Following Martin’s murder and the acquittal of his shooter, a spiral of killings perpetrated by white legal authorities against African Americans such as the cases of Michael Brown and Tamir Rice have gained national attention.

In light of this national discourse, racial polarization and feelings of physical insecurity have increased here at BHS as well.

On Wednesday, Feb. 14th, 2018, around 3:00 p.m., I walked home from school to see the television on in the background, another breaking news segment running slowly across the screen– but this time, there were kids walking out of a school with their hands behind their heads.

It was the live footage of the Stoneman Douglas High School Shooting in Parkland, Florida. It was a type of imagery that that I, and many of my peers, had seen far too often.

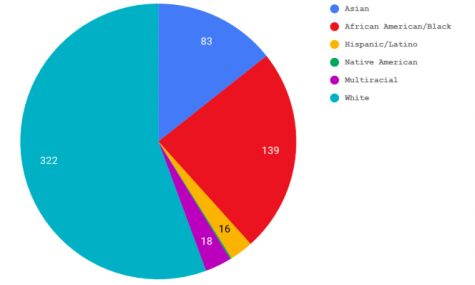

We are all products of the environment that surrounds us. For minority students, such as the 139 African-Americans who attend BHS, it is hard to escape a sense of fear both in and out of school. Far too often I see headlines documenting violence perpetrated against minorities due to the color of their skin, religion or ethnicity.

Nearly every BHS student has, since elementary school, developed a sensitive reaction to every school shooting– after all, the Chardon shooting took place the day after I turned nine years old. Not too far from home, either. Then came Sandy Hook, Freeman, Marshall County, Parkland and Santa Fe.

I’m now 15. For time’s sake, I’ve chosen to leave out about forty other high school shootings since 2012. A comprehensive analysis of school shootings can be found here.

Statistics prove that African Americans have become victims of racially-motivated violence more than any other demographic group in the United States. This data includes mass shootings.

In 2015, a white male shooter committed an incomprehensible massacre in a predominantly African-American church in South Carolina, killing nine black civilians.

“I would like to make it crystal clear, I do not regret what I did,” the perpetrator later wrote.

Just over one month ago, another white male shooter walked into a Jewish synagogue in Pittsburgh and opened fire on members of the congregation, taking at least 11 lives.

It’s not just the schools that have become targets of mass shootings– it’s the places of worship and the people, too.

I recently collaborated with other students in hosting an open forum to discuss the rise of violence motivated by racial and religious differences. Needless to say, the room filled with raw emotion.

The disheartening realization that many attendees came to by the end of the forum was stated clearly by junior Tiani Allen.

“None of the students in this building are sheltered from being the perpetrator, nor are we guaranteed shelter of becoming a victim,” she said.

In other words, the reality of today creates an immense uncertainty. We don’t know what psychological factors influence people to commit these acts of violence, and we don’t know who might get their hands on a gun. There is a a clear, blatant, underlying fear in practically half of the student body, that there is no denial of a possibility that we won’t walk out of school alive.

The overwhelming feelings expressed by students went far beyond Allen’s statement, leading to a tense conversation about the environment within our own school.

Senior Dani Smith, a member of the Minority Achievement Committee Scholars, expressed her frustration about feeling both emotionally insecure and physically unsafe at school.

“Some of us feel like we have to talk a certain way or act a certain way to be accepted, but when other races talk like ‘us,’ they aren’t looked down on,” Smith said.

“It’s the emotional part of it, and then all of us together fear losing our lives to someone … who shouldn’t have a gun in the first place,” she added.

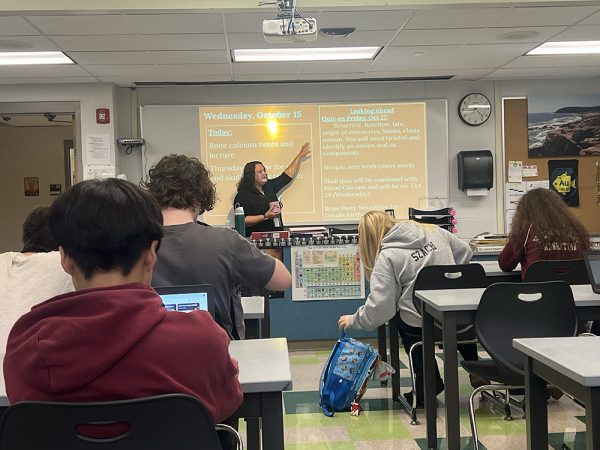

“I think it’s clear that kids who come to school are more fearful to show up,” her classmate Jayson Woodrich added. “…And sometimes it causes problems and anxieties about feeling more safe in school [that make it harder to] actually learn something.”

From every voice in the room, two conclusions were clear: the ever-present fear of losing our lives to a bullet, and the idea that race relations in our school must change.

Senior Dasianaé Byrd elaborated in one of the closing comments of the forum.

“Our school is diverse, there’s no question,” she said. “But the inclusion of other races together feels like it doesn’t exist.”

Her classmate Antoine Whitsett, added, “The kids have to communicate.”

For a second, I asked myself why Dasianaé may have said that, but in reality, I knew. Through the past two years at BHS, racial tensions have risen through insensitive comments having not been thoroughly addressed by students and administrators, and those same remarks have haunted minorities with constant, underlying feelings of oppression.

Taking into account everything said at the forum, I tasked myself with understanding how we move on, and how to bolster race relations in my school. I like to think of race relations, at its most basic level, as a friendship, in that we understand how to connect with each other despite our differences.

Take, for example, my relationship with my best friend Emily. She swims, I do track. She’s good at physics, I’m good at history. She is more often able to see the bright side in things, I’m not. She’s Chinese-American, and I’m African American. How are we best friends?

I have no answer other than that our differences level out as we connect from our similar upbringings. What we have in common is what holds us together, our similar pasts and our family’s histories.

Not much differs in finding a common ground for race relations in the student body. Much of the escalated tensions in BHS have developed between Jewish-American students and African-American students.

A prerequisite to pushing race relations forward is that we have to collectively understand the demographics of our educational environment. The following table represents the races of the student body at BHS, with statistics provided by the guidance office.

Because the majority of our school is predominantly white and Jewish, and the second largest group is students of African descent, the rise in xenophobic hatred in the United States impacts us all.

There is no doubt that the current political powers of the United States have caused an increase in students’ fear. Lack of gun control, racial prejudice and police brutality have created a toxic emotional brew.

When elected officials rush to scapegoat minorities, or to scapegoat anyone for that matter, authorities fail to address the real causes of our problems and instead normalize acts of hatred towards minorities.

Senior Orly Einhorn spoke at the forum about the Pittsburgh shooting.

“I shouldn’t be afraid to be a part of a faith,” she said. “I shouldn’t be afraid to go to shul.”

African American kids shouldn’t have to be afraid to go out in the streets feeling like police forces are more likely to shoot them than save them; they shouldn’t have to think twice about whether or not micro-aggressions are the only compliments they’ll ever receive. African American students shouldn’t feel the lingering effects of 300 years of slavery penalizing them in society, but they do.

Jewish students shouldn’t feel like their own places of worship are now endangered due to a legislative standstill in addressing a nationwide security crisis. Jewish students shouldn’t feel the lasting prejudice over centuries of anti-Semitism that came to fruition with the Holocaust, but they do.

Every student has the right to feel safe in the learning environment, surrounded by their own unique histories. We’re not all that different, it’s just that, well, sometimes acknowledging our differences and the incidents that have caused races to regress is the only way we can progress, together.

Our fears may shake our skin down to the bone, but the color of that same skin is not a reason to avoid coming to terms with our pasts, in order to make our school a place where every heritage, and every one is valued. Race relations in our school have to change, and it starts with students finding common ground.

If we truly care about moving forward and listening to all voices like we say we do, then the first bullet in taking action may just stop lethal bullets from penetrating our bodies.

The rise of mass shootings across the country is terrorism, and if we’re all going to fight it, for the purpose of seeing another day, then we must do it together. It is no longer time to “talk” about it, and it’s no longer time to pretend like the assault rifles that can kill us and the color of our skin does not play a role in our perception of reality inside and outside of school.

Sometimes, just sometimes, we have to put aside our differences for the greater good of each other.

Elizabeth Metz began writing for the Beachcomber in 2018. She enjoys covering identity politics and sports. In addition to writing for the Beachcomber,...