PARCC Exams Will Fail to Improve Our Educational System

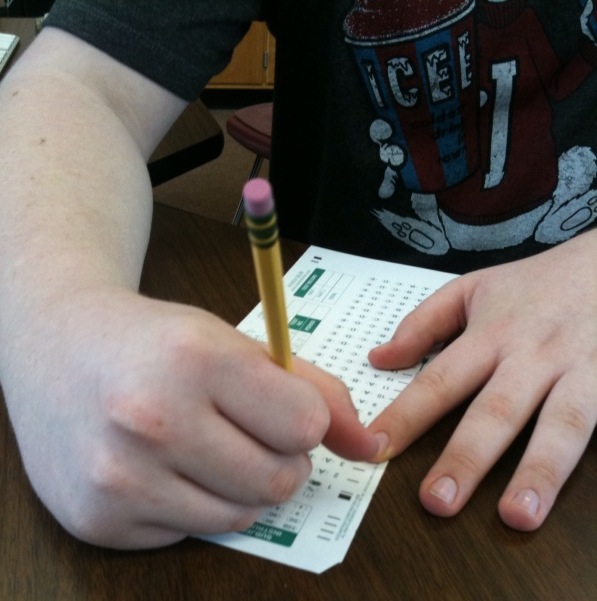

This year, the first class of BHS students will take the Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers (PARCC) exams, which were designed to align with national Common Core State Standards, replacing the Ohio Graduation Tests.

The Common Core’s lofty goals will undoubtedly raise expectations for students and staff. However, with their rushed implementations and high stakes nature, the PARCC exams will ultimately fail on their promises.

There is no doubt that Common Core standard is a well-intentioned policy. A a college education has become essential for financial security. Yet upon graduating high school, American students do not seem to possess the skills necessary to succeed in college and beyond.

A 2013 report released by the ACT revealed that only 26% of high school graduates who took the test were deemed college-ready in the four subject areas the exam covers. According to the Ohio Department of Education, 40% of college students enrolled in Ohio’s public universities or community colleges required remedial classes. These students had graduated high school, yet were still not ready for college work.

Stuck in high school level classes months after graduation, these students are more likely to run out of the time, money and willpower to obtain their degree. The reformers behind the Common Core should be commended for trying to bridge this gap by imposing more rigorous standards at the primary and secondary school levels.

However, due to rushed and poorly-executed implementation, students are unlikely to see the benefits of the new standards. Several BHS teachers have commented that the new exams are unreasonably difficult. A large factor here is that students who have been trained to think one way are now being forced to make a 180-degree rotation in their thinking near the completion of their high school careers. When students are forced to adjust to a new curriculum, their education becomes disjointed, and the most vulnerable students are more likely to fall through the cracks.

In an article published in The Atlantic, Jason Cornett, a teacher from a low performing school in Kentucky, noted that, “[Students] are still having trouble mastering the basics and you’re trying to add stuff on top. Over all [Common Core] is a positive change, but it’s been hard on some of the kids in the middle of the transition.” Similarly, a New York Times article published this past summer chronicled how a star student’s confidence was damaged along with his zeal for school after Common Core standards were introduced to his third grade class. One Beachcomber editor recalled how when the Beachwood City Schools switched math curriculums in her fifth grade year, there were gaps in her education, causing her to be taught long division by her parents. If educators want to increase the rigor in children’s education, they need to take a more gradual approach. A disjointed curriculum only produces children with disjointed knowledge.

As students struggle to learn in radically new ways, they will be impeded by the anxiety of end-of-course exams. Standardized tests are inherently stressful, but at least with the majority of them, only the test-taker’s future is at stake. However with the PARCC exams the students’ diplomas, their teachers’ salaries and their community’s property values are all on the line. This places unnecessary stress on already overburdened teens. With this kind of high-stakes testing, teachers become so preoccupied with teaching to the test that they are likely to instruct their students to use scripts and rote-memory, exactly the opposite of what the Common Core was designed to encourage.

If policy makers are going to impose standards, they need some means of evaluation, and standardized testing presents a logical mechanism. However, the PARCC exams should simply assess how well each school meets the standards. If a school does not pass certain benchmarks, the state should work with the school to improve. There does not need to be a system of penalty and rewards. Schools are not businesses; the hierarchy of incentives that the Common Core establishes is unnecessary and counterproductive in an educational system where the goal is an educated populace, not profits.

When BHS students undergo preparation next year for the rigorous PARCC, don’t expect an overnight miracle in students’ higher-order thinking abilities. Instead, recognize it as another well-intentioned policy that will ultimately fail to deliver.