Can School-Based Prevention Programs Change Student Behavior?

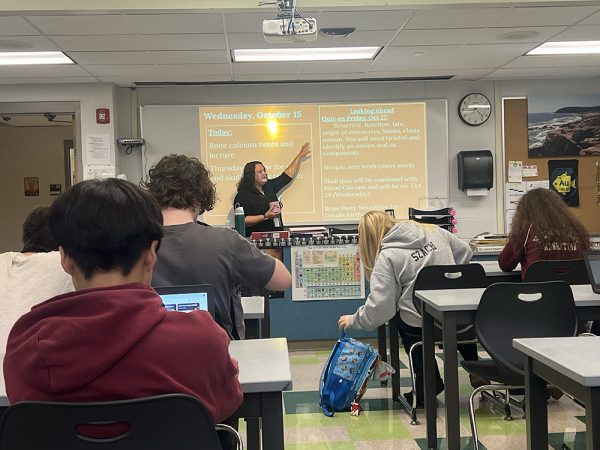

In sixth grade, as part of a series of anti-drug programs, a school nurse told my classmates and me that we should stand in front of a mirror and practice saying no. This only happened once, but it was so unprecedentedly ridiculous that I remember it clearly five years later.

While I personally don’t have any difficulties pronouncing one-syllable words such as “no” (I can even articulate two-and three-syllable words without a problem), perhaps I had classmates who did struggle with one whole entire syllable.

Anti-drug, anti-alcohol and bullying prevention programs have yielded perhaps some of the worst results of any well-intentioned program ever conceived, next to Prohibition, which ended up significantly increasing the crime rate. Studies conducted as early as the 1990s have shown that such programs at schools have either no effect or a negative effect on students’ decisions to do drugs, drink, bully and become increasingly annoyed at the administration.

University of Texas at Arlington criminologist Seokjin Jeong found that anti-bullying programs have a negative effect because they teach students new techniques including how to bully without leaving evidence. These programs have also changed the definition of the word “bullying.” A generation ago, bullying described extreme forms of physical or verbal abuse. Now, if you believe these programs’ claims, bullying includes failing to go out of your way to be extremely nice to every single person. Many schools, especially elementary and middle schools, have blurred the lines between playfully teasing and bullying, causing students to discredit anti-bullying programs at best, and mock them at worst, as many students frequently do.

The phrase “you’re being a bully!” is frequently thrown around at my lunch table, generally in the context of people stealing food from one another. By “stealing,” I mean one person taking two pretzels from their best friend who has a whole bag. Although I highly doubt anyone thinks twice about accusing friends of bullying, this happens because programs have defined bullying to include insignificant acts such as these. When small acts that could maybe be considered slightly annoying if you’re already in a bad mood are considered bullying, actual bullying is taken far less seriously. In this respect, anti-bullying programs have actually made it harder for real victims to get help.

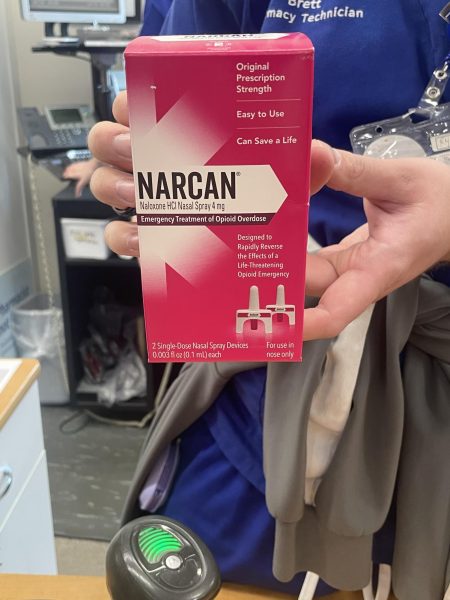

Anti-drug and alcohol programs have an even worse impact. According to the National Drug Strategy Network (nsdn.org), “Youth believe the information they receive is inaccurate and misleading because the programs equate substance use with abuse and do not reflect the students’ actual observations and experiences.” When students think the information they receive from these programs is inaccurate, they want to do exactly what they are told not to.

According to the organization’s web site, “Most programs incorporate some form of a ‘scare-tactic,’ which may be disguised as ‘decision making’ or “’providing facts,’” because the drug policy deals only with serious punishments, rather than actually helping the students.

Simply put, students are basically told they have a “decision” between a) staying away from drugs, alcohol, anybody who does those things, has thought about doing those things, or even knows somebody who has thought about doing those things, or b) being expelled and possibly put in juvie, simply for being in the vicinity of somebody thinking about taking one more Ibuprofen tablet than directed.

These ‘scare-tactics’ also imply that there is no hope for people already using, and may even attempt to ostracize those people. This is truly ironic because many of these schools also harp against bullying, and consider exclusion a form of bullying.

I’ve learned quite a number of life lessons from school, and even an academic thing or two that showed up on the ACT. However, that seems to be where the lessons stop and the belaboring begins, because anti-drug, alcohol and bullying programs tend to do more harm than good.

Anti-substance programs might have more of a positive impact if instead of saying “smoking is bad,” which could actually encourage students to try it out of curiosity, they simply stated the facts, such as “smoking tobacco causes tar build-up in your lungs.” That way, if the second-grade teachers’ science lessons were effective, students will come to the conclusion on their own that smoking is not such a great idea because tar generally does not belong in your lungs. If the adults who run these programs simply cannot bear to let students draw their own conclusions, any information provided would be significantly more credible if it came first-hand from someone who had overcome alcoholism or drug abuse.

Therefore, instead of attempting to ostracize students who are addicted to drugs or alcohol, schools should offer those students help. Additionally, these students should have the opportunity to share their stories with others in order to prevent more people from going down the wrong path.