A Case Study in Bad Television

The Creators of “Big Mouth” Bite Off More Than They Can Chew

Andrew Glouberman meets the hormone monster.

Big Mouth is a Netflix adult animated sitcom created by Nick Kroll, with a cast populated by famous character actors, stand-up comedians and Hollywood insiders like John Mulaney, Jason Mantzoukas, Jenny Slate and Jordan Peele.

The show centers around a group of middle school students at the cusp of puberty, with episodes centering around masturbation, menstruation and first crushes — as well as some more adult issues like depression, anxiety, homophobia, racial identity and sexual assault.

Despite its talented cast and good intentions, Big Mouth isn’t too interesting on its own merits, but is fascinating as a case study in bad television.

As it is, Big Mouth is a bad show, but with just one minor tweak here or there, it could easily be a mediocre show — something worthy of its existence in the television market — not some masterpiece, but a program with a sort of cohesive gestalt to it, comparable to such mediocre programs as, for instance, the last few seasons of The Simpsons.

The creators of Big Mouth, whether out of a vain sense of individuality or out of genuine incompetence, seem to do everything in their power to stop their show from being something greater than the sum of its parts.

Big Mouth has (some) elements that work. It has (some) well-written characters, (some) funny jokes, (some) well-structured episodes and (some) genuinely heartfelt moments of enticing drama. Big Mouth has its gems, but it also has its trademark turds.

The main fault of the show may honestly be simply that series crater Nick Kroll, unsatisfied with simply voicing the primary protagonist and his “hormone monster” (one of the various fantastical elements of the show used to punctuate its thematic trajectory), insists on imparting his voice onto every other recurring character on the show.

Unfortunately, they all sound the same, and Kroll seems to see a “funny voice” as both set-up and punchline, resulting in an auditory experience that is both painful and embarrassingly unfunny.

The show is a combination of three narrative worlds. One is the primary world of middle schoolers going about their classes, familial struggles and awkward firsts. The second is a sort of nightmarish hellscape of talking genitals, scatological humor and elements of crass shock comedy so intentionally vile (like the aforementioned Kroll impressions) as to masquerade as comedy.

Finally, we have an Inside Out-style world of metaphor, in which the emotions and mental health issues of characters are personified in corporeal surrogates such as a purple “depression kitty” and an annoying “anxiety mosquito.”

A copious amount of narrative capital is given to connective tissue — elements introduced to bridge these three worlds. In another failing of the show, these elements of “connective tissue” end up taking up so much time and space (as is necessary given the ridiculousness of the respective worlds) that they become central fixtures in and of themselves.

The aforementioned “hormone monster,” who visits the children and acts as an avatar of their puberty, seeks to bridge the middle school world with the bizarre scatological shock-humor (rather than simply having a character’s vagina talk, the talking is framed as a conversation between the character, their hormone monster and the talking vagina).

The world of metaphor is joined to the world of potty humor by a device in which metaphors for mental health issues speak directly to the hormone monsters (see the rivalry between Jessi’s hormone monstress Connie and the depression kitty).

Finally, the human world is bridged with the metaphorical world through the introduction of various fantastical elements grafted directly onto the human world. This is why the ghost of Duke Ellington lives in the attic of the protagonist, and why all the characters inexplicably gain super powers for the season three finale.

These three worlds are, in turn, braided together through a metatextual series of fourth wall breaks and parodies of pop culture.

Woof.

The project is not without ambition, but that ambition seems to be wildly disproportionate to both the creative resources of the showrunners and the space dictated by the genre. It seems that the writers didn’t just bite off more than they could chew, they continued to bite off more and more and more without having chewed anything they had already bitten off.

Sitcoms traditionally have simplistic premises, and the complexity comes through character interactions and wacky hijinks. Big Mouth instead pitches a world so complex and byzantine that it seems downright inappropriate against the backdrop of pee-pee and poo-poo that the show loves so much.

Remove any one element, and something palatable appears. Remove the inspid fourth-wall breaks and constant references to pop-culture and you have a complicated science-fiction show that can be a bit hard to follow, but is, at the very least, commendable in how seriously it takes its bizarre premise.

Remove the gross potty humor and talking penises and you have a somewhat cliche story about middle schoolers whose anxiety, depression and other feelings are personified through talking animals.

Remove those talking animals but leave in the scatological humor and the hormone monsters, and you have a gross-out comedy about puberty, complete with shocking incest jokes and talking feces.

At the very least, remove some of those horrendous Nick Kroll voices (preferably the character of Coach Steve), and it becomes a version of Big Mouth that is pleasing to the ear. Any one of these changes would result in a premise that works. The producers of Big Mouth, however, seem to have resolved to keep the show subpar.

Big Mouth doesn’t show any restraint, both because restraint is anathema to its toilet humor, and because the showrunners seem to believe that randomness in and of itself is humorous. Random elements thrown into a television show can be hilarious, if they gel with the tone of the program and feel at home in the narrative.

Pulling off comedic randomness takes a deft ear and a great deal of narrative finesse — which is why Bojack Horseman’s Princess Caroline being reduced to “A Tangled Fog of Pulsating Yearning in the Shape of a Woman” by an unreliable narrator is funny, but David Thewlis voicing a “Shame Wizard” on Big Mouth who serves as a surrogate for the characters’ pubescent senses of shame is not.

The show also suffers from another existential contradiction — it presumes to satirize the mainstream, but, by virtue of budget and content, is inseparable from the mainstream. When the characters attempt to ridicule 13 Reasons Why by sarcastically noting that teenage depression “makes for good television”, the satire proves hypocritical because Big Mouth is also a large-billing Netflix project, profiting off if not actively seeking the viewership of children, and using important mental health and political topics to aggregate viewership.

Big Mouth attempts a snide joke about TV show host John Oliver, only for Oliver to appear as the main characters’ camp counselor a couple seasons later. The show also, on several occasions, features a parody of Firefly actor Nathan Fillion — and, because the showrunners have the necessary resources, they go ahead and cast Nathan Fillion himself in the role.

While writing this analysis, I told one of my friends that, while researching, I was shocked to discover that none other than Kristen Bell stars in the role of “Jessi’s vagina”. Upon fact-checking, however, I realized that Kristen Wiig voiced Jessi’s vagina.

Had I simply swapped one Kristen for another? No. Kristen Bell voices Pam, a sentient pillow who one of the main characters uses to masturbate and then unintentionally impregnates, spawning a human-pillow hybrid.

The show featured both Kristens, and playing roles so similar in tone that it became a coin flip as to which was which. The more you watch the show, the more recognizable Hollywood voices you catch, and the less genuine the tone becomes.

In December of 2020, Netflix released Season 4 of Big Mouth, causing a minor media splash for a variety of reasons. First of all, Big Mouth would be introducing a trans character into its cast in the form of Natalie, voiced by former Disney star and trans woman Josie Totah. Secondly, Jenny Slate, the white voice actress who previously played Missy (a biracial character) would be stepping down.

At first blush, the transgender representation on Big Mouth deserves praise, as it is uncharacteristically competent. With a show of Big Mouth’s reputation, what with the talking genitals and episodes centering around ejaculating, you would expect an attempt at trans representation to end up dirty, crude and offensive.

In an odd twist, Big Mouth presents a compassionate account of a trans girl returning to her childhood summer camp — anxious about meeting people who have known her as a boy her entire life, alienated by activities she can no longer comfortably take part in (like swimming), and angry at her cisgender bunkmates who see her as a vehicle for their own wokeness. Natalie doesn’t feel like a trans person written by a cis person; her anxieties and coming-out story seem consistent with most trans women’s experiences.

Upon further analysis, however, the trans representation on Big Mouth stops being really all too commendable. It is objectively good representation, but it is so good that it seems inappropriate in an otherwise bad show — and therefore fails to be good representation within the framework the previous three seasons have set up.

Take for instance Season 4 Episode 3, “Poop Madness” (yes, that’s how they title their episodes). This episode is given such a delightful name because Andrew (John Mulaney), the secondary protagonist, has not defecated all month while he has been at summer camp, and now, on the last day of camp, he has entered a state of “Poop Madness,” what with his feces building up in his body and backing up all the way to his brain.

In the same episode, Natalie notices that Seth (voiced by Seth Rogen) has a crush on her and, after seeking advice from her friend Jessi, follows him into the forest to look at a dead bird he found (which she knows is just a pretense for him to kiss her).

Natalie has her first kiss with Seth, but afterwards he lets slip that he is uncomfortable walking back to camp with her, as he doesn’t want his friends knowing that he kissed a trans girl. This is the sort of thing that trans women have to deal with on a regular basis, and it is refreshing to see this (somewhat cliché) scenario playing out in a massive Netflix project.

While Natalie is having her first kiss in the forest, however, Andrew is writhing in agony on the ground as a clump of feces with a face (voiced by, of all people, Paul Giamatti) sticks out of his rectum and yells at him to not release his bowels.

When Nick (Nick Kroll), Andrew’s estranged best friend, finds him in this compromising position, they make up, and then Andrew defecates in a way that is meant to evoke childbirth — with Nick then swaddling Andrew’s feces like a newborn child and bringing it with him on the bus home.

All this is to say, there is a fundamental distinction between how Big Mouth portrays cis characters and trans characters. Big Mouth is obsessed with feces, urine, ejaculate and menstrual blood — but this motif is not extended to its transgender characters, because the showrunners are afraid of the risk involved with depicting the bodies of trans people.

This can be read as no more than woke overcompensation — the sort of “trans people are braver than the marines” liberal goulash that comes from cisgender people going out of their way to assert their allyship.

But it can also work to perpetuate even more harmful stereotypes about trans people. By grafting this comparatively tame story about a trans girl onto Big Mouth, the showrunners, whether intentionally or not, invoke analogy between its plotlines. Because shows (unless they’re Big Mouth) have a consistent tone, we are led to assume that we are meant to react to the different main characters in similar ways.

So what then, are we to take from this odd juxtaposition? That kissing a trans girl is just as disgusting as defecating a massive talking stool in the woods? In a show that praises itself for the “risks” it takes, the inherent risk of trans representation seems to be understood in the same way as the “risk” of alienating your audience through an obsession with poop and pee.

The entertainment industry desperately needs stories like Natalie’s — just not in the same breath as “Poop Madness”.

Big Mouth’s racial dimension is more successful in its fourth season than its foray into trans issues. Ayo Edebiri takes over for Jenny Slate midway when Missy Foreman-Douglas, a half Ashkenazi Jewish, half African-American middle schooler has an epiphany regarding her mixed heritage.

However, the (very much necessary) cast-switch can also be read as a reassertion of the age-old canard that biracial people in the United States have an active choice to be either essentially white or essentially black — with a biracial character being first voiced by a white woman, and then by a black woman after she comes to terms with her identity, the implication could be interpreted as an endorsement of a binary model of race that is fundamentally toxic for biracial people.

Many moments in the program merit praise: For instance, one unique and realistic plot point is when Matthew learns that being “young, gay and mean” is not a personality trait, and that the catty self-defense mechanism he has developed will inevitably undermine his future friendships. The character of Jay Bilzerian (voiced by the amazing Jason Mantzoukas of Parks and Recreation, The Good Place and Brooklyne Nine-Nine fame) is frankly hilarious and may be the most entertaining part of the show.

Even some elements of Big Mouth’s crudeness deserve praise — there is something very refreshing about how Big Mouth pulls no punches in its frank and honest discussion of women’s health issues. And the episode “The Head Push” alone can pass for recommended viewing because of its elegant statements on consent, slut-shaming and coercion.

However, the snippets of above-average LGBTQIA+ content, the occasional relatable character moment, and the once-in-a-blue-moon laughs do not redeem Big Mouth because, at its heart, its refusal to accept the notion of restraint — comical, visceral or narrative — stops it from having any cohesive sense of identity or purpose. Big Mouth tries to be South Park, Stranger Things, Bojack Horseman, Inside Out, Community and Dear White People all at the same time. And it fails at being every single one.

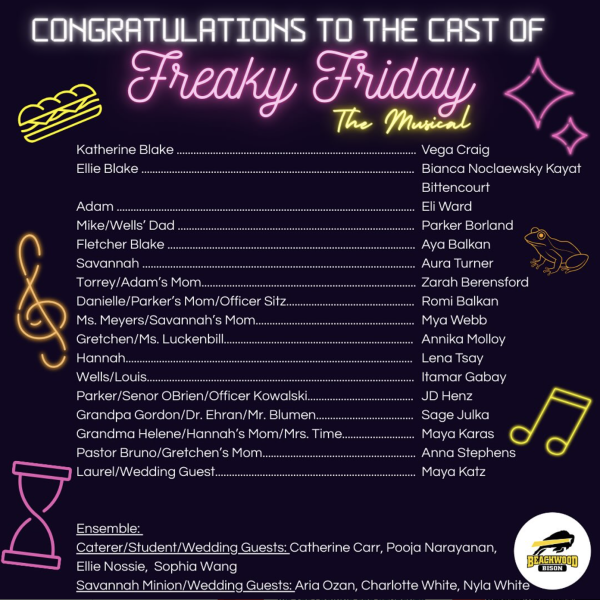

Alice Soprunova (she/her) began writing for the Beachcomber in 2019. She covers stories pertaining to issues of social justice inside and outside BHS....

Robert Simpson • Jun 30, 2021 at 10:15 AM

awwww i think someone is grumpy that they’ve never created anything, and think they’re intelligently breaking down something that brings some laughter into the world, while also taking on real, and serious issues