A Marxist Reading of TikTok

A spectre is haunting the Internet–the spectre of TikTok

In 2016, Beijing ByteDance Technology Co Ltd. released musical.ly, a lip sync video-sharing platform today most remembered for giving the world Jacob Sartorius and other faux riche preteen garbage celebrities.

In 2018, however, a triumph of rebranding transformed the app into a central pillar of modern meme culture, a quasi-legal dating app for minors and an online marketplace of fleeting clout.

This new colossus, which will almost certainly define adolescence for a vast cohort of gen-z North Americans, is nothing more than the streamlining of centuries-old Western practice of art as an exercise in attaining and communicating power.

Part 1: I’m already tracer

Any analysis of TikTok must begin with an assessment of that which draws the majority of its clientele: memes. It is not the purpose of this article to either define or analyze what a meme is, countless works (most of them regrettably written by the Alt-Right and intellectual dark web) have assessed the power of memes to disseminate and popularize messaging. However, the meme itself, for the purpose of our analysis of TikTok, serves the same function as, say, the advent of the novel in the 18th century in an analysis of the French Revolution.

The Marxist theory of art places all art, including its enjoyment, into a dialectic materialist context. Aesthetics, or the enjoyment of art for its own sake, is contingent on realities of class, gender, race and sexual identity. Your enjoyment of a work of art, be it a meme or an expensive Rothko (which is a meme in and of itself), is no more than a reflection of your status within a material world.

Thus the assertion that anyone is only “in it for the memes” falls apart under any level of Marxist scrutiny. A meme can only serve as a unit of content encapsulated, not as actual content. It is a fallacy of the internet that memes are as versatile and universal in utility as C6H12O6. In truth, the kind of meme you enjoy has almost everything to do with socioeconomic status, like any work of art.

The “I’m already tracer” meme, an infamous staple of TikTok in its infancy, exists in a wider context of the post-GamerGate discussion of female and LGBTQIA+ representation in video games like Overwatch and the public image of the gaming community.

Part 2: Stupid boy think that I need him

There comes a time when every person who has downloaded TikTok realizes that the enjoyment they take in the app is not ironic, perhaps was never ironic. They are not mocking the TikTok community, they are the TikTok community.

This, to me, at least, is analogous to Marxian class consciousness. And why not? TikTok has a veritable class structure. The TikTok dream is, after all, the American dream: to become “TikTok famous”, a member of the TikTok bourgeoisie, to accumulate clout—a facsimile for socioeconomic power on the platform—via likes. The acquisition of clout via the currency of likes is identical to the acquisition of capital under capitalism via the currency of, well, currency.

In a recent ContraPoints video titled “Opulence”, Natalie Wynn alleges that American Hip-Hop culture is an unironic celebration of the conservative American dream, with artists celebrating their rags-to-riches story while displaying their wealth in a positive feedback loop of commodity fetishism. This exemplifies the TikTok cultural trajectory.

Everything done on TikTok is done in the interest of clout-capital. Any activity, from jumping on trends, to making cheap jokes, to sexualizing oneself is instantly justified by its utility. That which generates revenue is inherently good under the TikTok capitalist system.

Many mock TikTok as an unofficial dating app for teenagers, with minors asking people to “hit them up” in their videos. While this assertion is accurate in a very cosmetic way, it is pretty irrelevant to our reading, as the acquisition of a “TikTok boyfriend” with curly brown hair and blue eyes is just another part of the TikTok clout game. Sex, or the sex symbolized by the subculture of girls deriscively called “TikTok thots” is no more than a litmus test of power.

A recent trend on the platform have been videos such as these, with girls lip-syncing to ‘STUPID’ by Ashnikko (a song that is popular on TikTok and nowhere else). While the audio clip is flirtatious, this phenomenon evidently has more to do with a demonstration of power than anything else.

Part 3: Martha Dumptruck in the flesh

TikTok as an institution is more than a platform that accepts and transmits meaning. Certain trends and concepts would not today exist without the platform. TikTok is thus not just a passive actor in the wider cultural discourse.

This way in which the medium of art can work to simplify and sanitize the art it produces has been discussed by the Marxist critic Theodor Adorno in his description of the “Culture Industry”, the mechanism that sells politically “safe” units of art through Hollywood and other bourgeois institutions.

“For the present the technology of the culture industry confines itself to standardization and mass production and sacrifices what once distinguished the logic of the work from that of society,” Adorno wrote. “The relentless unity of the culture industry bears witness to the emergent unity of politics. The concept of a genuine style becomes transparent in the culture industry as the aesthetic equivalent of power.”

TikTok is the next technological step of the Culture Industry. In creating a platform that awards creators with clout for their ability to generate attention for the app, Beijing ByteDance has injected a perverse, personal power politics into the very nature of art.

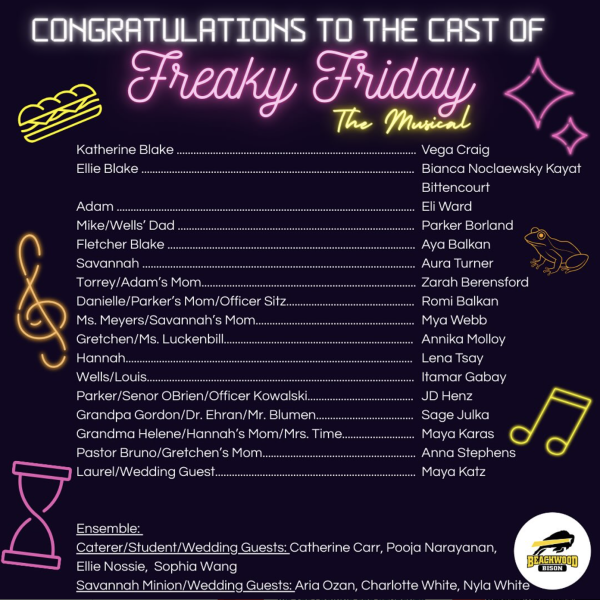

TikTok has embraced and subsequently sanitized various works of art, most notably nerdy cult musicals like Heathers and Beetlejuice, into shallow tools of the aforementioned struggle for clout.

Part 4: Ayo, conclusion check!

It is necessary we acknowledge TikTok as important, no matter the assertions we make about it. For better or for worse, this world of VSCO girls and e-boys is something that came up at a very formative time for many of us. It is not unlikely that TikTok, or the wider internet culture that it amplifies, will have as much of an influence on our generation as Rock and Roll had on previous generations.

Our cultural trajectory on social media mirrors that of our history as a species. The utility of apps like Vine (TikTok’s short-lived predecessor) and TikTok in a world dominated by more traditional sites like YouTube and Twitter is the idea that anyone can become a large creator, independent of budget. This is not unlike what interlopers and bankers experienced at the opening of the Atlantic, when the old landed gentry was transformed into a new aristocracy of wealth.

Social media differs from real life in a key respect: the means of production are forever in the hands of the very companies that supply the space of discourse. We cannot band together, and with our collective clout seize the means of production from Beijing ByteDance, because our presence on the platform is dictated by our ability to generate profit for them.

This is, of course, what the lumpenproletariat genuinely believe—that they are nothing without the bourgeoisie, that class structure is as much a part of the world as the source code of TikTok is a part of the app. And if gen-z is to be the generation to go through with the Marxist vision, we may have to first realize that life is not TikTok. Life is prime for revolution.

Alice Soprunova (she/her) began writing for the Beachcomber in 2019. She covers stories pertaining to issues of social justice inside and outside BHS....

gang of 4 • Jan 12, 2021 at 3:52 PM

just watched a compilation of the most successful tiktok videos, and the vast majority of them feature bourgeois people in mansions, private pools, etc

Dani • Oct 16, 2019 at 10:47 PM

I enjoyed this essay, Peter, thanks for sharing your analysis. Are you familiar with the Means TV project? I’d be interested to know your thoughts.

https://www.means.media/