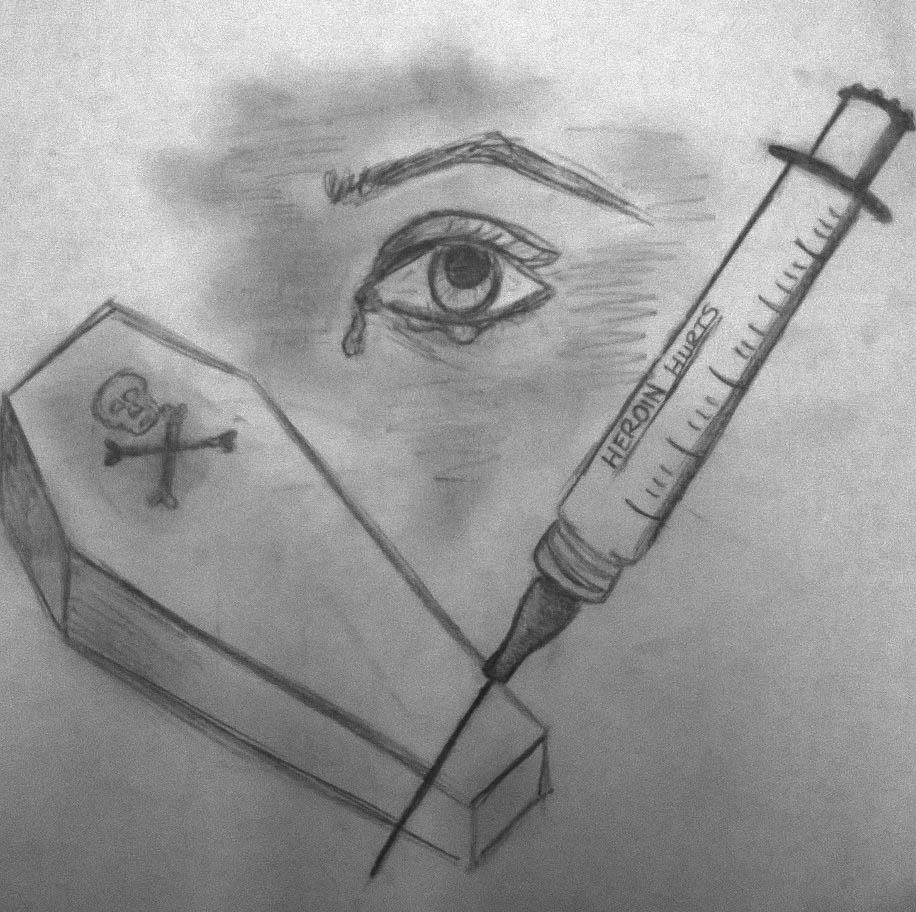

Heroin Epidemic Hits Cuyahoga County

84 residents of Cuyahoga County were murdered in 2013. Heroin killed 195 residents, and four times as many people died from heroin in 2012 than in 2007.

The Cuyahoga County Medical Examiner’s office confirms that contrary to stereotypes, this is not just an inner-city problem: approximately 50% of those 195 deaths were in the suburbs. 85.64% of the total heroin deaths in the county were of whites.

“Nobody ever takes a drug and says ‘I’m gonna become a pothead,’ or ‘I’m gonna become an addict,’” said Chris Ruma-Cullen, Social Advocates for Youth (SAY) Director at Bellefaire JCB, “but there are lots of alcoholics and addicts and potheads. Nobody sets out to do that, but a lot of people end up that way.”

The City of Beachwood made four arrests directly tied to heroin in 2013. However, many property crimes and shoplifting sprees were also related to heroin.

“When you talk about our jail population, a significant portion of the shoplifters, for example, are heroin addicts, or are addicted to other types of drugs,” said former Beachwood Police Chief Mark Sechrist, interviewed prior to his recent resignation.

“Everything from robberies to property crime, to people stripping copper….to people stealing a GPS or an iPod out of car. A lot of the property crime seen throughout the community is tied to heroin abuse,” said Community and Public Affairs Director Mike Tobin, who works with the US Attorney of the Northern District of Ohio.

Sechrist doesn’t believe the problem is any worse in Beachwood than in any of the surrounding cities.

“It’s across all the suburbs,” he said. “I don’t think anybody could say one suburb has more or less of a problem than any other suburb, so a bigger city is going to have more cases. Based on population, Beachwood’s problem is no bigger or smaller than anyone else’s.”

The Beginning of an Addiction

Many heroin users don’t even set out to do illegal drugs, rather they start by using legitimately-prescribed medicine for a real medical issue, such as a recovery post surgery.

“A person graduates to heroin. It can start with a legitimate prescription for painkillers after knee surgery or after back surgery,” BHS SAY counselor Ronna Posta said.

Doctors might prescribe far more pills than are strictly necessary.

“It’s sort of a cultural or societal belief that the first thing we do is reach for a pill when we are in pain,” Ruma-Cullen said.

Drug abuse counselors blame highly-marketed pain medication for opening the gateway to opiate addiction.

“[People taking medicines become] addicted to the feeling it causes,” Posta said. “It relaxes them, it does soothe pain. It’s not that they’re getting really high; it’s not like cocaine. They feel a sense of calm.”

Complications From the Addiction

Further problems arise when the prescription runs out.

“It would appear that the addiction to prescription pain pills has led people to switch from pain pills to heroin because apparently the pain pills are more expensive than street heroin,” Sechrist explained.

Once a heroin user is addicted, he or she begins to use it not to get high, but to alleviate the pain that comes from withdrawal. This feels like an especially horrible flu. An addict will do anything to get heroin, which is another negative consequence of the drug, besides its physical effects.

“They may lie, they may steal, they may disappear for periods of time, they may not be taking care of their physical health or mental health,” Posta said, noting that everything else, including jobs and family, can fall to the wayside. All that matters is the drug.

Heroin dealers and addicts have also found subtle ways of getting the drug. While at a party, some people will search the medicine cabinets at the house for opiate medicines, painkillers, or anything that will satisfy their cravings.

“There have been reports that during open houses, ‘professional drug seekers’ go…with the intent that one buddy [will talk] to the realtor, while the other is going through bathrooms and other drawers looking for meds,” Posta said. She stressed that while having service people come over or even letting visitors use the bathroom, it is crucial to hide medicines because they could end up being a source of someone else’s addiction.

Stopping the Problem

Because a full-fledged heroin addiction often starts out innocently with a legitimate prescription to pain killers, addictions can be difficult to prevent. However, the local community is working to combat the problem from all facets.

“[The US Attorney’s office], along with many other partners–Judge Astrab, Judge Matia, the County Sheriff’s office, and the Cleveland Police–have all been involved with prevention programs in the schools,” Tobin said. “[The] head of our drug unit, Joe Pinjuh, often speaks to schools. It’s a big part of what we’re trying to do.”

Prevention is not 100% effective, however. That’s where law enforcement comes in.

“We do our best to arrest dealers and shut down supply, but it takes more than law enforcement to shut down the demand,” Sechrist said.

In Feb., Mexican officials arrested Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman, head of the Sinaloa Cartel, which supplied a large portion of drugs to Northeast Ohio, according to news reports.

According to Tobin, this was a win for law enforcement, but it will not solve the smuggling problem.

“I don’t think we should overstate the impact,” Tobin said. “He led the multi-billion dollar national corporation. It would be foolish to think it won’t continue to operate, or other cartels won’t step in and fill their place.”

Two months after Guzman’s arrest, the Sinaloa Cartel continues to operate.

Treatment for a Disease

However, drug treatment professionals believe the dealers, not the addicts, should be viewed as criminals.

“It’s a disease,” Ruma-Cullen said of the addiction. “They get trapped in the cycle [so] that it’s not so much about the pleasure; it’s basically that they have an illness, and it’s [about] chasing the high. After a while, it wasn’t about having fun; it was about surviving and staying alive and going through the awful process of detoxing.”

“[The US Attorney’s office] is working with policy makers and lawmakers to get more beds available [in rehab, and to] change rules that make it easier to get people in treatment,” Tobin said.

Ruma-Cullen believes putting someone with a disease in jail won’t cure the disease. In fact, an addict is much more likely to overdose after being released from jail or even rehab. If their tolerance has been reduced during their time away from the drug and they take the same dosage they used to, it could be deadly.

“Nobody is looking to lock up everyone who uses heroin, but for the traffickers who are making millions off it, I think prison is the appropriate place for them,” Tobin said.

Rehab

Rehab is a long and often daunting process. “First thing is, helping them to try to recognize how it has affected the rest of their life,” Posta said.

After this, patients need either an in-patient residential program which includes both group and individual therapy, as well as education about the effects of drugs, or an intensive outpatient program. Patients are also frequently put on drugs such as methodone or suboxone while in rehab, which are both non-addictive, synthetic narcotics that help control cravings. This helps rewire the brain not to need the drug to which the patient was previously addicted. The goal of such programs is to replace drug use with healthier habits, which can be combined with therapy and 12-step meetings. 12-step meetings are led by recovering addicts, rather than professionals, and aim to inspire current addicts through others’ stories of recovery.

The next step, said Posta, is a referral to a halfway house–a place where patients live with other recovering addicts and a therapist. Halfway houses are less like rehab, and more of a place to get treatment and counseling while still interacting with the community. The most crucial part is that patients don’t relapse.

“If we can do a really good job of prevention, then we don’t have to worry about incarceration and treatment,” Ruma-Cullen said. “My hope is to get the word out there and educate young people that this is a danger, that this is a risk and help them find other ways to cope with problems.”

Cynthia Dettelbach • Apr 25, 2014 at 4:00 PM

Excellent article! Well-researched, clearly written and organized, and very interesting and informative! Way to go!!

Naomi • Apr 26, 2014 at 12:53 PM

Thank you, Cindy!